The Explorers

Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron Lahontan 1684-1689

Poverty drove Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, the third Baron Lahontan, towards an ultimately unremarkable career in the military. However his talents as a writer did bring him fame. Born on June 9, 1666 in La Hontan, in the historical province of Béarn, he was the son of Jeanne-Françoise Le Fascheux de Couttes and Isaac de Lom d’Arce. The family was left almost destitute by his father’s death, their lands ripe for takeover by those coveting their home. During his decade in New France, the situation continued to worry the young baron: that he would never be able to reclaim the complete control of his estate.

Route

Introduction to a new land

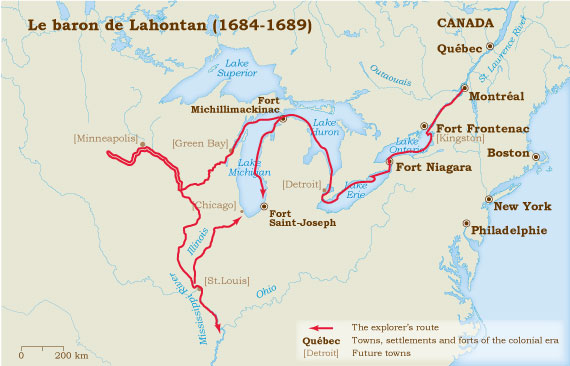

Baron Lahontan is one of the 200 soldiers sent by Louis XIV to help New France defeat the Great Lakes Iroquois. Landing in Québec on November 8, 1683, he spends the winter on the Beaupré shore. He begins his career as an observer, writer and ethnographer. In his second letter written from Beaupré on May 2, 1684, he writes: “In truth, the peasants here live much more comfortably than do many gentlemen in France. When I say peasants, I am in error. One must say habitants, since here, the word peasant is no more welcome than it is in Spain […]“. Later that month, Lahontan leaves for Ville-Marie. En route, he stops at île d’Orléans, Québec, Sillery, Sault-de-la-Chaudière, Lorette and Trois-Rivières.

First journey to the land of the Iroquois

On June 22 or 23, 1684, Lahontan leaves Montréal with a scouting party. They cross the rapids at Lachine, Cascades, Cèdres and Long-Sault and then follow the river up to Fort Frontenac (Cataraqui or Kingston), on Lake Ontario. Governor Lefebvre de La Barre, who wants to dictate the conditions for peace to the Five Nations, joins them in August. He is accompanied by more than 1200 soldiers, local militia and allied Amerindians.

Meanwhile, around Niagara, the fevers have claimed 80 people and affected many of the men. The Governor’s army soon begins to look like a “hospital on the move”. The expedition only gives the colony the illusion of peace while earning the scorn of the Iroquois who refuse to co-operate with some of the tribes traditionally allied with the French. Lahontan returns to Ville-Marie, disappointed to realize that the administrators, from the highest ranking to the lowest, are only interested in making money from the fur trade and could not care less about the Amerindians.

Second journey to the land of the Iroquois

In March 1685, Lahontan is an officer at Fort Chambly. Then, at the end of September, a month after de La Barre was replaced by Jacques-René de Brisay, the Marquis of Denonville, the Baron settles in Boucherville, where he stays until June 1687. The demands of his position are light so he is free to spend his time as he pleases. He travels to Lake Champlain, hunts game, both feathered and furred, fishes in the many streams and learns Algonquin.

In June 1687, he is among the 1600 men who accompany Denonville in a raid against the Iroquois. “Why are we bothering them?”, he writes in a letter dated June 8, “They have given us no cause to attack them.” He follows the army to Fort Frontenac and Niagara where the troops build a fort which is put under the command of the chevalier Pierre de Troyes.

Commander of Fort Saint-Joseph

Near the end of July, shortly before he returns to the colony, Denonville hands over the command to Lahontan of Fort Saint-Joseph (Detroit), which was founded by Daniel Greysolon Dulhut at the mouth of the strait that joins Lake Erie and Lake Huron. Although he had planned on returning to France, the Baron agrees to stay. He leaves Fort Frontenac on August 3 with Dulhut and about a hundred men. The next day, they start the portage around Niagara Falls, “that terrifying cataract”. They then cross Lake Erie, go up the Detroit River to Lake Saint Clair which they reach on September 8. Six days later, they arrive at Fort Saint-Joseph, at the entrance to Lake Huron.

Winter is hard for the detachment. It is short of supplies and is worried about an attack by the Iroquois. Lahontan leaves the fort on April 1, 1688, hoping to find supplies at Michillimakinac, northwest of Lake Huron. Later that same spring, he travels as far as the rapids at Sainte-Marie, where they enter Lake Superior. Back in Michillimakinac, he encounters the survivors of Cavelier de La Salle’s expedition who hide from him the fact that La Salle had been murdered on March 19, 1687 “We think he must be dead since he did not come out to greet us in person”, writes Lahontan.

On August 24, 1688, he is back at Fort Saint-Joseph where he learns that scurvy has been ravaging Fort Niagara and that the commander, the chevalier Pierre de Troyes, had died from fever. Having on hand only enough supplies for two months and “having received neither orders nor succor […] we razed the fort on the twenty-seventh”. The commander and his soldiers leave for Michillimakinac that same day.

The imaginary journey

Nothing that is known about the Baron de La Hontan explains why he is suddenly overcome by a desire to explore the Great Lakes “I am about to start another journey since I cannot stand to mope around here all winter”, he explains in his 15th letter. Accompanied by four or five “good Ottawa hunters” and part of his detachment, he leaves Michillimakinac on September 24, 1688 for a journey which may never have really happened.

After reaching Lake Michigan from the north, he enters the baie des Puants (Green Bay). South of the bay, he canoes down Fox River and portages to the Wisconsin River. Once there, he continues to head west until he reaches the Mississippi River. The convoy of six canoes follows the river until they reach the mysterious “Long” river which he says he began exploring starting on November 2nd.

Was he looking for a passage to the western sea or to Hudson’s Bay? On March 2, 1689, Lahontan returns to Michillimakinac by way of the Mississippi, the Ohio and Illinois Rivers, the Chicagou (Chicago) portage and Lake Michigan. By July 9, he was back in the colony. Even though he could have benefitted both financially and career-wise, for some reason, he speaks to no one about his discovery of the “Long” River (which may be the Saint-Pierre River). He never describes to anyone the fabulous tribes that he met: Essanapes, Gnacsitares, Moozimlek, Nadouessioux and the Panimobas and, after him, no one else ever saw the “Long” River…

Exile and fame

On October 1689, Louis de Buade de Frontenac became governor of New France for a second time. In November 1690, a month after William Phips is routed at Québec, Lahontan finally leaves for France. A year later, after his return to Québec, he becomes part of the governor’s inner circle. Frontenac is so impressed by him that he offers the Baron a very advantageous marriage to his god-daughter. Preferring his freedom, Lahontan turns down this generous offer. Having a lot of free time on his hands, he designs a plan for a Great Lakes navigation system and recommends the construction of three forts at strategic locations on those lakes. Frontenac supports the idea and sends Lahontan to France to submit the proposal to the Minister for the Colonies.

Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce de La Hontan sails from Québec on July 27, 1692 never to return . A layover takes him to Placentia where he helps with the defense of the fort. In France, there is no interest in his plan. However, his courage is rewarded by an appointment as Lieutenant- Governor of Placentia, which displeases the Governor, Jacques-François Monbeton de Brouillan.

Brouillan keeps careful track of everything Lahontan says and does, and prepares a sufficiently damning case that the 26-year old Baron decides to disappear: “the possibility of a stay in the Bastille worried me so much that, after careful consideration of the unpleasant situation I found myself in, I decided to board the last and only small ship going to France”.

After leaving Placentia on December 14, 1693, Lahontan took refuge in Holland. Using the copious notes and the diary he kept during his stay in New France, in 1703, he began publishing works that made him famous. When he apparently died between 1710 and 1715, he was one of the most respected and widely-read writers in Europe.