The Explorers

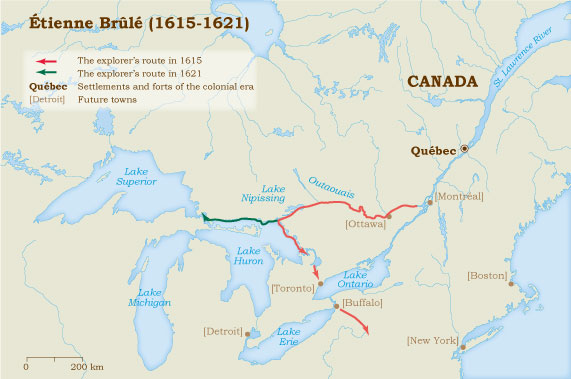

Étienne Brûlé 1615-1621

The life story of Étienne (Stephen) Brûlé, interpreter and explorer, contains an element of mystery. He was born about 1591, at Champigny-sur-Marne near Paris. He is believed to have made the voyage to Quebec in the company of Samuel de Champlain in 1608. It was the decisive move in his career. He was to become an interpreter, or dragoman (truchement in French), between the French and their Amerindian allies. But he was above all a pathfinder and a scout. He played an essential role in the first documented journeys of exploration in New France by going ahead of Samuel de Champlain, Gabriel Sagard, Jean Nicolet, Nicolas Perrot and others of their ilk along the route to the Great Lakes. He appears to have been the first European to set eyes on the Ottawa Valley, Georgian Bay, Pennsylvania and four of the Great Lakes, and to give at least an oral description of them.

Route

Getting to Know the Country and its Peoples

In 1610, Champlain, the founder of the colony of New France, had already explored the Richelieu River as far as Lake Champlain. He now turned his attention further inland, aware that any discovery must start west of Sault St. Louis (the Lachine Rapids). At the end of June that year, he entrusted Étienne Brûlé with the task of finding a route:

“I had with me a youth who had already spent two winters at Quebec and wanted to go among the Algoumequins [Algonquins] to master their language … learn about their country, see the great lake, take note of the rivers and the peoples living along them; and discover any mines, along with the most curious things about those places and peoples, so that we might, upon his return, be informed truthfully about them.”

On the thirteenth of June, 1611, Champlain succeeded in navigating the Lachine Rapids. He stated that “no other Christian other than him, my lad” had previously made the attempt. Either below or above the rapids he met up with Brûlé:

“I saw too my lad come dressed in the manner of the savages, mightily pleased with the treatment which the savages had accorded him, according to the custom of their country, and he related to me all that he had seen during his winter among them and had learned from said savages. … My lad … had learned their language very well.”

Deep into Huronia

Brûlé left again immediately, taking the direction of the country of the Hurons. Their territory was located on the peninsula between Lake Ontario and Lake Huron. To reach it he must have travelled up the Ottawa and the Mattawa rivers, then crossed Lake Nipissing, and followed French River down to Georgian Bay.

On the first of August, 1615, Champlain “discovered” Lake Huron, where he met his intrepid interpreter and gave him permission to go among the Andastes, to the south of the Iroquois country, “since it was his own desire to do so and by that means he might see their country and come to know well the peoples living there.”

And so, on the eighth of September, 1615, Brûlé departed from Lake Simcoe with his Huron guides. He made his way to the site of the present-day city of Buffalo, at the junction of Lakes Erie and Ontario. Then he went on as far as the Susquehanna River “which empties [into the sea] on the Florida side [of the continent] where there is a multitude of powerful and warlike nations.”

In the spring of 1616, our explorer left the Andastes country and made his way northwards again, only to be taken prisoner by the Iroquois. According to his own account, he was tortured and his life was threatened. He literally saved his skin by bluffing, won his captors’ respect, and held himself out to be an influential negotiator, even promising “to bring them into agreement with the French, & their foes, & to make them swear friendship to one another.”

In July, 1618, Brûlé arrived back in the colony after an absence of thirty-four months. By his own account he was the first European to explore what is now the State of Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania and Lake Superior

By 1618, Brûlé wanted to press forward to Lake Superior. Champlain commissioned him to accomplish his desire, “which he promised me to persist in, and to carry it out in a short space of time, by God’s grace, and to conduct me thither.”

From then until 1621, Brûlé made a winding journey that led him to Sault Ste. Marie at the junction of Lakes Superior and Huron. Here is the evidence from the writings of the Récollet (Franciscan) missionary Gabriel Sagard: “The interpreter Bruslé [sic] with several Savages assured us that beyond the Freshwater Sea [Lake Huron] there was another very large lake which empties into it by a waterfall, which has been called ‘Saut de Gaston’ [Gaston Falls, i.e., Sault Ste. Marie].”

Betrayal

It was Gabriel Sagard who, in 1624, discredited Brûlé in Champlain’s eyes. The Récollet friar denounced the wandering adventurer’s loose morals, and disclosed moreover that Brûlé was playing a double game: he was working at the same time for the administration of New France and for the fur merchants, who were opponents of Champlain.

Brûlé’s reputation was blackened for ever in 1629. Champlain had capitulated to the Kirke brothers, and most of the French in the colony had returned to their homeland. At Tadoussac, Brûlé and his fellow interpreter Nicolas Marsolet admitted it was their intention to remain in New France. “We have been taken by force,” was their excuse to Champlain, “and we know very well that if we were held in France we would be hung.”

Brûlé was killed by the Hurons while the colony was still under the English. The news reached Champlain when he returned to Quebec in 1633.