Beginning about 1,000 years ago, Europeans sailed to North America in search of natural resources and a sea route to Asia.

Encounters between First Peoples and the newcomers were characterized by curiosity, mutual distrust and sometimes violence. Yet they sought and found ways to coexist. A permanent European colony was the result.

One thousand years ago, First Peoples encountered Norse seafarers (sometimes called Vikings) along the shores of Eastern Canada. While the Norse did not stay, they now had knowledge of lands beyond the Atlantic Ocean.

Shortly after founding colonies in Greenland, the Norse sailed further west, to the eastern shores of Arctic and Atlantic Canada. Here they met Indigenous peoples. These encounters were not always peaceful, and Indigenous resistance to the Norse was a key factor in their failure to establish a permanent presence in North America.

Norse Voyages

Norse settlers from Iceland colonized Greenland during a period of global warming. They exploited pockets of land suitable for farming and hunted sea mammals. They imported other resources.

Norse from Greenland also travelled westward in search of essential materials such as wood. They established at least one small settlement in Canada, but their presence remained sporadic and temporary.

Norse Sagas

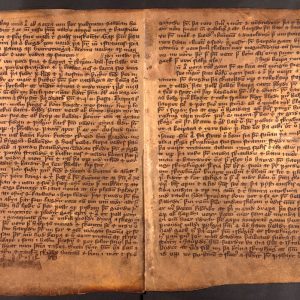

The Norse oral traditions known as sagas preserve a history of Norse activities in Greenland and North America. The earliest surviving written versions date to the 1300s. The Saga of Erik the Red relates how an expedition from Iceland led by Erik established a colony in southern Greenland in the late 900s. It continues with the story of his son Leif’s travels to North America, and his encounters with First Peoples who the Norse called Skraelings.

The Saga of Erik the Red

Two original manuscripts of this saga have survived. This page is from one that was produced in the early 1400s. Another is from the early 1300s.

Skálholt Map

In the late 1500s, Sigurd Stefánsson, a teacher from Skálholt, Iceland, used information from the sagas to create this map of the North Atlantic. Do you see any similarities with a modern map?

The Greenlander Saga

Listen to a description of the earliest known exploration of North America by a European, Leif, son of Erik the Red.

Transcript:

A traveller named Bjarni Herjolfsson had sighted land west of Greenland, while sailing from Iceland to visit his father. A few years later, Leif, son of Erik the Red — the founder of the European settlement in Greenland — explored this unknown land.

They made their ship ready and put out to sea. The first landfall they made was the country that Bjarni had sighted last. They sailed right up to the shore and cast anchor, then lowered a boat and landed. There was no grass to be seen, and the hinterland was covered with great glaciers, and between the glaciers and shore, the land was like one great slab of rock. It seemed to them a worthless country.

Then Leif said, “Now we’ve done better than Bjarni where this country is concerned — we’ve at least set foot on it. I’ll give this country a name and call it Helluland [flat stone land].”

They returned to their ship and put to sea and sighted a second land. Again, they sailed right up to it and cast anchor, lowered a boat and went ashore. The country was flat and wooded, with white sandy beaches wherever they went; and the land sloped gently down to the sea.

Leif said, “This country shall be named after its natural resources: it’ll be called Markland [forest land].”

They hurried back to their ship as quickly as possible and sailed away in a northeast wind for two days until they sighted land again. They sailed towards it and came to an island which lay to the north.

They went ashore and looked around. The weather was fine. There was dew on the grass, and the first thing they did was to get some of it on their hands and put it to their lips, and to them it seemed the sweetest thing they’d ever tasted. Then they went back to their ship and sailed into the sound that lay between the island and the headland jutting to the north.

One evening, news came that someone was missing: it was Tyrkir, the Southerner. Leif was very displeased at this, for Tyrkir had been with the family a long time. Leif got ready to make a search with 12 men.

They had gone only a short distance when Tyrkir came walking towards them, and they gave him a warm welcome. Leif quickly realized that Tyrkir was in excellent humour.

Leif said to him, “Why are you so late, foster-father? How’d you get separated from your companions?”

At first Tyrkir spoke for a long time in German and no one could understand what he was saying. After a while he spoke in Icelandic.

“I did not go much farther than you. I have some news. I’ve found vines and grapes.”

“Is that true, foster-father?” asked Leif.

“Of course, it’s true,” he replied. “Where I was born there were plenty of vines and grapes.”

Leif named the country after its natural qualities and called it Vinland [wine land].

From the Greenlanders Saga, translated by Magnus Magnusson and Hermann Palsson. In The Vinland Sagas: The Norse Discovery of America, by Magnusson and Palsson. Penguin, 1965, pp. 55-58.

A Norse Settlement in Newfoundland

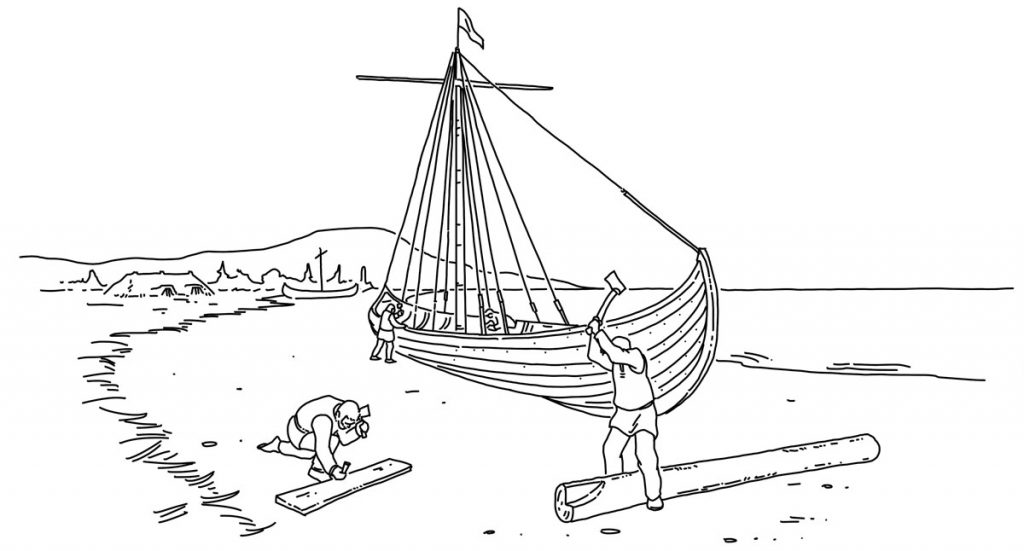

An archaeological site in Newfoundland provides definitive evidence of Norse settlement in North America. L’Anse aux Meadows consists of the remains of dwellings and workshops. These wood chips and metal fragments found at the site were likely left behind by Norse sailors repairing their ship about 1,000 years ago.

“There they found fields of wild wheat… and the vine in all places… Every rivulet there was full of fish…

There was great plenty of wild animals of every form in the wood…

Early one morning, as they looked around, they beheld nine boats made of hides.”

The Saga of Erik the Red

Evidence of Contact in the Eastern Arctic

Evidence of Inuit contact with the Norse has been recovered from a handful of archaeological sites in the Eastern Arctic.

The range of materials found at Skraeling Island might indicate that Inuit had encountered Norse traders or salvaged useful items from an abandoned ship. At other sites, yarn, possibly manufactured in Greenland, and other Norse manufactured items may have been acquired by Inuit through trade.

An Inuit View of the Norse

Inuit wooden figurines depicting Inuit people share distinct characteristics: round heads without features, short limbs without hands or feet, and typical hairstyles. However, the carving from the Okivilialuk archaeological site on Baffin Island is likely an Inuit artist’s portrayal of a Norse traveller. The figure appears to wear European rather than Inuit clothing. The artist has carved a cross on its chest. The Norse at the time were Christians, and may have worn such symbols.

New Sources of Materials

Archaeologists have recovered objects of Norse origin in Inuit sites. This demonstrates that Inuit integrated Norse materials, and possibly techniques, into their daily lives. Such items may have been acquired directly from Norse travellers or have come from abandoned shipwrecks. Arctic peoples were familiar with local metal sources prior to contact with the Norse. Iron from the Norse provided another source of metal for toolmaking by means of a traditional cold-hammer technique.

Norse objects from the Skraeling Island site

Nunavut, about 800 years ago

Norse objects1- Carpenter’s plane, wood, SfFk-4:3502

Norse objects1- Carpenter’s plane, wood, SfFk-4:3502

2- Knife, or ulu, iron and wood, SfFk-4:439

3- Chain mail fragments, iron, SfFk-4:2, 1189

4- Knife blade, iron, SfFk-4:1184

5- Cloth fragment, wool, SfFk-4:1234 Boat Rivets, ironThe Norse used these rivets to build a boat or ship. They held together the overlapping boards that formed the hull.

Boat Rivets, ironThe Norse used these rivets to build a boat or ship. They held together the overlapping boards that formed the hull.

Skraeling Island, Nunavut, about 800 years ago

CMH, SfFk-4:2816, 2817

Norse objects from other Inuit archaeological sites

Nunavut, 750 to 500 years ago

Learn more

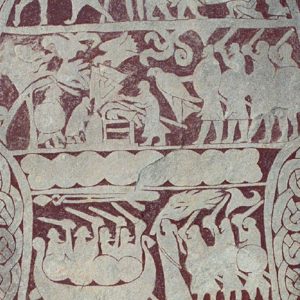

Photo at top of page:

Stora Hammars 1 Stela (detail)

Gotland, about 1200 years ago

Bengt A. Lundberg

Swedish National Heritage Board, ff941728

Collection

Collection

Resource

Resource