Audio

1950s The Experimental Years

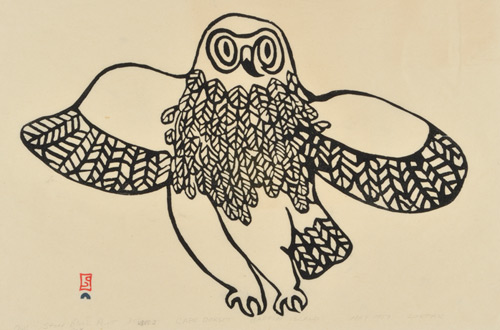

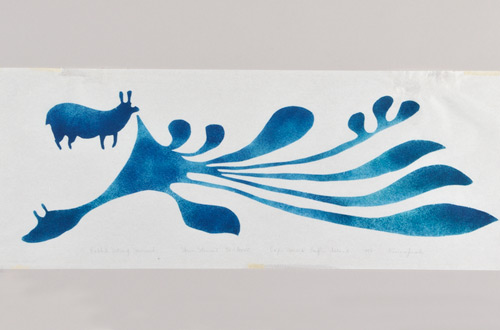

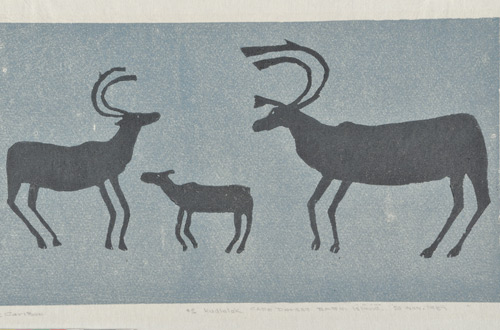

Before 1957, graphic art on paper was rare in the Canadian Eastern Arctic, although individuals such as Noogooshoweetok and Peter Pitseolak created occasional drawings and watercolours when materials were available. Despite the lack of paper, a strong Inuit graphic tradition has existed for many centuries. Incised designs on ivory, stone and musk ox horn — decorative patterns on tools and amulets that evoke the spiritual and animal world —reach back over a thousand years. Appliquéd designs on hide garments and bags sewn by Inuit women evidence an equally vibrant graphic tradition in sealskin and caribou-skin sewing. These traditions continue today using modern and traditional materials.

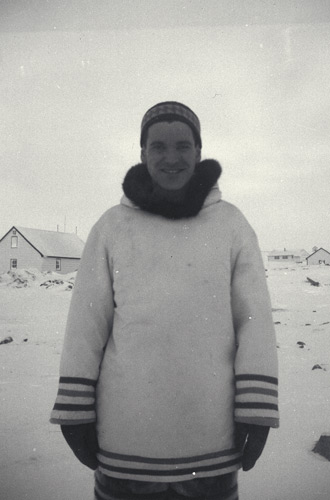

Printmaking was introduced in Cape Dorset in late 1957 by James Houston (1921–2005), an artist, writer and the Area Administrator for South Baffin Island. He was employed by the federal government to encourage the production of carving and crafts in the North and to promote Inuit art in the South. In Cape Dorset’s newly erected crafts shop, Houston along with Osuitok Ipeelee (1922–2005) and Kananginak Pootoogook (1935-2010) began to experiment with fabric and paper printing using linoleum floor tiles cut with simple designs.

The first results looked promising. Osuitok Ipeelee and Kananginak Pootoogook were joined in the print studio by Iyola Kingwatsiak (1933-2000), Lukta Qiatsuk (1928-2004), Eegyvudluk Pootoogook (1931-2000) and translator Joanassie Salomonie (1938-1998). From late 1957 until late 1958, using the few materials available, these resourceful artists continued their experiments and created an uncatalogued, experimental collection of roughly twenty relief and stencil prints on paper. Twelve of these prints were test-marketed through the Hudson’s Bay Company department store in Winnipeg, Manitoba in the fall of 1958, winning rave reviews.

Wanting to bring greater knowledge of printing to the Arctic, James Houston studied printmaking in Japan from November 1958 until February 1959 with the master woodcut printmaker Un’ichi Hiratsuka (1895–1997). Houston returned to Cape Dorset and shared what he had learned in Japan with the Inuit printmakers. Adapting and inventing, the Cape Dorset artists developed their own unique ways of making direct stencil and stonecut relief prints. The Inuit printmakers created their first official catalogued collection of prints in 1959, numbering 41 works in total. These artworks were released to the public with great fanfare in February 1960 at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Meanwhile, to better manage their fledgling studio enterprise, the Cape Dorset artists incorporated a co-operative association called the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, which continues to operate today.