-

- Introduction

- Colonies and Empires

- The Explorers

- Jacques Cartier 1534-1542

- Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616

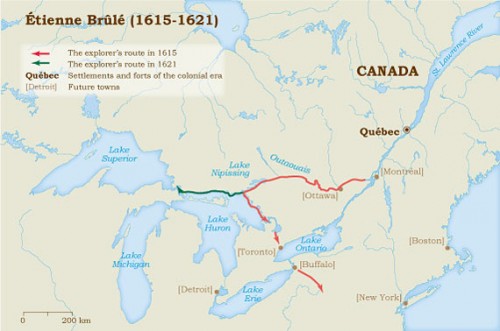

- Étienne Brûlé 1615-1621

- Jean Nicollet 1634

- Jean de Quen 1647

- Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers 1654-1660

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson 1659-1660

- Nicolas Perrot 1665-1689

- René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle 1670-1687

- Charles Albanel 1672

- Jacques Marquette 1673

- Louis Jolliet 1673-1694

- Louis Hennepin 1678-1680

- Daniel Greysolon Dulhut 1678-1679

- Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron Lahontan 1684-1689

- Pierre de Troyes 1686

- Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville 1686-1702

- Antoine Laumet dit de Lamothe Cadillac 1694-1701

- Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye 1732-1739

- Economic Activities

- Population

- Daily Life

- Heritage

- Useful links

- Credits

Population

Pays d’en Haut and Louisiana

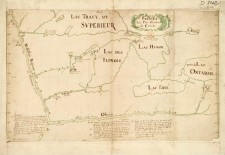

The “Pays d’en Haut” or Upper Country: under the French Regime, this name described the basin of the Great Lakes, upriver from the St. Lawrence, where fur traders, missionaries, and military men ventured beginning in the early seventeenth century. Beyond the 1660s, their visits became more regular. Outposts multiplied, in several cases giving birth to flourishing settlements. That of Detroit, between Lakes Erie and Huron, became something of a capital for the region.

Thanks to the goodwill of the Aboriginal peoples who represented a clear majority in the continent’s interior, the French soon took the stride between the Great Lakes basin and the Mississippi valley. In 1682, the explorer Robert Cavelier de La Salle reached the mouth of this great river and claimed his discoveries on behalf of the French king. Thus, in honour of Louis XIV, this immense territory received the name of “Louisiane”, Louisiana. During the following century, Louisiana would in turn become a settler colony – less populous than Canada, to be sure, but no less essential to New France as a whole.

In the “Pays des Illinois” or Illinois Country, named after a powerful Aboriginal confederacy and centred on the southeast of the state which still bears its name, the French drew profit from the river network and the richness of the soil to develop a thriving agriculture. This territory, which passed from the authority of Canadian officials to that of their counterparts in Louisiana in 1717, quickly became a vital breadbasket for all of Lower Louisiana. These are the colonial space, rather underappreciated in comparison with the St. Lawrence valley, that readers will discover in this upcoming article.

The Illinois Country (show)

Although explorers, missionaries, and fur traders had travelled through the middle Mississippi Valley since the 1630s, the French did not begin to settle there in earnest until the turn of the eighteenth century. They first established missions to the Native peoples, then built forts to stake France’s claim to the territory and provide a measure of protection to colonists. Soon thereafter, the French established various kinds of communities along both sides of the Mississippi River, in an area known as the Illinois Country, which encompassed primarily the present states of Illinois and Missouri. Following the pattern of New France and lower Louisiana, French colonies in the Illinois Country tied their settlements to water routes, which facilitated intensive interaction among the thin scattering of French colonists in North America. This landscape is characterized by river bluffs interspersed with wide expanses of floodplain, intersected by several other large rivers, such as the Missouri, the Illinois, the Kaskaskia, and the Ohio. Originally part of the province of Canada, after 1717, it was considered to be part of Louisiana. This dual identity was reflected in the cultural landscape and social composition of the Illinois Country – part canadien, part louisiane.

The Settlements (show)

The earliest colonial settlements were missions. The mission at Cahokia began in 1699 and that at Kaskaskia began in 1703, named after the Native groups at each location. Before Europeans arrived, these Native groups were agriculturalists, settled into villages in the river floodplain east of the Mississippi; their ancestors had been farming the same floodplain for at least 700 years. Europeans, in general, categorized agricultural Native groups as more “civilized” than hunting and gathering groups, since European definitions of civilization necessarily included agriculture as a component. French missionaries, then, often located their missions near the villages of agricultural Native groups where, not coincidentally, they had more secure access to “acceptable” foods than they would have had in more remote locations.

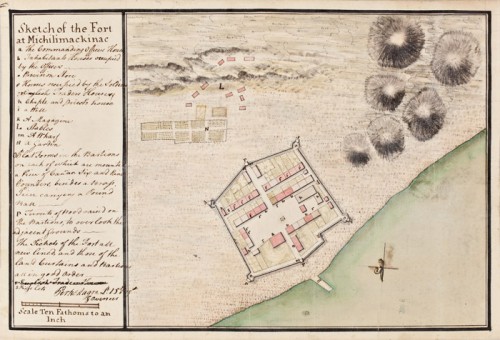

With these initial contacts established with Native groups, the French placed forts at strategic locations, often near the missions. However, it was not until the 1710s and 1720s that France made a concerted effort to establish forts, trading posts, and settlements in the Illinois Country. In 1717 John Law and his Compagnie de l’Occident were granted a royal charter which gave them the monopoly over all trade in the colony of Louisiane, including, from that time on, the Illinois Country. This marked the beginning of more intensive French colonial activity in the entire arc from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. In the second and third decades of the eighteenth century, numerous Vauban-style fortifications, often preceded by missions, were established (or re-established) in the western Great Lakes and the Mississippi Valley: for example, Fort Michilimackinac, Fort Ouiatenon, Arkansas Post, Fort Toulouse, and Fort St. Jean Baptiste.

Thus, as it was establishing forts elsewhere in the colonies, in 1718, France secured the middle Mississippi Valley by beginning construction of Fort de Chartres. The first fort, of wood, was finished in 1721; the third (or possibly the fourth) fort was built of stone in the 1750s, and was the only stone fortification constructed by the French in the entire Mississippi Valley. It occupied a strategic position at the very center of the Valley, at the intersection of Canada and Louisiana, and was clearly France’s bulwark along its western boundary.

French settlement did not proceed gradually from one end of the Mississippi Valley to the other. These initial settlements occurred at about the same time. John Law’s charter provided for the transportation of colonists up the Mississippi River to Arkansas and the Illinois Country, and convoys began bringing settlers, particularly farmers and artisans, up the river in 1718. French villages were established initially at Cahokia and Kaskaskia, surrounding the forts and missions there, and the missions very quickly became parish churches. Soon, colonists from New France and France settled in the villages as well. Population growth resulted in expansion into new settlements at St. Philippe, Prairie du Rocher, Peoria, and, eventually across the Mississippi on its west bank, at Ste. Genevieve (c. 1750) and later St. Louis (1764).

The meandering Mississippi River has washed away some of these settlements, such as St. Philippe and Kaskaskia on the eastern shore and much of the original town of Ste. Genevieve on the western shore. River movement and bank erosion was exacerbated by the overexploitation of forests along its banks, caused by the great demand for wood to power steamboats in the nineteenth century. In spite of this, archaeologists have been able to study several of these French villages, such as Prairie du Rocher, Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Ste. Genevieve, and, along with historians, are beginning to provide a picture of daily life in the Illinois Country.

The Regional Economy (show)

Although agriculture was key to the economy of the region, these settlements depended, from the beginning, on the exploitation of other resources as well: lead, salt, and furs. Individuals often were involved in more than one of these endeavors and the Illinois Country economy could not function successfully without all four elements. Settlement patterns differed according to the resource to be extracted; people moved between the settlements as the need required.

Agriculture

French colonial agriculture in the Illinois Country centered on production of wheat and pork. In fact, this “breadbasket” was responsible for most of the wheat grown in France’s colonies, and was depended upon for daily bread (literally) up and down the valley, especially in New Orleans. Economic records have revealed a brisk traffic in foodstuffs, especially wheat flour, corn, pork, bear oil, bison tongues, and salt, between the Illinois Country and New Orleans. Regular shipments of these items moved downriver, followed by return convoys loaded with manufactured items from France and other French colonies, obtained from merchants in New Orleans.

Most of the agricultural villages in the Illinois Country utilized a tripartite settlement pattern of village, fields, and common woodlands. The villages were laid out in a grid pattern of streets and lots. Individual town lots were surrounded by palisade fences, inside which were the main house, slave quarters, barns and other outbuildings, gardens, and orchards. Agricultural fields were located outside of town and were laid out in long lots, following traditional French practice. The long lots stretched from the river bank to the bluffs and were individually owned. Each owner was responsible for keeping the fence posts at the end of his/her lot in good condition, so that domestic animals could not get into the fields and destroy the crops. The “common” areas were on the wooded bluff slopes, where everyone had access to firewood or pasture, although many domestic animals freely roamed the streets of the towns as well.

Lead

Lead was a resource that all colonial powers sought in North America. It was critical for everyday use by soldier and civilian alike, for defense and for hunting. Lead mining, lead shot production, and bulk lead production were profitable businesses engaged in by successful French colonial elites. They owned the mines and often employed their own and others’ enslaved Africans to work them. On the western side of the Mississippi, about 30 miles west of Ste. Genevieve, were the lead-mining settlements. Lead was found in very shallow deposits, so the recovery resembled surface mining more than it did deep pit mining. French colonists settled very near the mining areas, often along a creek or stream, but not in a regularized pattern. The placement of dwellings was dictated instead by the location of the lead deposits.

Salt

Salt was an important resource, used not only for preservation of meats and for seasoning foods, but also for tanning and preserving bison hides and furs. One of the largest salt sources in the Illinois Country was La Saline, a large creek fed by salt springs, which flowed into the Mississippi on the west bank, about six miles south of Ste. Genevieve. French colonists had been coming across the river to utilize this source since the late 1680s, and Native Americans had used it since at least AD 1000. After Ste. Genevieve was established, however, the French intensified their salt production along La Saline, building large stone firepits to boil huge iron kettles of salt water until the water was evaporated. A few French elites owned the rights to the salt production, and they employed other colonists, and used African slaves, to make the salt. Not as haphazardly placed as the lead-mining settlements, the houses and fenced lots at La Saline nonetheless followed the shores of the stream, keeping to higher elevations when possible to avoid seasonal floods.

Fur trading

The fourth element in the Illinois Country economy was fur trading. While coureurs des bois operated as independent trappers and traders, other French colonists worked in the fur trade for local or other merchants, often on a part-time basis (usually during the winter, when they were not engaged in agriculture). In some cases, French colonists trapped fur-bearing animals and processed the furs themselves. In other cases, French colonists went directly to Native groups and bartered with them for the furs they had produced. In still other cases, Native groups or individuals brought furs to the French villages, to trade for goods there. By whatever means they were obtained, it is clear that furs were a major component of the local economy until the mid-nineteenth century. Local merchants had stacks of furs that they used in barter transactions and, indeed, furs, hides, and lead were nearly the only circulating mediums of exchange in the region.

French colonists in the Illinois Country depended on agriculture, lead mining, salt production, and fur trading to make a living. They often combined two or more of these occupations, moving between locations as necessary. Individuals also engaged in artisanal production for their own use or as a cottage industry, seen in the evidence of lead shot production found archaeologically behind a French house in Ste. Genevieve. Whether or not they were engaged personally in the fur trade or in lead production, however, everyone in the Illinois Country villages used those items for exchange in what was essentially a barter economy until the middle of the nineteenth century.

Native Americans and African Americans (show)

Native Americans, Africans, and African Americans lived in the Illinois Country, as free and enslaved individuals. French colonists interacted with these groups in a variety of ways. Although enslaved individuals of all of these groups performed agricultural labor, they were employed as well in a wide range of activities, including salt production, lead mining, river transportation, fur trapping, and household production. Free Native Americans and African Americans had a different status vis-à-vis French settlers, which also changed through time.

Some French Canadian men married Native women in the Illinois Country, both formally and informally, and therefore had kinship ties to Native groups. Some Native peoples were enslaved, others settled in and around French villages for various periods of time, and others visited towns only occasionally to trade. Up until their forced removal by the U.S. government in the 1830s, Shawnees, Peorias, Delawares, and Kickapoos lived on the outskirts of Ste. Genevieve as well as in the town itself, and for the most part maintained peaceful relations with the Euroamerican residents.

Archaeological evidence from the Janis town lot in Ste. Genevieve also suggests that French households or businesses (a tavern, in this case) limited the movements of free Native Americans to the public portion of the property, nearest the street. This is where archaeologists found the highest concentrations of glass seed beads and lead shot, two important items traded to Native peoples for furs. The palisade fences around town lots seem to have effectively blocked Native Americans from entering other portions of the property.

Historical records indicate that there was perhaps greater freedom of movement for enslaved Native Americans and African Americans in the French villages of the Illinois Country than there was for free Native Americans. Enslaved individuals not only lived and worked in the yard of the town lot and in the main house, but also worked in the agricultural fields, mines, rivers, and streams outside of town, ran errands and made purchases for their owners, and visited family and friends in the town. Another distinctive aspect of French towns in the Mississippi Valley was the presence of sizable numbers of free people of color. Much larger communities of free people of color existed in Lower Louisiana, but their presence in Upper Louisiana, or the Illinois Country, was notable and long-lasting.

The Example of the Ribault Family

By at least 1820, French nobleman John Ribault, probably in his thirties, had arrived in Ste. Genevieve as a refugee fleeing the slave revolt in Saint Domingue. Quickly becoming one of the leading citizens of the town, he served as a witness at marriages of the town’s elite and as a court-appointed juror during the 1830s and 1840s. Sometime in the 1820s, he began a relationship with an African American woman named Clarise. She was also in her thirties and at the time was enslaved by Ribault’s neighbor, François Janis. Although still enslaved in 1833, when Janis’ heirs divided his property, Clarise, her daughter Thérèse, and her mulatto son John, were, at least by 1835, free persons of color, probably living just down the road from the Janis family in the house that Clarise purchased in 1840. Although interracial marriage was illegal in Missouri in the 1830s, her relationship with John Ribault continued until his death in 1849; he provided in his will an annual income for Clarise, her son John Ribault, and her granddaughter Clara, identifying the last two as free people of color. Clarise continued to live in the house until she died in the 1880s, residing with her son John and his children. This example has all of the earmarks of plaçage arrangements known for Lower Louisiana, between French men and free women of color; Clarise’s grandchildren, in the 1960s, identified themselves as quadroons, an appellation more commonly known in Lower Louisiana.

French Cultural Traditions in the Illinois Country (show)

Although thousands of miles separated the thinly scattered French colonists in North America, individuals and families maintained lasting business and kinship ties between New France (Canada), Louisiana, and France. In spite of this, however, French settlements in the western Great Lakes and Mississippi Valley operated more or less on their own, free from the closer administrative control that Paris maintained in eastern New France and Lower Louisiana. The Illinois Country most often included villages reminiscent of those in France, from which these settlers, their parents, or grandparents had originated. Often, then, the secular and religious hierarchies of the Old World were reproduced in the colonies, especially in the larger agricultural villages.

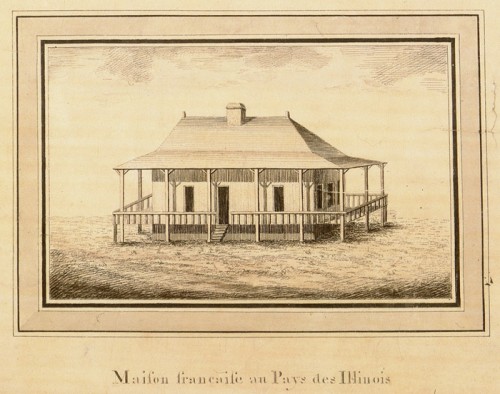

In some cases, such as at Ste. Genevieve, French cultural traditions persisted long after the end of French colonial control. After the French and Indian War, France’s former colonies were ceded to Britain and Spain. The Illinois Country thus became divided after the Conquest: lands to the east of the Mississippi River were ceded to Britain, and those to the west were ceded to Spain. Although under Spanish colonial rule after 1763 and including ever more Anglo-Americans, especially after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Ste. Genevieve remained overwhelmingly French in character and in population well into the 1830s. The post-Conquest French population in the region was comprised of Canadiens, people born in the Illinois Country, French from other colonies (especially Saint Domingue after 1791), and aristocrats fleeing the Revolution in France. Ste. Genevieve, Missouri, today contains more standing structures of French vernacular colombagearchitecture than anywhere else in North America, all of which were built between the 1780s and 1850, long after the end of the French regime. French cultural traditions persisted in language, religion, legal practices, and social hierarchy, as well as in the town plans and architecture visible to us today and archaeologically.

French house in Illinois Country, detail from the Ohio River map [Carte générale du cours de la rivière de l'Ohio…], ca. 1796, Victor Collot

An Example of Cultural Persistence

The Janis family gives us a good example of cultural persistence. Nicolas François Janis was born at Québec in 1720. His father, François Janis, was born in Champagne around 1676 and emigrated to Trois-Riverières, Canada, where he married Simone Brosseau in 1704. Nicolas and one of his brothers, François Eustache, were both engaged in fur trading between Montreal and the western Great Lakes in the late 1730s and early 1740s. By 1747, Nicolas was, himself, a successful merchant in Kaskaskia, in the Illinois Country, buying and selling land on both sides of the Mississippi River. In 1751, he married Marie Louise Thaumur dit LaSource, and they subsequently had nine children. Like most of the residents of Kaskaskia at the time, he lived in the town on the east side of the river and owned farm land in Le Grand Champ across the river, where the first town site of Ste. Geneveive grew up in the early 1750s.

Nicolas bought the property where his Ste. Genevieve house now stands in 1790 from Antoine Dufour. This property was in Nouvelle Ste. Genevieve, located on slightly higher ground than the original town to escape the floodwaters of the Mississippi River. Settlement in the new town began in the late 1780s and early 1790s, which happened to coincide with a larger migration of French-descended peoples from the east side to the west side of the Mississippi River. By this time, American settlers and governmental authority had become a presence to be reckoned with on the east side, and most settlers of French heritage chose to live in what was still Spanish territory across the river than to stay in Illinois under the Americans.

One of the consequences of this migration, primarily to Ste. Genevieve and St. Louis, was the Spanish government’s commission of a census, to document the unexpectedly large increase in population. On the 1791 census, Nicolas Janis is listed as a resident in Ste. Genevieve, with four white members of his household and ten African American slaves. He also possessed, at the time, greater than average quantities of wheat, corn, and tobacco, compared to the other residents. Through the marriages of their children, Nicolas and Marie-Louise became related to three of the most prominent families in Ste. Genevieve: Bolduc, Bauvais, and Bienvenu. Thus, these new residents to Ste. Genevieve had actually lived in the area for more than forty years, were a prominent family, and were situated well in Ste. Genevieve’s social hierarchy.

Nicolas, now about 70 years old and a widower, and his youngest son, François, built the new house (or rather, his slaves built it) in 1790-1791. Although the house incorporates an American-style gable-ended roof, it is otherwise of classic French vernacular style: vertical squared posts on a sill beam, resting on a stone wall which comprises the ground floor. Bousillage, which is clay mixed with wheat straw in this case, was packed in between the upright posts, and then the whole was whitewashed. The large overhanging porches added additional protection to this earthfast building.

In lower Louisiana, this form is known as a raised creole cottage, with the ground floor serving as storage or work space, and the raised first floor being the living area. There are multiple doors on the front, related to the combination of domicile and tavern under the same roof. The first floor rooms are arranged in a typically French vernacular plan, connected one to the other with no central hallway. After Nicolas’ death, his son François lived in the house with his own family until he died in 1832.

Nicolas Janis was wealthy enough to have built any kind of house he wanted, but nearly thirty years after French colonial rule ended, he chose to build a house that would be recognized as “French.” Similar choices were made by French-descended people up and down the Mississippi Valley until the mid-nineteenth century. A similar cultural persistence may be seen in dietary traditions, legal practices (particularly inheritance practices and marriage contracts), musical traditions, and religious and holiday celebrations.

Conclusion (show)

Although French-descended people in the Illinois Country certainly modified some of their customs as they adapted to physical and social environments that were very different from the ones they knew in France or Canada, they also held on to other customs, maintaining traditions and practices that were part of a shared French heritage. In spite of numerous changes in government and an influx of Anglo-American and German immigrants into the Illinois Country, French-descended people in small towns and villages there demonstrated a cultural persistence that lasted nearly a century after the Conquest.

Further Readings (show)

Belting, Natalia Maree. Kaskaskia Under the French Regime. Reprint of the 1948 edition. Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, 2003.

Edwards, Jay D. “Creole Architecture: A Comparative Analysis of Upper and Lower Louisiana and Saint Domingue.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 2006, 10(3): 241-271.

Ekberg, Carl J. French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times. University of Illinois Press, Urbana & Chicago, 1998.

Gitlin, Jay. The Bourgeois Frontier: French Towns, French Traders, and American Expansion. Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2010.

Havard, Gilles et Cécile Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique française, Paris, Flammarion, 2003.

Kimball Brown, Margaret, « La colonisation française de l’Illinois : une réévaluation », Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, vol. 39, no 4, printemps 1986, p. 583-591.

Lessard, Renald, Jacques Mathieu et Lina Gouger, « Peuplement colonisateur au Pays des Illinois », dans Philip Boucher et Serge Courville, dir., Proceedings of the Twelfth Meeting of thew French Colonial Historical Society, Ste Genevieve, Missouri. May 1986, Lanham, University Press of America, 1988, p. 57-68.

Mazrim, Robert. At Home in the Illinois Country: French Colonial Domestic Site Archaeology in the Midwest 1730-1800. Studies in Archaeology No. 9, Illinois State Archaeological Survey. University of Illinois, Urbana, 2011.

Schroeder, Walter A. Opening the Ozarks: A Historical Geography of Missouri’s Ste. Genevieve District, 1760-1830. University of Missouri Press, Columbia & London, 2002.

Vidal, Cécile, « Le Pays des Illinois, six villages français au cœur de l’Amérique du Nord, 1699-1765 », dans Thomas Wien, Cécile Vidal et Yves Frénette (éds.), De Québec à l’Amérique française. Histoire et mémoire. Textes choisis du deuxième colloque de la Commission franco-québécoise sur les lieux de mémoire communs, Québec, Presses de l’Université Laval, 2006, pp. 125-138.

Vidal, Cécile, « Présence française dans la vallée du Mississippi », Cap-aux-Diamants, Revue d’Histoire du Québec, n°62, 2000, p. 40-45.

Walthall, John A. (editor). French Colonial Archaeology: The Illinois Country and the Western Great Lakes. University of Illinois Press, Urbana & Chicago, 1991.

![Map of the New Discovery made by Jesuits in the year 1672 followed by Jesuit Jacques Marquette […] in the year 1673 | Cartes et plans, GE C-5014 RES, Bibliothèque nationale de France Map of the New Discovery made by Jesuits in the year 1672 followed by Jesuit Jacques Marquette […] in the year 1673](https://www.historymuseum.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/files/2012/04/New-France_4_5_Map-of-the-New-Discovery-made-by-Jesuits-in-the-year-1672-500x292.jpg)