From Charlottetown to London

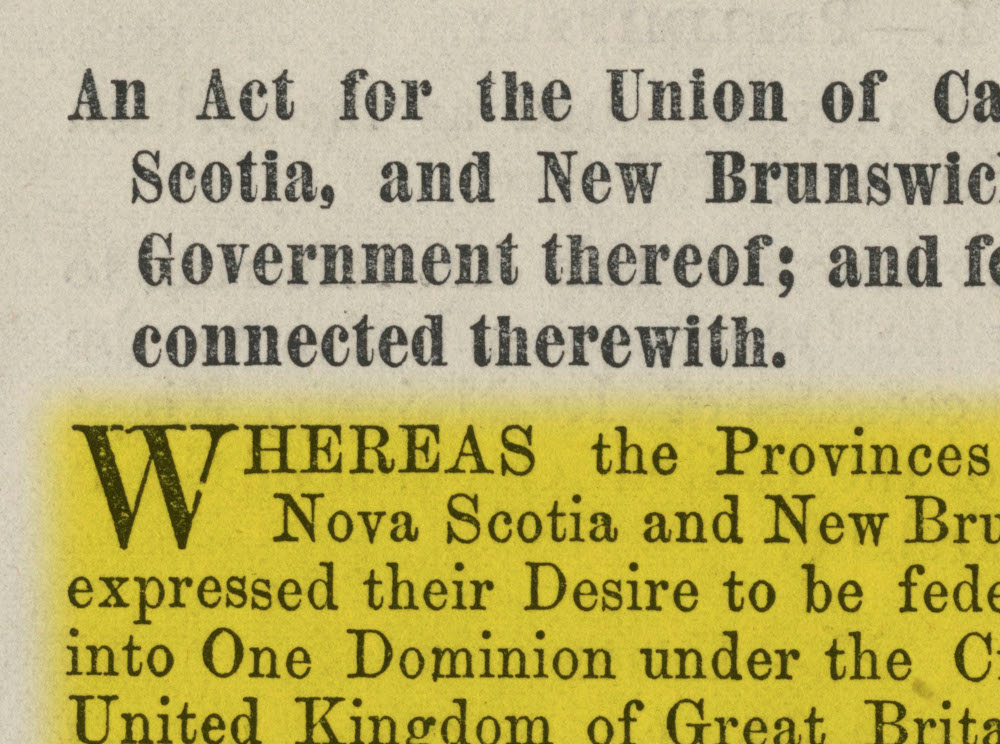

The year 1867 is often cited as the year that Canada became a country. However, in reality, Canada changed and evolved over time to become the country we know today, and will continue to evolve in the future. Many different people, events and laws have influenced progress in Canada; for example, the Statute of Westminster of 1931 and the Constitution Act of 1982 are both critical laws that helped Canada gain independence from Britain.

Confederation was achieved through a process of discussion and debate, much of which took place during three important conferences:

- At the Charlottetown Conference in 1864, colonial representatives discussed and agreed, in principle, to the concept of Confederation.

- At the Québec Conference in 1864, colonial representatives worked out the details and drafted a Confederation blueprint that proposed how each of the provinces would be represented in the legislature.

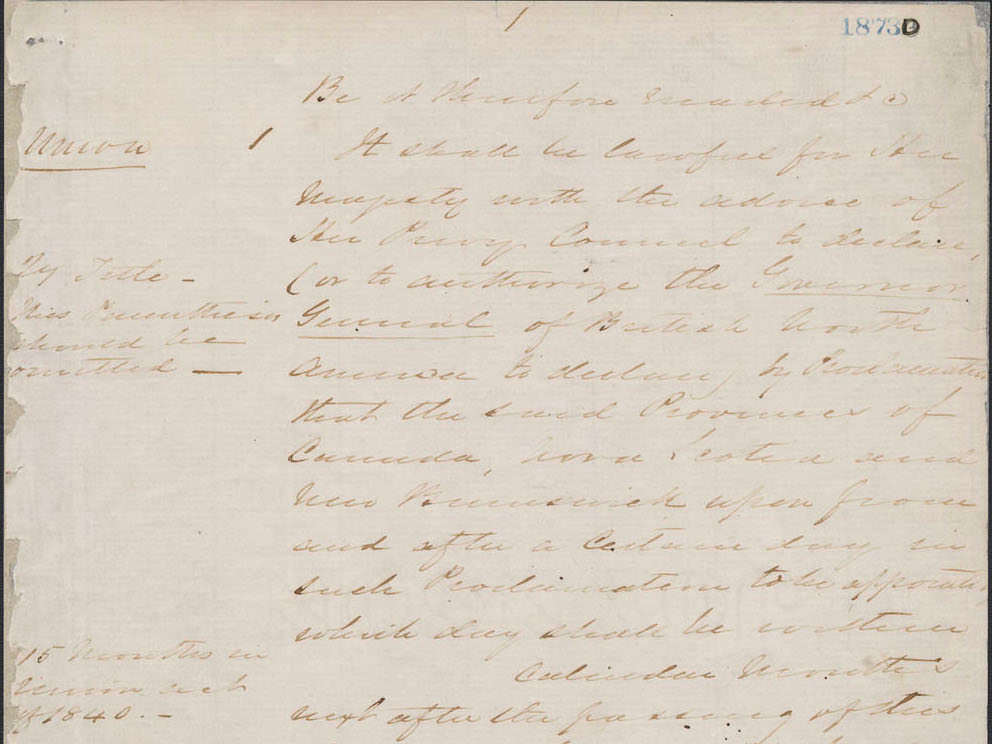

- At the London Conference in 1866–1867, colonial representatives and imperial government officials reviewed, amended and transformed the Confederation blueprint into constitutional form, and planned how to see the resulting bill through both Houses of the British Parliament.

During these conferences, the delegates debated the merits and drawbacks of Confederation. Each colony had differing opinions on the best way to move forward. Supporters saw three important advantages to Confederation. First, the colonies would be able to defend themselves more effectively if they were united. Threats from the Americans, particularly during the American Civil War (1861–1865) had created security fears. Second, a union would make trade between the colonies easier and more profitable. Third, Confederation would end the political deadlock in the United Province of Canada by separating Canada East and Canada West into two distinct provinces — Quebec and Ontario, respectively — and giving each its own legislature with jurisdiction over local matters such as health care and education.

For those who argued against Confederation, the main concerns were that French speakers’ rights to their own language, culture and institutions would not be adequately represented under a large union. Other concerns came from those in smaller Maritime colonies who, similarly, feared that their voices and identities would be lost once they became part of Canada.

Four colonies were represented at the Charlottetown Conference: Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and the United Province of Canada (present-day Quebec and Ontario). The delegates sent to represent their colonies were all male, and all white.

Explore the push to Confederation through the Charlottetown Conference, the British North America Act and the Dominion of Canada’s controversial first prime minister: Sir John A. Macdonald.