The Road to Responsible Government

Confederation was part of a process that began with rebellion and reform.

During the early and mid-1800s, Crown-appointed members of conservative local elites — known as Tories — monopolized political power in each of the settler colonies. In Upper and Lower Canada (present-day Ontario and Quebec), political reformers — led primarily by lawyers, journalists, and doctors — tried to change the system through peaceful, constitutional means. The failure of these peaceful attempts at reform led to armed rebellions in 1837 and 1838. Government forces crushed these risings: 1,500 people were arrested, 250 deported and 50 hanged.

In 1838, the British government sent Lord Durham to investigate the causes of the rebellions and to recommend reforms. Durham made three recommendations: first, grant greater self-government to Upper and Lower Canada; second, amalgamate the two colonies into one; and third, assimilate Lower Canada’s francophones, who Durham described as “a people with no history and no literature.” The Crown rejected the first recommendation but accepted the second and third. Under the 1840 Act of Union, Upper and Lower Canada were united under a single assembly and government, as the United Province of Canada. English became the sole official language, which infuriated French speakers in both provinces. Under the Act, each side — now called Canada West and Canada East — had an equal number of government representatives. This further angered the (mostly francophone) inhabitants in Canada East, who complained that this left their larger population underrepresented. They demanded “representation by population,” a system that bases the number of government representatives on an area’s population.

Eventually, the reformers won the day through the introduction in 1848 of “responsible government” — a government that is accountable to the people and that depends on the support of an elected assembly. Two politicians, Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine from Canada East and Robert Baldwin from Canada West, put aside their cultural and linguistic differences to form the first government elected by the people. It was through the exercise of responsible government that colonial politicians were able to achieve Confederation two decades later.

The first half of the 19th century saw a huge increase in the settler population. Newcomers laboured to transform the landscape while shaping the political, cultural and social fabric of what would become Canada. As the settler population expanded, Indigenous people were pushed from their ancestral lands to make room for more settlers, left with less influence in matters of trade and negotiation, and lost the ally status they had held at the beginning of the 1800s. European settlers, for the most part, saw themselves as culturally and racially superior to Indigenous people and believed that Indigenous cultures were destined to die out. This belief informed racist policies aimed at dominating and assimilating Indigenous people and making way for the expansion of European settlement and culture. Consequently, Indigenous people were not a part of the vision for Confederation. Indigenous communities were not consulted, nor were their opinions taken into consideration during the debates and discussions leading up to Confederation.

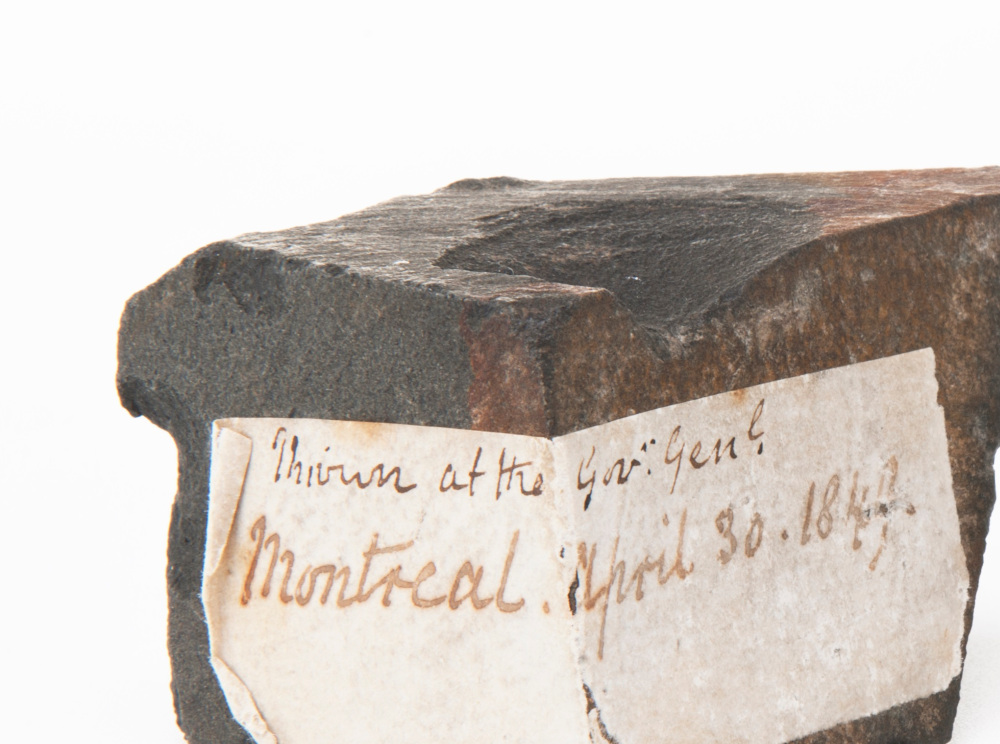

Learn more about the controversial idea of responsible government through a political cartoon, the burning of the Montréal legislature and the stoning of a Governor General.