-

- Introduction

- Colonies and Empires

- The Explorers

- Jacques Cartier 1534-1542

- Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616

- Étienne Brûlé 1615-1621

- Jean Nicollet 1634

- Jean de Quen 1647

- Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers 1654-1660

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson 1659-1660

- Nicolas Perrot 1665-1689

- René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle 1670-1687

- Charles Albanel 1672

- Jacques Marquette 1673

- Louis Jolliet 1673-1694

- Louis Hennepin 1678-1680

- Daniel Greysolon Dulhut 1678-1679

- Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron Lahontan 1684-1689

- Pierre de Troyes 1686

- Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville 1686-1702

- Antoine Laumet dit de Lamothe Cadillac 1694-1701

- Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye 1732-1739

- Economic Activities

- Population

- Daily Life

- Heritage

- Useful links

- Credits

Colonies and Empires

Founding Sites

Barren Northern Terra Nova or Enchanted Southern Islands?

France’s adventure in the Americas began in the 16th century, when King François I commissioned an Italian, Giovanni da Verrazano, to explore the coasts of the continent discovered by Christopher Colombus at the end of the previous century. For nearly 100 years, the French embarked on several endeavours to settle the continent of the Americas, which as Raymonde Litalien relates here.

After explaining what these explorers hoped to discover, the author draws a portrait of the various sites of French founding settlements in the Americas, from the first, short-lived colony of Charlesbourg-Royal (1541–1543), to the founding of Québec in 1608. She thereby reveals the astonishing destinies of communities that while often driven by very different motivations, nevertheless all wished to found a new country that would resemble yet diverge profoundly from their native land: a new France!

The story transports the reader from Acadia to the beaches of the bay of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where the French briefly tried to compete with Portuguese colonists, as well as to Florida, to Fort Caroline, a colony that met with a particularly tragic fate.

This fascinating era of the first attempts at settlement also saw the discovery of the Amerindians, the first encounters between Europeans and the peoples of the Americas, their early trading, and their first misunderstandings.

Rush for the New World (show)

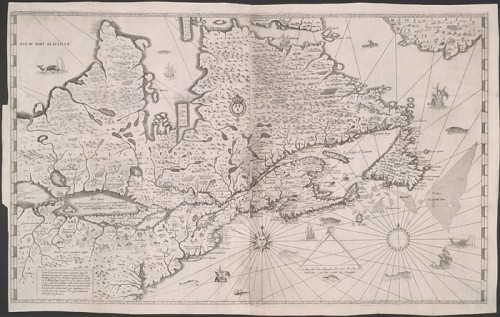

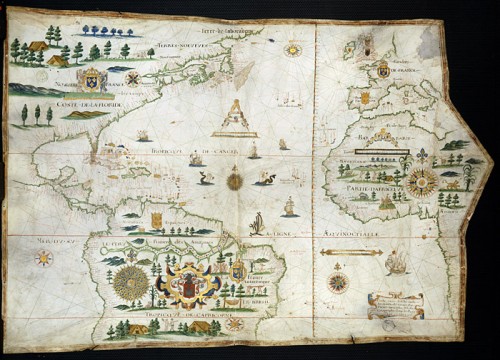

Seeking a western route to Asia, European navigators of the 16th century discovered territories whose dimensions, resources and populations were unfamiliar to them. In fact, mariners had stumbled across the two continents of the Americas. With steadfast determination, sovereigns sent explorers to survey these new lands and map them with a view to finding resources and founding settlements. However, the surveyed shorelines and the newly discovered lands were kept secret. All of the voyagers jealously preserved the observations they noted during their journeys. As a result, their discoveries would long be presented as an imaginary world, either through real ignorance or the desire to keep discoveries a secret and to sustain hope of finding even greater riches.

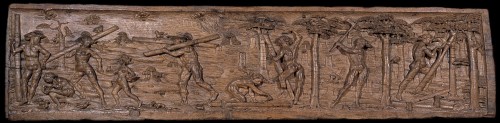

Capturing the Riches of the Americas

In France, private enterprise did not wait for any official mission to seek profits from new discoveries. From the early 16th century, Norman merchants regularly travelled to Brazil seeking dyewood used to make dye for the textile industry, and every year, Bretons fitted out ships for fishing off the coasts of Newfoundland. Both groups, venturing between these two hubs, located fine arable land in northern Florida. They were followed by sailors from all of France’s Atlantic and North Sea ports as soon as knowledge of the wealth of fish resources in northern waters spread. Another surprise awaited European voyagers, both in the southern and northern continents: it was already inhabited by people who had long lived there and had an extensive knowledge of the land and its resources. The Europeans would long hesitate to admit that they had not encountered Chinese people or Indians from India. The French and these native Americans quickly established trade relations, each securing from the other the commodities and services they could not find by other means. These preconditions greatly facilitated the founding of colonial settlements.

Where Might a New France be Established?

The objective in the medium term was to build a new France on the vast landmass of the Americas. New France was the name that Giovanni Verrazzano gave to the coast between Florida and Newfoundland which he sailed in 1524, on the first official expedition commissioned by King François I of France. Verrazano understood this continuous shore as nothing but another barrier between Europe and Asia. He also presumed that it concealed a continent whose dimensions were as yet unknown. From then on, all voyages of exploration to the Americas would seek a river or land route that would facilitate crossing the continent.

Surrounding “new” France were several rival colonies, established on southern islands and lands that appealed because of their riches and climate. France’s choice of settlement sites inevitably depended on the number and nature of its native inhabitants, competition from other European powers, and the nature (real or imagined) of any natural resources. The French settled in northern America to fish and trade for furs, believing that they had found, at Québec on the St. Lawrence River, a route to the western frontier of the continent. However, they would maintain a persistent interest in the shorelines of the South before reverting to their first choice.Charlesbourg-Royal 1541–1543 (Cap-Rouge, Quebec): A Port of Call in the Crossing of the Continent (show)

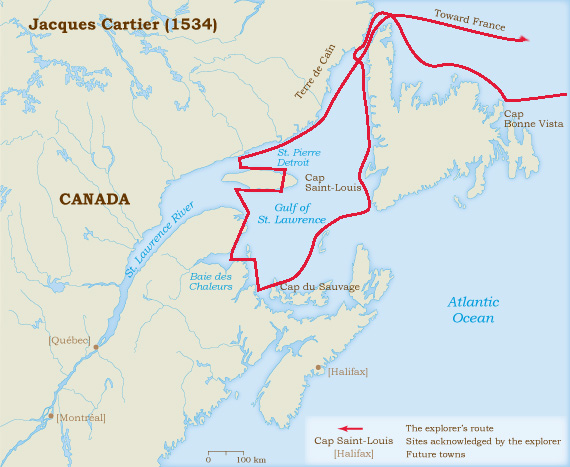

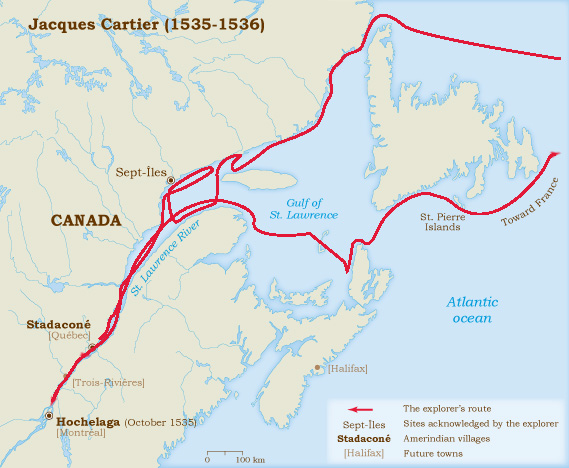

It was no coincidence that François I decided to send the first French colonists to settle at Cap-Rouge. For at least half a century, hundreds of French sailors had been crossing the Atlantic bound for Newfoundland, where they spent the summer months fishing and trading for furs. These sailors had time to become acquainted with the land and its inhabitants. Furthermore, three voyages of exploration commissioned by the king made it possible to expand knowledge of the coast of North America. In his report on his voyage along the east coast of the continent in 1524, Giovanni Verrazzano explained: “My intention was to reach Cathay and the far eastern coast of Asia, but I did not expect to encounter the obstacle of an unknown land.” He added: “All of the lands encountered were called Francesca, in honour of our King François.” The cartographers who rendered the voyage of Verrazzano called the land he approached “Nova Gallia” (1529) or “Nova Francia.” New France was born, at least on the maps. The continent had to be explored. It gradually allowed explorers to chart its mysteries through various expeditions, led by the English, Spanish and Portuguese. Their navigational secrets reached the French court. Following Verrazzano, France sent two expeditions, led by Jacques Cartier, a Breton sailor with knowledge of the fishing areas off Newfoundland and Cape Breton Island. In 1534, Cartier limited himself to exploring Newfoundland and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The existence of the St. Lawrence River would only be revealed later, by two young St. Lawrence Iroquoians, Taignoagny and Domagaya, whom the navigator captured in the Gaspé. This knowledge proved decisive: during Cartier’s voyage of 1535, he set a direct course for this major water route, the St. Lawrence, which, according to his young captives crossed a vast area of unknown boundaries called “Canada.”

Origin of the name “Sainte-Croix”

On September 14, 1535, Cartier arrived at the mouth of a river where he chose to lay up his ships. He named the river the “Sainte-Croix,” or “Holy Cross,” after the feast day of the Holy Cross, celebrated by the Catholic Church to commemorate the putative discovery of the True Cross (on which Jesus Christ suffered and died) by Saint Helena in the 4th century. Later, between 1615 and 1625, the Recollets would re-name this river the Saint-Charles, as it is known today, in honour of their protector, Charles de Boves, the grand vicar of the diocese of Rouen.

Why the Sainte-Croix River?

It is while returning his young Iroquoian captives to their home village of Stadacona (at present-day Quebec), that Cartier chose to establish his settlement. Near the Sainte-Croix River, he observed the presence of many Native encampments. About 500 people were gathered at Stadacona alone. One large island that he named “isle de Bacchus” (Île d’Orléans), appeared particularly fertile, since it presented “a very goodly land and level […] full of woods, without having any tillage.” There was a good harbour nearby. At first, Cartier was warmly received by Chief Donnacona and the compatriots of the two Iroquoian captives he was returning. The site of Stadacona proved a good choice for a permanent settlement. The 112 crew members set up camp on the north bank of the Sainte-Croix River for the winter of 1534–1535. A small defensive fort was built of logs, but the men lived on the two largest ships, the Grande Hermine and the Petite Hermine. True to his mandate, Cartier wasted no time in equipping the pinnace Émérillon, on September 19, to travel to Hochelaga (Montréal), and then as far as possible toward the source of the St. Lawrence River. He was also seeking, on the express wishes of King François I, information on the existence of minerals. Despite the prosperity of Hochelaga, its location at the crossroads of several rivers and the warm welcome offered by its inhabitants, Cartier understood that the St. Lawrence River did not cross the entire continent but that other water routes might do so. After a harsh winter, Cartier’s ships set sail for France on May 6, with a crew reduced by 25 men who had died of scurvy. The captain brought back with him ten Native captives, including Chief Donnacona, who – it was hoped – would be able to persuade François 1 of Canada’s many attractions. However, the ambitions of the King of France for his undertakings in the New World had to be set aside because of other concerns.

Spain and Portugal: Rivals

The choice of a colonial base also had to take into account the settlement in North America of two major powers of the era, Portugal and Spain. France was watched by its rivals because its king refused to comply with the papal bull Inter caetera (1493), which divided newly discovered territories between these two powers. In 1533, at the request of the King of France, Pope Clement VII clarified that the bull “only pertained to known continents and not lands [that would be] subsequently discovered by other crowns.” In 1556, the publication of Jacques Cartier’s account of two voyages, by Ramusio, in Italian, only served to aggravate the concerns of France’s rivals.

As a result, the next expedition to leave France, in 1541, was very closely monitored by Spain, Portugal, and England. The commission of Viceroy, granted to the courtier Jean-François de La Roque de Roberval on January 15, 1541, demonstrated the importance of the expedition: this was no longer merely a voyage of exploration commanded by a sailor, but the real point of departure for a colonial enterprise governed by a high dignitary of the Court. All of the operations were magnified by observers: a Spanish spy would even go as far as exaggerating the number of colonists embarked on the ships, reporting them to be 1500 in number, whereas fewer than 500 individuals actually went on the voyage. Despite the protests of the courts of Spain and Portugal, the preparations continued. Prisoners were recruited as colonists by Cartier (about 50) and Roberval (about 30) from their districts. They were not freed but instead voluntarily deported. Private funds were invested, essential to the financing of such a costly expedition. On May 23, 1541, Cartier left Saint-Malo in command of five ships for a difficult crossing that would take three months.The Misconception of Others

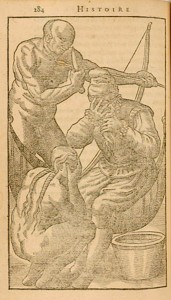

The French explorers of the xvith century knew little about the populations inhabiting the Americas and approached them with many preconceived ideas. Believing he had arrived on the shores of Asia, Verrazzano was astounded to find people who did not fit familiar descriptions of Chinese people or Indian people of India: partial nudity concealed by feathers, free love, the apparent absence of laws and property, and the practice of anthropophagy (the contemporary term for cannibalism) were among the traits that would henceforth characterize the “savage” in the eyes of European voyagers. The entire misunderstanding is rooted in the term “Indians,” as they were called. Jacques Cartier was not exempt from the unfortunate consequences of this mistake. The use of force in abducting Native people to France, both in 1534 and in 1536, prompted mistrust. The Amerindians interpreted a number of gestures of authority as an outrage, such as planting a cross at Gaspé in 1534, or building a fort on the edge of the Sainte-Croix River without securing agreement from the inhabitants. Worse still, Cartier’s decision to go to Hochelaga (Montreal) in 1535 despite the protests of Donnacona was understood as a declaration of war. Cartier himself lost all trust in his interlocutors; he accused them of dissembling, deceit and offence upon offence.

Cartier’s Voyage of 1541

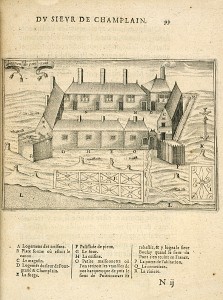

Despite this unpromising beginning, when Cartier returned to Stadacona in 1541 he and his companions were at first welcomed. The Stadaconan chief, Agona, presented him with a type of headdress called an esnoguy, “which he wore on his head as a crown and he placed it on the head of our captain.” Cartier refused the esnoguy and gave Agona and his wives a few small gifts that the chief quickly understood were of little value. In the face of renewed hostility, Cartier relinquished the site at Sainte-Croix (Saint-Charles River) and found another more defensible location, a little further west, on the edge of the Cap-Rouge river, in which to settle. It was on a steep cliff, ranging in height varied from 35 metres above the river on the west, to 45 to 50 metres on the southern and western sides. Cartier “found [the site was] better and more commodious to ride in and lay his ships, than the former.” On the edge of the cliff, he had two lodgings built: “[…] two courts of buildings, a great tower, and another of forty or fifty feet long, wherein there were divers chambers, a hall, a kitchen, houses of office, cellars high and low, and near unto it were an oven, and mills, and a stove to warm men in, and a well before the house.” There was also “another lodging, part whereof was a great tower of two stories high, two courts of good building, where at the first all our victuals and whatsoever was brought with us was sent to be kept; and near unto that tower there is another small river. […] In these two places, above and beneath, all the meaner sort was lodged.”

At the bottom of the cliff, a guard house and a water mill made it possible to monitor all suspicious traffic on the river and provided easy access to the Cap-Rouge River, where the ships were moored. The deciduous forest bordering the site furnished wood for construction and fuel. The two sites were linked by a path that climbed the cliff. The tower was surround by a palisade. According to recent archaeological investigations the site covered nearly 60,000 square metres. This defensive type of construction is explained by competition from the Spanish who had attacked Cartier’s ships in 1541, as well as by the hostility shown by the native Stadaconans during a raid that caused 35 deaths. It had to house from 450 to 500 colonists: the 350 who accompanied Cartier and the other 150 whom Roberval was obliged to bring. The place was named “Charlesbourg-Royal,” in honour of the son of François 1, Charles d’Orléans. In June 1542, following a winter that was as harsh as the one of 1535–1536, Cartier decided to return to France with the colonists. Roberval left La Rochelle later than scheduled, on April 16, 1542, with three ships and “two hundred persons, as well men as women and divers gentlemen of quality.” On June 8, the ships dropped anchor at the harbour of Saint John’s (Newfoundland), where Cartier was located. Despite Roberval’s order, Cartier refused to go back to Charlesbourg-Royal and returned to France. On June 30, 1542, Roberval left Newfoundland and arrived at Cap-Rouge at the end of July. He settled in the fort built by Cartier, which he renamed “France-Roy.” Once again, the French confronted the rigours of winter and the hostility of the Native people. In the following spring, after briefly exploring around the Outaouais region, Roberval and his group abandoned the site at Cap-Rouge, and returned to France in early September 1543.A Mirage of Wealth

One of the attractions of the site at Cap-Rouge was the apparent existence of precious metals that Carter identified on his arrival: […] We found good store of stones, which we esteemed to be diamonds […] a goodly mine of the best iron in the world […] perfect refined mine, ready to be put into the furnace. And on the water’s side we found certain leaves of fine gold as thick as a man’s nail. […] And at the end of the said meadow within a hundred paces there is a rising ground which is of a kind of slatestone, black and thick, wherein are veins of mineral matter, which show like gold and silver; and throughout all that stone there are great grains of the said mine. And in some places we have found stones like diamonds, the most fair, polished, and excellently cut that it is possible for a man to see; when the sun shineth upon them, they glister as it were sparkles of fire. Roberval confirmed Cartier’s observations: “[…] gold which he had found. The latter they tested by smelting and found it to be genuine.” Furthermore, from Donnacona’s description of the Saguenay, Cartier decided that gold and other ore would be found there. This territory of undetermined boundaries would extend over an area from the Saguenay River to the Ottawa River. This is what prompted him to go to Hochelaga, “of purpose to view and understand the fashion of the saults of water, which are to be passed to go to Saguenay.” Roberval would follow suit, travelling to the confluence of the St. Lawrence and Ottawa rivers. The gold that was brought back to France proved to be pyrite, or fool’s gold, and the diamonds, vulgar quartz, hence the expression “as phony as Canadian diamonds.” Nevertheless, the explorers of François I were able to observe other, more undeniable resources. The soil’s fertility, the abundance of game in the forests, and plentiful resources of fish all promised the possibility of a prosperous settlement. However, people had to deal with the harsh winters, a considerable hardship that took all immigrants by surprise. For subsequent settlers during the 17th century, surviving the cold season would remain a challenge.

Fort Coligny, Brazil (1555–1560): Supplying Normandy’s Textile Industry (show)

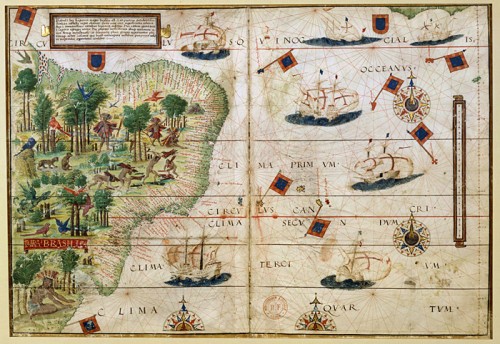

The disappointing experience of winters in the St. Lawrence Valley prompted France to seek a place with a milder climate for founding a colony. The fortuitous discovery in 1500 of the Brazilian coast by Portuguese explorer Pedro Alvarez Cabral triggered a ripple effect among French seamen, which brought the expeditions of the early 16th century there. Oral tradition evokes a number of voyages not officially established, such as those of Jean Cousin, in 1488, and Paulmier de Gonneville, in 1503, both natives of Honfleur. We also know with more certainty that captain Jean Denis, also from Honfleur, sailed the length of the Brazilian coasts in 1504, and that his pilot Gamart also did so around 1519, followed by Jean Parmentier a year later. In 1528, Verrazano, and in 1551, the cartographer Le Testu, also visited these coasts, trading with Aboriginal peoples. The strong competition between Portuguese and French merchant ships continued: in 1530, the French had captured more than 300 ships.

Dyes destined for the textile industry in the north of France and Europe were among the goods sought after in Brazil. This was the context in which a type of wood called brazilwood, originating from the Indies and known since the 12th century for its properties as a dye, appeared in Normandy. This dyewood, yielding a brilliant red colour, and much less costly than madder, spurred many a voyage across the Atlantic. Although dyewood dominated trade in Brazil, pepper, cotton, exotic animals and various tropical products were also of interest. In 1547–1548, at least 14 French ships engaged in commerce with local populations.“Indians” from Brazil in France

Many “Indians” from Brazil embarked on French ships bound for Normandy, attesting to the existence of peoples unknown to Europeans. Several representations in Norman churches provide evidence. In 1550, for Henri II, King of France, the Queen and the court visiting Rouen, battles were enacted between Aboriginal Tupinambas and Tabajaras, with residents of Rouen, wearing Indian apparel, and “fifty natural savages freshly brought from the country.” In 1558, the commander of Fort Coligny also brought some fifty Brazilians to France who were sent to stay with French families. In the early 17th century, François de Razilly (from San Luis) took six Tupinambas to Paris, who would be baptized with great pomp and circumstance in the presence of Louis XIII and his mother Marie de Medici.

These South American people aroused the curiosity of the French, particularly writers. The main account is that of Jean de Léry, companion to Villegagnon in 1557, who stayed for 10 months at Fort Coligny and subsequently published the Histoire d’un voyage faict en la terre de Brésil autrement dite Amérique (“History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, also called America”) (1578). Supplemented through six subsequent editions, published during the author’s lifetime and translated into Latin, the work was read throughout Europe. It offers a rather dark view of Native Americans, who are represented in fifteen engraved plates. In 1580, Montaigne addressed the topic in the chapter “On Cannibals” in his Essays (I, 31). He wavered between attentive objectivity and controlled reserve. During the Age of Enlightenment, Léry’s tale also inspired the Abbot Prévost and, after him, Diderot and the Abbot Raynal.The Supremacy of Norman Sailors

In the 16th century, the French sailors who ventured to sail the Brazilian coasts were mostly Normans. Open to both the North Sea and the Atlantic, their ports were particularly well located for maritime trade. Rouen, a river port on the Seine, acted as a redistribution centre for Paris, Orléans and the Loire, as well as for northern Europe. Confident of their power, wealthy Norman merchants, such as Jean Ango of Rouen, succeeded in asserting themselves as the major suppliers of brazilwood by giving chase to non-Norman French ships.

Fort Coligny

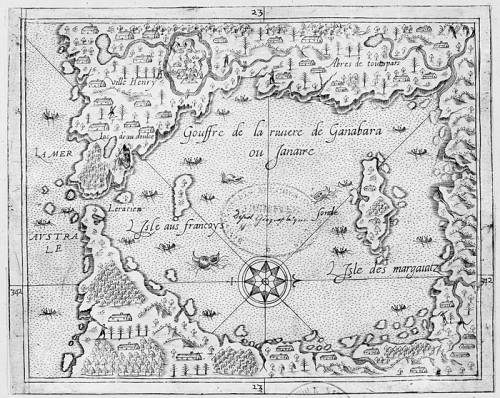

In 1555, an undertaking approved by the French admiral Gaspard de Coligny and partly financed by the king aimed to colonize a bay on the coast of Brazil. Nicolas Durand de Villegagnon, Knight of Malta, commanded the small fleet of three ships that left the port of Le Havre on July 12, 1555. On November 10, 600 men landed in a bay called “Ganabara” by the Aboriginal people and “Geneure” or “Janeiro” by the Portuguese. The French considered the bay “highly pleasant, covered in abundant palm trees, cedars, brazilwood trees, lush aromatic shrubs all year round.” They built a fort on an island of the bay of Rio de Janeiro, which Villegagnon called “Fort Coligny.” Colonists immediately set about gathering dyewood.

The colony consisted of Catholics and Protestants who, after arriving, rediscovered their reasons for dissension. Villegagnon’s rigid authority only aggravated the situation, and uprisings occurred. In March 1557, Protestant reinforcements arrived in Fort Coligny, sent from Geneva by the Protestant reformer John Calvin. The atmosphere further deteriorated and Villegagnon decided to expel the recently arrived Calvinists, after a stay of less than one year. In 1559, the commander also returned to France, leaving his post to his nephew, the Sieur de Bois Le Comte. The following year, the Portuguese destroyed Fort Coligny and, in 1565, they founded Rio de Janeiro. They named the island of Coligny after Villegagnon: Virgalhão, Viragalhão or Vila Galhão. The prevailing climate of religious tension in France was hardly conducive to reconquering the Brazilian colony. News of the taking of Fort Coligny by the Portuguese was greeted with the utmost indifference. Nevertheless, thanks to the alliance between the French and Aboriginal peoples, the French trade in brazilwood would continue until the mid-17th century.The Amazons of Brazil

Another French colony briefly existed on the northern coast of Brazil, at São Luis do Maranhão. In 1605, Henri IV appointed the Breton Daniel de la Touche, Seigneur de la Ravardière, “lieutenant general of the lands of America from the Amazon River to Trinity Island.” The Amazon region had been mythologized through the legend of women soldiers and rumours of the existence of precious metals. It was not until 1612 that the colony took shape. Commissioned by the Queen regent Marie de Medici, the Catholic François de Razilly, his two brothers, Isaac and Claude, and the Protestant Daniel de La Ravardière established about twenty hamlets and built Fort Saint-Louis on the island of São Luis (or Maranhão). They were accompanied by Catholic missionaries and a few hundred colonists. The colony, that was supposed to be the keystone of Equinoctial France, was intended to extend as far as the Orinoco. Attacked by the Portuguese in 1613, De La Ravardière’s French colonists had to surrender on November 3, 1615. However, some of them remained at São Luis, under Portuguese control. The French settlement in Brazil experienced little development: the French did not make any efforts to migrate or colonize that would create a permanent situation. Today, French Guiana, originally a colony subjected to a series of setbacks during the 17th century, is the distant descendent.

Fort Caroline, 1564–1565 (South Carolina): A Huguenot Colony (show)

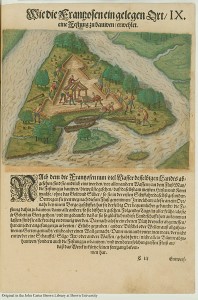

An Attempt at Charlesfort (Parris Island)

Captain Ribaut decided to settle his band on an island off South Carolina, today, Beaufort or Parris Island, located in an archipelago between Port-Royal Sound and St. Helena Sound. It was a fortified construction, built with the assistance of the Cusabo people. The habitation was called Charlesfort, in honour of the King of France, Charles IX. Outfitted as a base for corsairs and pirates, this site was intended as a beachhead for fighting Spanish settlement in the Americas. According to recent archaeological excavations, the spacing of the buildings was similar to that of the Cartier-Roberval site at Cap-Rouge. After leaving a few men at the River May and about thirty others at Charlesfort, Ribaut left America in June 1562 with pearls, silver and fur to show Admiral Coligny the importance of the location. A supply shortage and greed spread unrest among the men left behind. Some went into the interior seeking precious metals and food from the local Guale people, others boarded a makeshift boat bound for Europe and were picked up by an English ship. Those who remained at Charlesfort were attacked by the Spanish led by Manrique de Rojas, who completely razed the settlement. A Spanish fort, called San Felipe, would be built there in 1565 and would endure for about twenty years.

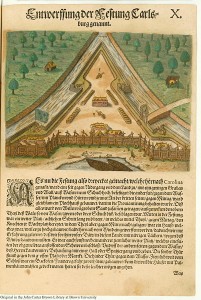

Spanish Supremacy

In 1564, an expedition of three vessels carrying 300 emigrants, led by René de Laudonnière, made a last-ditch voyage to bring fresh supplies to the few men remaining at Charlesfort. The commander then returned to the River May hoping to find the gold, silver and copper that the Timucua had mentioned. He built Fort Caroline, also named in honour of Charles IX. The third voyage, led by Jean Ribaut, consisting of seven ships and 600 colonists, arrived at River May on August 27, 1565. Settled for barely a week, the French colony was attacked by the Spanish from San Augustine, led by Menéndez de Avila who had learned of the French settlement’s location from local Native people. Following a period of resistance, the French capitulated on September 20; ships packed with fugitives managed to reach France. The French colony in Florida was definitively lost. The fort, now under Spanish command, took the name of San Mateo, and the French who had not been able to flee were massacred.

The tragic end of the French colony gave rise to many writings and illustrations focusing on the cruelty of both the Aboriginal people and the Spanish, who conquered the settlement. Very little is said about the Huguenot religion, except to justify its presence to oppose that of the Spanish Catholics. These writings also reveal profound differences between colonists and Aboriginal peoples. The colonists, coveting precious metals, relied on the latter for subsistence in exchange for European objects. The Aboriginal peoples appealed to the newcomers’ military forces to fight their enemies. The colonizers would long remember the many misunderstandings throughout the 17th century.Île Sainte-Croix, 1604–1605 (Maine and New Brunswick): A Temporary Settlement (show)

Severely stung by the failures in Brazil and Florida, the French withdrew further northward, to the area at about 45° latitude. They were familiar with the area, having travelled it for at least a century, fishing and conducting the fur trade. These lands were not coveted by the Spanish or the Portuguese, who instead staked their claims on the southern continent. In addition, the dramatic wintering of Cartier’s and Roberval’s colonists on the banks of the St. Lawrence River prompted the French court to find a site where winter was not as harsh. In 1563, when Ribaut and Laudonnière brought colonists to Florida, the Norman Étienne Bellanger was commissioned to found a trading post in Acadia. Shortly after dropping anchor in the Baie Française (Bay of Fundy), he returned to France with a large cargo of furs traded from local Native people. Acadia, a territory which Verrazzano called “Arcadia” for the fertility of its soil (in reference is to Greek mythology) once again attracted French explorers. In 1598, the Marquis de La Roche, a Breton, secured a monopoly on the fur trade on the condition that he found a settlement on Sable Island, off the coast of Cape Breton Island. Once again, most of the crew did not survive the winter. A few poor survivors were repatriated to France on cod-fishing ships. In 1600–1601, the expedition from Tonnetuit to Tadoussac, led by Pierre Chauvin of Dieppe, met with the same fate. Even so, the King of France persisted with his colonial plans, still hoping to discover rich minerals and wishing to assert the political personality of France.

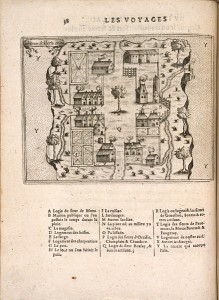

On November 8, 1603, Henri IV appointed the Huguenot Pierre Du Gua de Monts Lieutenant-General “of the coasts, lands and confines of Acadia, Canada and other places in New France.” For ten years, the Lieutenant-General engaged in settling 60 colonists per year and to evangelize the inhabitants, in return for the monopoly on the fur trade. In spring 1604, he landed at Acadia with ships laden with materials for settling 80 colonists and establishing trade. They settled on Île Sainte-Croix, located on the river of the same name about six kilometres from its mouth. (Today, the river forms the boundary between New-Brunswick and the State of Maine, in the United States). In addition to its accessibility by boat, Île Sainte-Croix seemed to offer the colonists good security, since they could easily see attackers approach and defend themselves. At less than one kilometre from the continental shoreline, the colonists thought that boats would be adequate for getting supplies on the continent as well as for trade with the Aboriginal peoples.A Deadly Winter

The Atlantic coast and its inhabitants were familiar to most immigrant colonists, at least during the spring and summer. On their arrival, they planted gardens on the island and along the north shore of the river. Then they built buildings with the materials brought from France. Archaeological investigations indicate that the buildings were arranged in a fashion to that employed by Cartier and Roberval at Cap-Rouge, and that of Ribaut and Laudonnière in Florida. Others, under the command of Samuel Champlain, explored the Atlantic coast toward the south and went up the Penobscot River for about 80 kilometres, bringing back the first precise descriptions of that region.

The harsh winter at Sainte-Croix was particularly difficult. The cold was so intense that blocks of ice sweeping along the river prevented the boats from leaving the island. The resources of the continent now inaccessible, 35 or 36 of the 80 colonists died of scurvy or other diseases before the arrival of further supplies on June 15, 1605. As a result, seeking a more welcoming place, Du Gua de Monts and Champlain resumed exploring further south, as far as Cape Cod. On this journey of about 600 kilometres they discovered lands inhabited by more sedentary First Nations, who grew corn and were less attracted to hunting fur-bearing animals than their neighbours in Acadia. Having already experienced the capture of some of their members by European voyagers, these Native people were not prepared to welcome the newcomers and were openly hostile. Circumstances seemed to contain the small French colony in the northern part of the continent, at around 45° latitude. Before returning to France, Du Gua de Monts transported the survivors of the expedition to a more sheltered place, within the Baie Française (Bay of Fundy), at Port-Royal.Port-Royal 1605 (Nova Scotia): A Capital for Acadia (show)

Three painful experiences helped direct the French towards an interior, continental location in which to found New France. Port-Royal offered shelter from the formidable northwest winds, at the entry of a river that would later be called “Du Dauphin.” Cartier had called this place Port Réal on a map made by Ramusio (1556). With materials from the buildings of Sainte-Croix, Du Gua de Monts built a habitation on the north side of the basin, “in front of the island at the entry to the river.” For protection against the cold and any possible attacks, the construction took on a four-sided shape, with buildings and walls, surrounding a large courtyard. There was a platform equipped with four canons, all surrounded by a basic palisade. The gardens were located nearby, between the habitation and the river. In addition to the security of the location, the French found invaluable friends and suppliers of furs at Port-Royal, among the Souriquois and their chief Membertou, who offered them an entirely loyal alliance. The winter of 1605–1606 was less destructive than that of the previous year. Of the some forty men living at Port-Royal, between 6 and 12 died of scurvy. The cold was less severe, and the colonists had access to fresh food thanks to their garden, a trout farm and the game that the Souriquois brought to them.

Although the outlook for settlement at Port-Royal appeared favourable, in fall 1606, the French began looking for a new location further south. Champlain and his crew sailed the Atlantic coast as far as the island they called La Soupçonneuse (Martha’s Vineyard), but in no place did they find people as welcoming as those near Port-Royal. Moreover, the colonists were gradually learning how to withstand the dangers of winter. In 1606–1607, they did not lack fruit, vegetables, meat and fresh fish, or wine, amply stocked on departing La Rochelle. Despite favourable conditions, scurvy caused four to seven deaths, less than half the deaths in the previous year. The recruitment of about fifty men, who arrived in Port-Royal in late July 1606, reinforced the colony’s efforts to expand. Many of these immigrants would later exercise lasting influence over the emerging colony: from 1610 on, Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt and Claude de Saint-Étienne de La Tour and his son Charles oversaw a period of eventful governance in Acadia. Other skilled newcomers, such as the apothecary Louis Hébert, would later colonize Québec. The lawyer Marc Lescarbot mainly contributed to the well-being of the colonists of Port-Royal through his sense of community and his talent for providing pleasant repasts and other forms of entertainment. He left precious written testimony, supplementing that of Champlain, about the era of the founding of Acadia.Du Gua de Monts Loses his Monopoly

In spring 1607, the colonists again prepared to sow wheat, rye, barley, hemp and vegetables when a messenger arrived on May 24 announcing that the ten-year trade privilege of Du Gua de Monts had been revoked. Through pressure from competitors, particularly the merchants of St. Malo and the Basques, combined with the opposition of De Sully, Henri IV’s principal minister, Du Gua de Monts lost his monopoly after only three years. Disappointment was keenly felt by all the men who had taken such care and pleasure in making Acadia a place where France could establish a settlement, and carry on trade and agriculture in harmony with Aboriginal peoples. After the last harvests in early September, all of the colonists returned to France. They left their habitation in the care of the Souriquois Chief Membertou until their return, in 1610, under the command of Poutrincourt. Lescarbot’s verses eloquently express their regrets:

At the same time, at the end of summer 1607, under the command of George Popham, 45 Englishmen built Fort St. George on the Kennebec River. They wintered there in 1607–1608, supplied with the letters patent of King James I, who ordered them to take possession of the lands south of the 45° parallel North. The charter granted to them encroached on the territory granted to Pierre Du Gua de Monts. In 1613, Port-Royal was attacked by Samuel Argall. It was the first in a long series of conflicts over the boundaries of the respective territories of New France and New England. France would no longer seek a basis for settlement on the Atlantic coast south of Acadia.

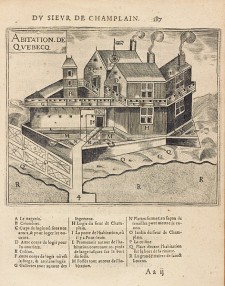

Québec 1608 (Canada): A Promising Trading Post (show)

Since the post at Port-Royal was not profitable enough for investors, the French turned to the interior of the continent to found New France. As a result of many representations made to persuade the King of France and his court, Pierre Du Gua de Monts’ monopoly was renewed in January 1608. Although established for only one year, this type of colonial management, conducted through exclusive trade privilege, would exist in various forms until 1663, when New France was placed under the direct control of the King. Samuel Champlain, the lieutenant of Pierre Du Gua de Monts, chose a location that he had appraised in 1603: it appeared secure, and Native people gathered there to trade and, in the fall, to fish for eels. Native camps could number in the hundreds of people. The French were familiar with the site, as a well-established toponymy demonstrates. Indeed, the name “Quebecq” appears on Normand Guillaume Levasseur’s map of 1601.

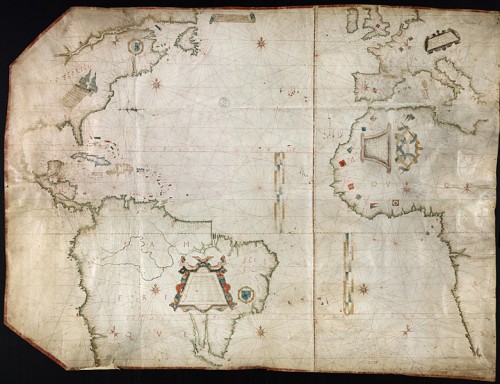

Map of Atlantic Ocean, North America | Cartes et plans, GE SH ARCH 5, Bibliothèque nationale de France

It Would Take More Than Furs

By exploring the territory, Champlain once again took up the primary function that he had previously carried out in the West Indies, on the Atlantic coast and in the St. Lawrence River. His goal was no longer to seek a base for a colony, for the site of Québec appeared to be a good choice. Now, the objective was to find new resources useful to France and to the colony that intended to establish a lasting settlement. For the colonists, the arable lands surrounding Québec, in particular on Île d’Orléans, offered good possibilities. The land had to be populated and worked so that it would feed a few dozen colonists who would winter at Québec in subsequent years. France expected high quality furs to meet thedemands of the European market. And people still dreamed of precious metals such as those found in South America. It was up to Champlain to carry out a survey of territory and water routes that might lead north, west or south. In 1608, he made his way up the Saguenay River to Chicoutimi. The following year he navigated the Richelieu River as far as Lake Champlain, where he confronted the Iroquois and learned that the Dutch were in the process of establishing a powerful post nearby, at the mouth of the Hudson River (the future New York). In 1613, he explored the Ottawa River as far as Île aux Allumettes and, in 1615–1616, a major expedition took him to Huronia, on Georgian Bay, where he first glimpsed the Great Lakes. During these exploratory voyages, spread over a dozen years, Champlain sought to establish partnerships with the First Nations he encountered. The knowledge he gathered and the alliances he contracted would form the foundations for the French presence in North America.

Québec was making very gradual progress, but its existence would soon be threatened by English competitors. Despite the conditions of monopoly trade, the immigration program was not meeting its objectives. The first settler family, that of Louis Hébert did not arrive until 1617. Three years later in 1620, Champlain brought his wife, Hélène Boullé, with whom he had no children, and who would return to France in 1624. Recollet missionaries arrived in 1615 to convert the Native people, and the Jesuits followed in 1625. The Company of New France, a powerful merchant group also called the Company of One Hundred Associates, was founded by Richelieu in 1627; New France was under his jurisdiction and had to be populated in return for the profits the Company would derive. In 1628, the first ship bearing immigrants was captured by the Kirke brothers, who later seized Québec in the name of the English crown. It was only after Québec was returned to the Company, under the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1632, that immigration to New France resumed. In December 1635, on the death of the colony’s commander Champlain, New France only had 150 settlers, but 30 years later, when Canada became a royal colony, 3500 settlers of French origin were enumerated. Religious and governmental institutions began to structure society, and the military provided defence. New France was founded.Conclusion (show)

The first site where French colonists wanted to settle permanently was, in the end, Québec, which would become the capital of New France. But three quarters of a century separated the wintering of Jacques Cartier’s crews, in 1536 and 1542, from the construction of the Habitation of Québec, in 1608. In the meantime, French sailors and merchants struggled to find a place with a less deadly climate than that of the St. Lawrence Valley and above all, more profitable natural resources than fish and fur. Rio de Janeiro, Amazonia, Florida, Carolina, Île Sainte-Croix (Maine) and Port-Royal all presented apparently insurmountable obstacles to sustainable settlement, the competition proving too fierce. In Brazil, the French were chased out by the Portuguese and in the south of North America, by the Spanish; in Acadia, they came up against the ambitious English and encountered the Dutch merchants of Manhattan.

The quest for enchanted southern islands proved a disappointing, utopian venture. The French explorers still had a fallback position, and from there, navigation, by chance, revealed great fish resources and fine animal pelts that the Aboriginal peoples brought to them in exchange for European goods. These commodities were less profitable and prestigious than the precious minerals mined by the Spanish and Portuguese. However these resources drew the French into the interior of the continent and pushed them westward, where they (the French) felt certain they would reach the ocean that washed up on Asian shores and would lead them to Asian riches. At the same time, partnerships and treaties with Aboriginal First Nations invited settlement in the fertile lands of the St Lawrence valley. However, the French would continue to covet the territories of the South and would also settle in the West Indies and develop, in Louisiana, an extension of New France. The rivalries between the great powers of Western Europe, their imperialist ambitions and economic appetites sketched out the colonial spaces of the Americas; the coincidences of military and economic history led France to develop, over two centuries, a vast empire in North America, based in Québec, capital of New France.Suggested Readings (show)

ABREU, MAURICIO A. “La France Antarctique, colonie protestante ou catholique?” in MICKAËL AUGERON, DIDIER POTON and BERTRAND VAN RUYMBEKE, (ed.) Les Huguenots et l’Atlantique, vol. 1, “Pour Dieu, la cause ou les affaires,” Éditions Les Indes savantes, Presses de l’Université Paris-Sorbonne, 2009. BIDEAUX, MICHEL, ed. Jacques Cartier, Relations, Montréal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 1986. Coll. Bibliothèque du Nouveau Monde. BOTTINEAU-FUCHS, YVES. “Indiens et Normands au début du xvie century,” in Les Normands et la mer. Actes du xxve congrès des sociétés historiques et archéologiques de Normandie, Cherbourg, 4-7 October 1990, Musée Maritime de Tatihou, 1995. BRAUDEL, FERNAND, ed. Le Monde de Jacques Cartier. L’aventure au XVIe siècle, Montréal/Paris: Libre-Expression/Berger-Levrault, 1984. CHALINE, JEAN-PIERRE, ed. 1492-1992 Des Normands découvrent l’Amérique, Rouen: Société de l’histoire de Normandie, 1992. DOIRON, NORMAND. “Sainte-Croix: le nom et lieu,” in Études canadiennes/Canadian Studies, Association française des Études canadiennes, Bordeaux, n° 17, December 1984, 99-106. DUVIOLS, JEAN-PAUL. L’Amérique espagnole vue et rêvée. Les livres de voyages de Christophe Colomb à Bougainville, Paris: Éditions Promodis, 1985. The European Vision of America. Catalogue of the exhibition to honour the Bicentennial of the United States, organized by the Cleveland Museum of Art with the collaboration of the National Gallery of Art, Washington and the Réunion des musées nationaux de Paris, Paris: Éditions des musées nationaux, 1976. LA RONCIÈRE, MONIQUE DE, and MOLLAT DU JOURDIN, MICHEL. Les portulans. Cartes marines du xiiie au xviie siècle, Paris: Nathan, 1984. LITALIEN, RAYMONDE and VAUGEOIS, DENIS, ed. Champlain. La naissance de l’Amérique française, Québec: Septentrion, 2004. LITALIEN, RAYMONDE, PALOMINO, JEAN-François, and VAUGEOIS, DENIS. La Mesure d’un continent. Atlas historique de l’Amérique du Nord, Québec: Septentrion, 2007. TRUDEL, MARCEL. Histoire de la Nouvelle-France, I: Les vaines tentatives 1524-1603, Montréal: Fides, 1963 TRUDEL, MARCEL. Histoire de la Nouvelle-France, II: Le comptoir, 1604-1627, Montréal Fides, 1966.