The Origins of the Mercury Series: A Conversation with Managing Editor Pierre M. Desrosiers

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Mercury Series. Published by the Canadian Museum of History in association with the University of Ottawa Press, the Series features pioneering research in the disciplines of Canadian History, Archaeology, Culture and Ethnology.

Covers of Mercury Series books throughout the years.

The Museum recently sat down with Pierre Desrosiers, Managing Editor of the Mercury Series, to discuss its history, evolution and enduring impact.

Shannon Moore: How did you become Managing Editor of the Mercury Series?

Pierre Desrosiers: I was hired in 2019 as the Museum’s Central Archaeology Curator for Quebec and Ontario. At the time, John Willis — former editor of the Mercury Series — was retiring, and I was asked to become the new Managing Editor. I considered it quite an honour.

To someone with my archaeological background, the Series is an exciting collection, featuring so many famous authors and essential works. It is a great responsibility, and I am committed to ensuring the best possible support for the authors who approach us, and the highest standards for scholarly publications.

SM: The Mercury Series is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. Tell us about the origins of the Series, including how and why it was created, and its original purpose.

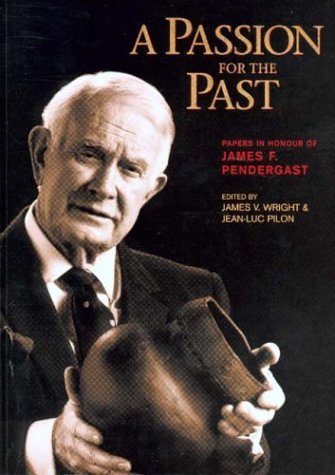

A Passion for the Past

PD: Thanks to a book called A Passion for the Past (2004), we know exactly how the Mercury Series came to be. The book features interviews with James F. Pendergast, a retired lieutenant-colonel and a renowned and prolific archaeologist. In 1972, he was hired as Assistant Director of the National Museum of Man (now the Canadian Museum of History). As soon as he started, he was told by Museum Director William E. Taylor that his “first priority was publications, and he wanted publications quickly.” (Dyke 2004: 30)

The history of serial publications at the Museum probably began with the first Victoria Memorial Museum Bulletin in 1913, which evolved into the National Museum of Canada Bulletin, and even later into the National Museum of Man of the National Museums of Canada Bulletin. There were usually only a few volumes a year, which meant long delays — sometimes years — before a monograph might be published. Taylor wanted to change that by placing an emphasis on speed.

Pendergast rose to the occasion by quickly releasing a series of books, giving each internal branch at the Museum its own sub-collection and colour-coding. Books from the Archaeological Survey of Canada were in orange, Ethnology volumes were in red, and so on. The Mercury Series was born, and books were now being released in rapid succession. Researchers across Canada and around the world could now fill their shelves with books from the Mercury Series.

At this speed, peer review was simply not an option. As you may have guessed, the quality of the printing was also not a priority. Pendergast didn’t want people to comment on the look of the book, but rather on its content, saying, “To hell with the binding. To hell with whether we can spell. We’re passing on knowledge here.” (Dyke 2004: 31)

It comes as no surprise that — following a suggestion from Pendergast’s wife, Margaret — the Series was named after Mercury: a figure from Roman mythology celebrated for his ability to deliver messages at lightning speed — just like Bobby Orr on ice. So, 1972 was not only the year of hockey’s Summit Series, but also the year of the Mercury Series!

By 1982, the Series had more than 100 books to its name, and the Museum was publishing an average of 10 volumes per year.

SM: How has the Mercury Series evolved over time?

PD: Since the 1980s, the world of publishing has changed considerably, particularly with the advent of electronic documents and the Internet. I do not pretend to have all the answers, but I would say that the Mercury Series has been able to constantly adapt to its new environment. In some ways, and in a bow to the speed of production, I would say that it was created like a form of pre-internet. Speed has become less critical over time, and the collection has thus evolved to explore various formats, while also recentring on academic peer review.

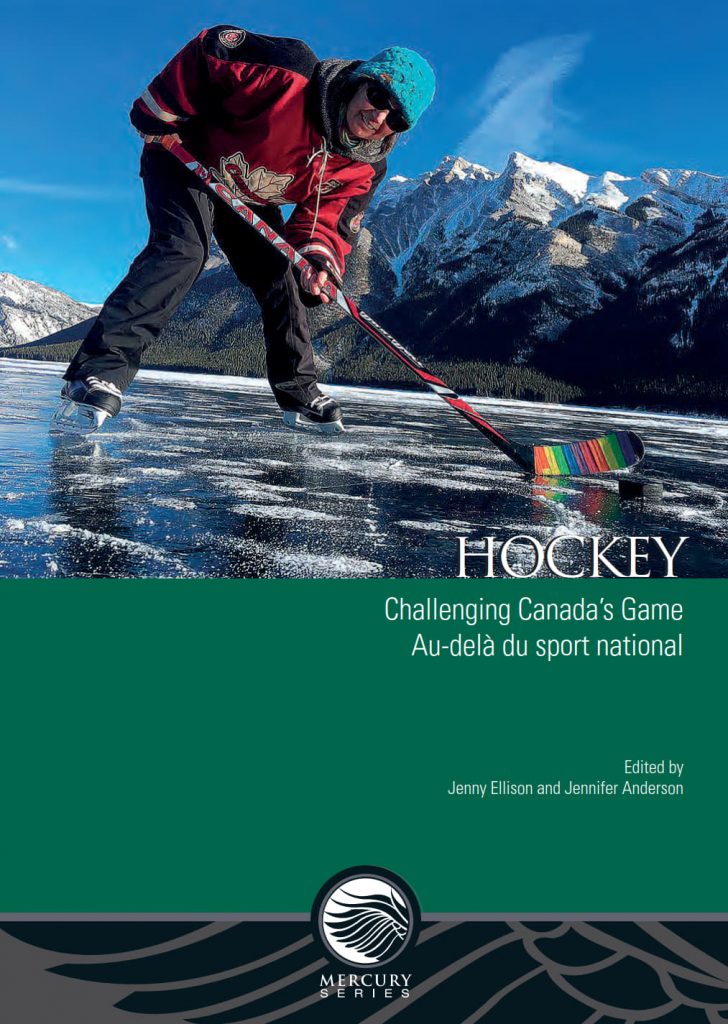

Hockey: Challenging Canada’s Game – Au-delà du sport national

In other words, over the past 50 years, the Series has become a prestigious collection — not only because it includes important books and authors, but also because it has always responded successfully to an evolution in how research is disseminated. This ability to adapt has transformed the collection into a thoughtfully designed, peer-reviewed series of publications.

Also, thanks to our partnership with the University of Ottawa Press, the books are now in full colour with high-resolution images, are offered at a reasonable price, benefit from a large distribution network, and are available in electronic format. And yes, production is still undertaken quickly, in the spirit of the man who founded it.

SM: The Mercury Series is known for its landmark contributions in disciplines pursued at the Canadian Museum of History. What are some of the current trends in the collection?

PD: I recently determined that there are approximately 540 books in the Mercury Series. This is such a large number that it is almost difficult to comprehend.

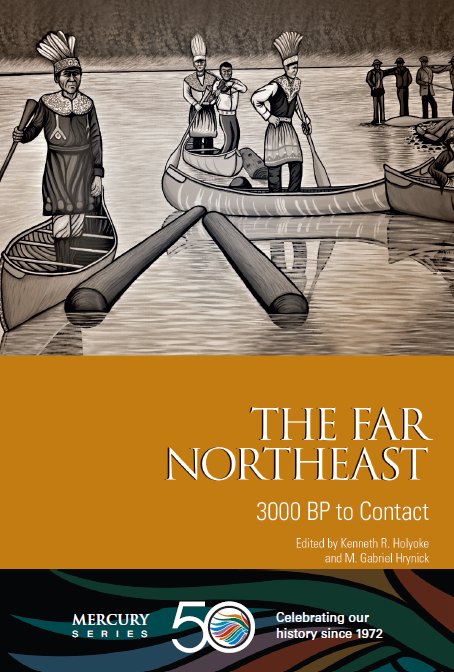

The Far Northeast

The newest book in the Series, The Far Northeast: 3000 BP to Contact (2022), is an outstanding book for this moment in history. Because it concerns the archaeology of Indigenous Peoples of Eastern Canada, it incorporates Indigenous voices — starting with the cover, which was designed by an Indigenous artist.

In general, Archaeology is the most important sub-collection in number, with 181 volumes. This is followed closely by Ethnology, with 146 volumes. More recently, the History sub-collection has clearly been on the rise, with six new volumes within only four years. The most recent book in the History sub-collection — Material Traces of War: Stories of Canadian Women and Conflict, 1914—1945 — is quite exceptional, using material culture to tell numerous stories of women’s contributions to the war effort.

My colleague Gabriel Yanicki, Curator, Western Archaeology, and I recently chaired a session of the Canadian Archaeological Association on the impact of the Mercury Series over the past 50 years. Many volumes are still considered foundational works in their respective areas — such as Threads of Arctic Prehistory: Papers in Honour of William E. Taylor, Jr., which been cited in scholarly works hundreds of times. Alongside History, Archaeology, Culture and Ethnology, sub-collections like Communications and War and Postal have also been part of the Series.

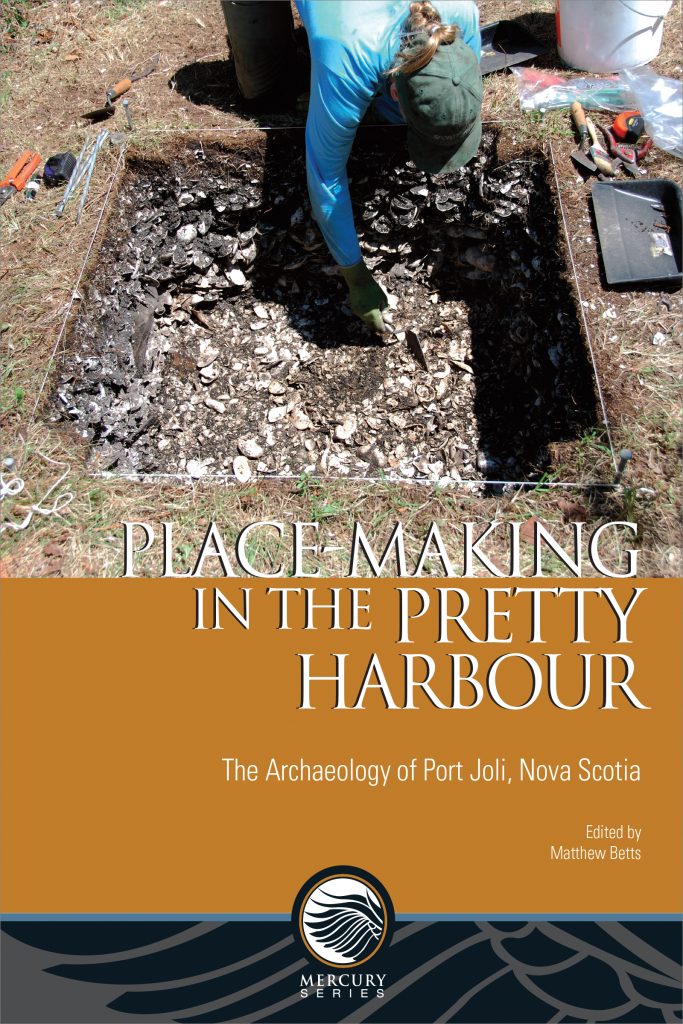

Place-Making in the Pretty Harbour: The Archaeology of Port Joli, Nova Scotia

But the Mercury Series isn’t published just for academic audiences. The impact for descendant communities — that is, people who are directly related to the subject matter— and the broader public is harder to measure. But if you look for print copies of some titles — especially dictionaries and grammars for Indigenous languages (see below) — you’ll find that these can be quite hard to come by. To me, this is a reminder of the enduring value of these works.

As to the future of the collection, we’d like to encourage more submissions by Indigenous authors — perhaps even a volume entirely in an Indigenous language.

To learn more about the Mercury Series, and to purchase books from the collection, visit our online Boutique.

Reference:

- Dyke, Ian (2004). “Private and Public Passions: James Pendergast’s Archaeology and the National Museum of Canada” in A Passion for the Past: Papers in Honour of James F. Pendergast. Edited by J. V. Wright and J.-L. Pilon, pg. 5-48, Mercury Series, Archaeology Paper 164, Canadian Museum of Civilization.

Further Reading:

- Reflections on 1968: An Electrifying Year in Canada

- Honouring an Influential Figure in Historical Geography

- Port of Entry: Immigration Stories From Pier 21

Examples of Dictionaries and Grammars for Indigenous Languages:

- Micmac Dictionary

- A Grammar of Akwesasne Mohawk

- Western Abenaki Dictionary

- Phonology, Dictionary, and Listing of Roots and Lexical Derivates of the Haisla Language of Kitlope and Kitimaat, B.C.

Pierre M. Desrosiers is Managing Editor of the Mercury Series and Curator of Central Archaeology at the Canadian Museum of History.

Shannon Moore is Publications Coordinator and English Language Editor at the Canadian Museum of History and Canadian War Museum.

Mercury Series, celebrating our history, since 1972

The Mercury Series celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2022. Originally produced for quick release, in simple formats with minimal editing, the series has since evolved into a range of thoughtfully designed, peer-reviewed publications. Today, the Mercury Series numbers close to 500 volumes, many of which feature pioneering research in Canadian history, archaeology, culture and ethnology.

The Mercury Series is a co-publication of the Canadian Museum of History and the University of Ottawa Press.