The issue of slavery in Canada has long been glossed-over by historians and by Canadian society in general. Substantive recognition of this past history of slavery did not begin until the 1960s. Nevertheless, slavery was actively practised in New France, both in the St. Lawrence Valley and in Louisiana. This institution, which endured for almost two centuries, affected the destiny of thousands of men, women and children descended from Aboriginal and African peoples.

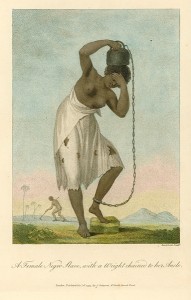

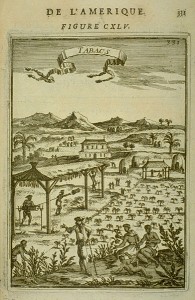

Labouring under the eye of the overseer, end of the eighteenth century

The Introduction of Slavery

Slavery was introduced to New France in stages. A first slave, a young boy originally from Madagascar or Guiney, arrived with the Kirke brothers in 1629. Before leaving Quebec three years later, the latter sold him for the sum of 50 écus. The boy soon passed into the hands of the colonist Guillaume Couillard and received the name “Olivier Le Jeune”. As Le Jeune was described as Couillard’s “domestique” (servant) in the record of his burial in 1654, it is plausible that he had been manumitted by his master.

This exception aside, black slaves arrived in Canada only towards the end of the seventeenth century. Despite colonial officials’ oft-reiterated yearning to have African slaves imported to the colony, no slave ship ever reached the St. Lawrence valley. Those black slaves who arrived in the region came from the neighbouring British colonies, from which they were smuggled or where they were taken as war captives. A number of Canadian merchants also brought black slaves back from their business trips to the south, in Louisiana or in the French Caribbean.

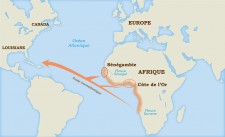

The geographic origin of African slaves

In Canada, the majority of slaves were not of African, but rather of Aboriginal origin. Native populations customarily subjugated war captives before the arrival of the French, but this practice acquired new meanings and unprecedented proportions in the context of western expansion. Beginning in the 1670s, the French began to receive captives from their Aboriginal partners as tokens of friendship during commercial and diplomatic exchanges. The Illinois were notorious for the raids which they led against nations to the southeast and from which they brought back captives. By the early eighteenth century, the practice of buying and selling these captives like merchandise was established.

The ethnic origin of Aboriginal slaves is occasionally specified in period documents. They included Foxes and Sioux from the western Great Lakes, Inuit from Labrador, Chickasaws from the Mississippi valley, Apaches from the American southeast, and especially “Panis”. The latter designation can be misleading. In its strictest sense it referred to the Pawnees, a nation which inhabited the basin of the Missouri River and which was heavily targeted by the allies of the French. Amongst colonists, however, their name rapidly became a generic way of referring to any Aboriginal slave. Many an “esclave panis” (Panis slave) who show up in the records, thus, was not Pawnee at all.

The situation was rather different in Louisiana. At the time of this colony’s establishment in the early years of the eighteenth century, Aboriginal slaves were harder to acquire and retain in bondage. Colonists, particularly planters, moreover preferred African slaves, whom they judged more apt to work in their indigo and tobacco fields. In Louisiana, the slave trade from Africa thus began in 1719.

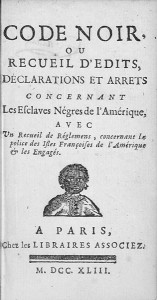

Code noir (The Black Code, first page)

In Louisiana, slavery was officially regulated with the promulgation of the Black Code in 1724, an adaptation of the law in force in the Antilles since 1685. This edict codified the status of slaves and free Blacks, in addition to the relationship between masters and slaves and between Whites and Blacks. The principal clause forbade inter-racial marriages, which nevertheless did not prevent concubinage between White men and Black women. The majority of Louisiana planters did not comply with this edict except when it suited them. Blacks, especially in Lower Louisiana, enjoyed much greater financial and cultural freedom than had been intended by the Code.

In Canada, there never was legislation regulating slavery, no doubt because of the small number of slaves. Nevertheless, the intendant Raudot issued an ordinance in 1709 that legalized slavery: “All Panis and Negroes who have been purchased and who will be purchased, shall be the property of those who have purchased them and will be their slaves; it shall be forbidden to said Panis and Negroes to leave their masters, and whosoever shall incite them to leave their masters shall be subject to a fine of fifty pounds.” This text legitimized the practice of slavery in Canada, which Louis XIV had authorized in 1689 (confirm the date of 1685 or 89). Before 1709, no law protected “the investment” of slave owners.

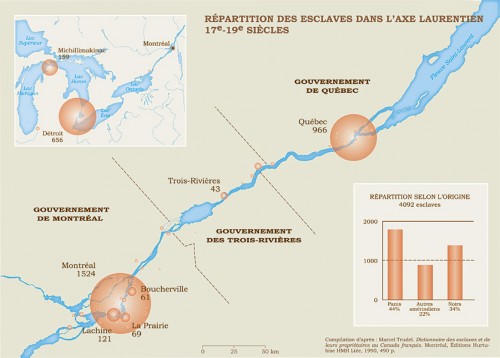

The historian Marcel Trudel catalogued the existence of about 4,200 slaves in Canada between 1671 and 1834, the year slavery was abolished in the British Empire. About two-thirds of these were Native and one-third were Blacks. The use of slaves varied a great deal throughout the course of this period. For the entire 17th century, there were only 35 slaves of which 7 were Blacks. Between 1700 and 1760, some 2,000 were enumerated, including both Natives and Blacks, and about as many from the Conquest until 1834. After 1760, the number of Black slaves in the colony increased considerably, from 300 to more than 800. This increase is attributable in large part to the arrival of the Loyalists in Quebec after 1783 who brought their own slaves with them.

Demographic repartition of the slave populations in the St. Lawrence Valley.

The slaves were generally very young: among the Panis, the average age would have been 14 years old and 18 years old for Blacks. The percentage of females among Aboriginal slaves was 57 percent. Among Black slaves the percentage of males was also 57 percent.

Slave, with a Weight chained to her Ancle, 1796, by John Gabriel Stedman

In Louisiana, in contrast, the number of Aboriginal slaves was always lower than that of Black slaves. Throughout the French regime, there were about 1,700, of which the majority were females who worked as household help and served as concubines for the French. They were often hardly ten years old. Their average age at death was 17 years, testimony to their vulnerability to European epidemics, as were the Panis slaves in Canada. Louisiana planters preferred slaves of African origin, who ran away in lesser number and who were healthier.

Between 1719 and 1743, the Company of the Indies (Compagnie des Indes), which held a monopoly on the slave trade, sent some 6,000 Africans to Louisiana. The majority of them were males since females were generally reserved for the slave trade in Africa and because field work required more robust manual labour. The majority were from Senegambia, the remainder came from the Angola-Congo region and the Bight of Benin. In contrast to Canada, which was a “society with slaves,” Louisiana was a “slave society.” The slave population, which was much higher, played an important role in the economic development of the region. Yet slavery was nevertheless less prevalent than in the French Antilles during the same period.

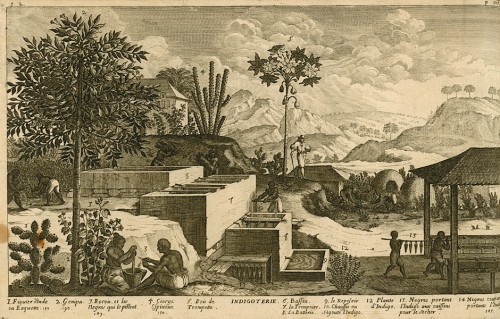

Indigo making, 1667 par Jean Baptiste Du Tertre

In the St. Lawrence Valley, slaves were in the service of the political and social elite, which existed primarily in Québec and Montréal: governors, intendants, clergy, religious communities, and military officers in addition to merchants and traders. In two-thirds of the cases, masters owned but a single slave.

Indigo, 1688, by Charles Plumier

In Louisiana, the presence of slaves was much more widespread. In Illinois, also called Upper Louisiana, nearly half the households had slaves. Of these, three-fourths owned no more than five. To the south, in the lower Mississippi valley, slave owners were even more numerous. In 1731, in New Orleans and in the surrounding region, there were about four Black slaves for every white inhabitant. In the 1760s, the ratio was two to one. These slaves worked on the great plantations under the supervision of a foreman, who was usually White.

In Canada, the colonial economy did not favour the growth of slavery because the economy’s two principal industries required little manual labour: The fur trade was controlled by a small group of professionals and essentially relied on the labour of Native fur trappers. Manual labour in families was sufficient for small farming operations. Furthermore, the purchase of an Aboriginal or Black slave was an unaffordable expense for settler-proprietors. A Black slave cost from 800 to 1000 pounds, that is, twice as much as an Aboriginal slave. In the 18th century, the annual average income of an unskilled worker was about 100 pounds. That of a bona fide artisan was from 200 to 400 pounds.

The African slave trade in Louisiana did not reach the same magnitude that it did in French Antilles. Effectively, it lasted for about 12 years, from 1719 to 1731, when the king of France resumed authority over Louisiana after having temporarily ceded it to franchise holders and investors. In the Antilles, before 1719, few Black slaves had been purchased individually. After 1731, the Compagnie des Indies (Company of the Indies) ceased sending ships to the region, judging the sale of slaves to the colony less profitable than in the French Antilles. However, certain individuals obtained slaves from the Antilles by seizing British ships or through smuggling. Some hundreds of slaves are estimated to have been obtained in this way.

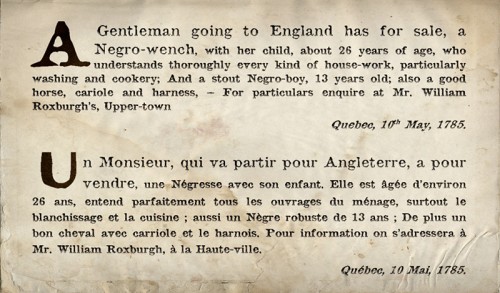

Announcement of sale of slaves appeared in the Quebec Gazette May 12 1785

In the New World, slave status was limited to Blacks and some Aboriginal people, and was based on the belief in the superiority of Whites. Unlike domestic servants or workers, slaves were considered private property: slaves belonged to an owner. As such, slaves could be “granted” (via an inheritance or by their living masters); loaned (to settle a debt, for example), bartered or sold, according to the wishes of their owner. Many such sales were recorded in official archives and in certain newspapers of the period.

Men, women and children became slaves against their will: they were removed from their community of origin as a result of armed conflicts or as part of the slave trade. A person could likewise be born into slavery.

In Canada, slaves lived under conditions comparable to those of immigrant workers. Even if their legal status was inferior, they enjoyed a certain quality of life and relative freedom in the performance of their tasks, since they shared daily life with their masters, who were usually members of the upper class. In addition, urban living allowed them to secure connections to Whites, in contrast to their counterparts in the southern colonies. Panis often held positions as bargemen or domestic servants. As for Blacks, in addition to household positions, they were able to work in a variety of occupations: wigmaker, hair-dresser, baker, cook, cooper, sailor, voyageur, armourer, goldsmith, printing press operator, and even executioner.

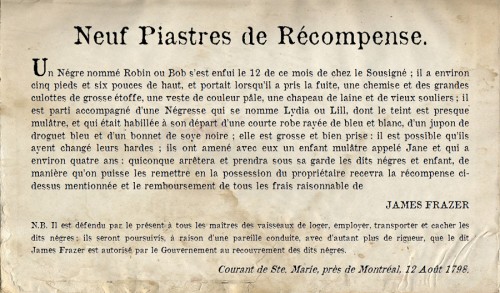

Escape of slaves published in the Quebec Gazette, August 10, 1798

A slave from Martinique who became a Quebec executioner

Only one Black slave discharged the duties of the maître des hautes œuvres—executioner—in Canada under the French regime: Mathieu Léveillé, from 1733 to 1743. Upon the death of the executioner, Jean Rattier, in 1723, the colonial authorities requested the ministry of the Navy to send a replacement, but the ministry’s advice was to send for a “Negroe” from Martinique. In fact, it was not until after having dealt with two incompetent executioners, a Parisian and a Londoner, that the authorities took the advice of the Ministry. Léveillé arrived in Québec City in 1733. He was uncomfortable in the Canadian climate and also suffered from depression. Seeking a solution, the intendant had the idea of buying him a wife. But when the wife-to-be arrived from the Antilles, Léveillé again became ill. So it was that the bachelor passed away in the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec on September 9, 1743 at the age of 34.

In Lower Louisiana, living and working conditions for slaves were substantially worse than in Canada. Isolated on large indigo and tobacco plantations, they were confined in “Negro shacks” and subjected to unrelenting work: ploughing, sowing, hoeing, harvesting, maintaining drainage canals and levees. Often malnourished and ill-clothed, they were also more vulnerable to illnesses. Slave masters did not, however, hesitate to have them medically treated in order to protect their investment.

Slaves were not all subjected to forced labour. Certain slaves were regarded as agricultural or livestock breeding “technicians” and others as skilled artisans. They also worked as household servants, especially women, primarily in cities. In Illinois, slaves were less financially independent, but benefited from better food and better working conditions than those in Lower Louisiana. For example, in Illinois, slaves could sometimes sell some vegetables from their gardens for a profit or offer their services to other Whites after approval by their master and realize a small profit. Moreover, there was no segregation in the work assigned to Whites and to Blacks: their tasks were very similar to those of French or Canadian rural inhabitants.

Relations between slaves and masters depended directly on both the living and working conditions of the slaves. In Canada, a slave lived in the home of the slave’s master, often with other servants or workers who were white, and shared the same living conditions. Consequently, the slave-master relationship was probably closer than in Louisiana, which is not to say, however, that it was harmonious. Conflicts mentioned in judiciary records and accounts of runaways (escaping slaves) that appear in newspapers of the French regime attest to a sometimes difficult co-existence.

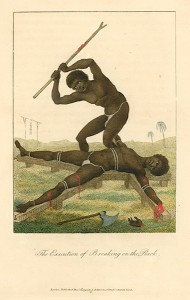

The Execution of Breaking on the Rack, 1796, by John Gabriel Stedman

In contrast to Canada, in Louisiana, the unequivocal domination of the master over the slave clearly constituted the norm. Violence seemed omnipresent and generally took the form of blows delivered with a truncheon or whip, but also the withholding of food or putting a slave in irons. Such actions were taken when a slave poorly performed a task or refused to work. Slaves were the victims of poor treatment and acts of cruelty, even if such acts were generally condemned. The Black Code in effect forbade recourse to torture and required masters to act as “good family fathers” with respect to their slaves. That did not prevent all manner of abuses. It was, in fact, excessive violence that greatly contributed to runaways. The interruption of the importation of slaves in Louisiana, in 1731, would have “eased” their living conditions in comparison to those in other French colonies.

The runaway slave, who shall continue to be so for one month from the day of his being denounced to the officers of justice, shall have his ears cut off, and shall be branded with the flower de luce on the shoulder: and on a second offence of the same nature, persisted in during one month from the day of his being denounced, he shall be hamstrung, and be marked with the flower de luce on the other shoulder. On the third offence, he shall suffer death.

Article 32 of the 2nd edition of the Black Code, issued by Louis xv in 1724.

In Canada, slightly more than one hundred slaves were freed under the French regime, yet to date, little is known of their circumstances. Manumission, the act of freeing a slave, occurred when a master granted freedom to a slave in recompense for the slave’s good services. A freed slave enjoyed the same rights and privileges as any free citizen. If a slave had had the opportunity to learn a trade, as a free citizen the slave would generally continue such work in his new life. Manumission did not, however, bring success to everyone: some became itinerants, beggars or thieves and others would disturb the peace.

In Louisiana, the number of freed former slaves was fewer than in Canada. In fact, the Black Code imposed restrictions on the manumission of slaves: the objective of the authorities was to limit the number of free Blacks in the colony to maintain a kind of barrier between Whites and free Blacks and, more generally, between Whites and Blacks. At the end of the French regime in Lower Louisiana, there were about 200 free Blacks. Many of them had served as soldiers in military campaigns against Aboriginal groups. In general, it was not in the interests of the Louisiana owners to free slaves: the slaves had cost them a great deal and played an important role in their economic success. Especially since after 1731, it became more and more difficult to obtain them.

In the Louisiana region, slavery was not abolished until 1865, but the situation was entirely different in Canada where, by the 18th century, to the use of slaves was becoming increasingly infrequent. In 1793, Upper Canada (today, Ontario) legislated for the first time against the importation of slaves, thereby heralding the gradual elimination of slavery. The same year, Lower Canada (Quebec) also presented a bill to abolish slavery. Several members of the Legislative Assembly, themselves slave owners, opposed the legislation. Finally, it was the courts who sealed the fate of slavery in the province: in various cases concerning the arrest of slaves for having run away from the domicile of their master, judges ordered the liberation and manumission of the fugitives. In 1833, the official abolition of slavery in the British Empire simply confirmed the existing status that had already prevailed for several years in Canada. However, it is impossible to state with precision the date when slavery disappeared from the country.

– BEAUGRAND-CHAMPAGNE, Denyse, Le procès de Marie-Joseph-Angélique. Outremont: Libre Expression, 2004.

– COOPER, Afua, The Hanging of Angélique. The Untold Story of Canadian Slavery and the Burning of Old Montréal. Toronto: Harper Collins, 2006.

– DAWDY, Shannon L., Building the Devil’s Empire: French colonial New Orleans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

– GREER, Allan, Brève histoire des peuples de la Nouvelle-France. Montréal: Boréal, 1998.

– HALL, Gwendolyn Midlo, Africans in Colonial Louisiana. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

– HAVARD, Gilles and VIDAL Cécile, Histoire de l’Amérique française. Paris: Flammarion, 2003.

– INGERSOLL, Thomas, Mammon and Manon in Early New Orleans. The First Slave Society in the Deep South, 1718–1819. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1999.

– LACHANCHE, Paul, “The Growth of the Free and Slave Population in Colonial Louisiana,” in Bradley G. Bond, French Colonial Louisiana and the Atlantic World. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005, pp. 204–243.

– SPEARS, Jennifer, “Colonial Intimacies: Legislating Sex in French Louisiana,” William and Mary Quarterly. 3rd Series, vol. 60, no. 1 (Jan. 2003), pp. 75–98.

– SPEARS, Jennifer, Race, Sex and Social Order in Early New Orleans. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

– TRUDEL, Marcel, Deux siècles d’esclavage au Québec. Montréal: Hurtubise, 2004.

– TRUDEL, Marcel, Dictionnaire des esclaves et de leurs propriétaires au Canada français, 2nd edition revised and amended. Montréal: Hurtubise, 1994.

– TRUDEL, Marcel, L’esclavage au Canada français: histoire et conditions de l’esclavage. Ste Foy: Presses de l’Université Laval, 1960.

– VIAU, Roland, Ceux de Nigger Rock: enquête sur un cas d’esclavage des Noirs dans le Québec ancien. Outremont: Libre expression, 2003.

– VIDAL, Cécile, “Africains et Européens au pays des Illinois durant la période française (1699-1765),” French colonial History, 2003, vol. 3, pp. 51–68.

– WINKS, Robin. Blacks in Canada. Montreal:McGill-Queens Press, 1966.