Historic Ivories at the Canadian Museum of Civilization – Page 1

“A FEW THINGS IN THE WAY OF CURIOS”, HISTORIC IVORIES AT THE CANADIAN MUSEUM OF CIVILIZATION

Maria Von Finckenstein

Curator of Inuit Art

Canadian Ethnology Service

Canadian Museum of Civilization

This essay was originally published in Inuit Art Quarterly, vol.14, no.4 (Winter 1999), with revisions by the author in March 2001. Reproduced by permission.

Applied to Inuit art, the term “historic” serves to distinguish the period between roughly 1750 and 1948. It’s the era between first sustained contact between Inuit and visitors to the North (which varied according to region) and the beginning of the commercial artform, which started in 1948 with James Houston’s first trip to Inukjuak. The Canadian Museum of Civilization (CMC) owns approximately 360 carvings that stem from this period.

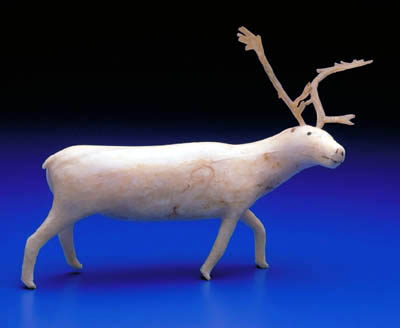

Caribou with antlers, 1903-04

Collected by A.P. Low at Cape Fullerton, Hudson Bay (ivory, black colouring and muskox horn; 4.2 x 0.8 x 0.8 in. Canadian Museum of Civilization IV-B-799). PCD 94-733-002

This is one of the “two caribou with antlers” listed among the group of ivory carvings transferred to the CMC in 1962. A.P. Low must surely have had the creator of this piece in mind when he said that “occasionally there arises a real artist.” The turning of the head, as if the animal were startled by something, shows an acute power of observation.

This body of work created over roughly two centuries has received scant attention from researchers. Jean Blodgett (1979) and Bernadette Driscoll (1988) have both written general overviews of the period, while Charles Martijn has quoted various explorers’ comments about art making in different areas, without going into any detail about local or regional styles (Martijn, 1964). Jane Sproull Thompson, in her important article “A Tiny Arctic World”, filled in the picture for the second half of the 19th century in Labrador, where there was a distinctive tradition of creating little ivory miniatures reflecting details of everyday camp life (Thomson, 1992).

Man stalking seal, 1903-04

Collected by A.P. Low at Cape Fullerton, Hudson Bay (ivory, 0.9 x 2.5 x 1.1 in Canadian Museum of Civilization IV-B-783) PCD 94-854-016

In his account of the expedition, Low describes the stalking of seal: “A seal appears to sleep in short naps, and raises his head every few minutes; when he does so the hunter immediately hides his face, and with his arms and legs imitates the motions of a seal scratching and lazily rolling, at the same time mimicking the blowing and other noises made by the seal; by so doing he soon lulls suspicion, and is enabled to crawl a little closer” (1906, 153).

I will try here to add another piece to the puzzle. The CMC owns a set of ivory carvings that were collected by A.P. Low and the surgeon L.E. Borden, both of whom participated in a government expedition on the Neptune in 1903-04. The purpose of the expedition was to survey the areas around Southampton Island and to establish a customs office at Port Burwell, where ships entering or leaving Hudson Bay were to report from then on. Previously, American and Scottish whalers had been hunting in Canadian waters without any impediment. The expedition constituted an important step towards establishing the Canadian claim to the Arctic.

During the expedition both Low and Borden collected ivory carvings. So far, those donated by A.P. Low (cat.# IV-B-768 – IV-B-818) have been dated to circa 1880-1890, under the assumption that they were collected by Low on one of his former expeditions to Labrador. I am convinced, however, they were collected during the Neptune expedition. They were transferred to the CMC in 1962 but no provenance was given at that time.

Polar bear, 1903-04

Collected by L.E. Borden at Cape Fullerton,Hudson Bay (ivory and black colouring, 1.2 x 0.6 x 2.3 in. Canadian Museum of Civilization IV-X-563) PCD 94-594-084

The realism of this piece, with different positions for each of the legs and a slight turn of the head, makes this bear from Borden’s collection very similar to the muskox and caribou from Low’s collection.

The Low family deposited this collection of carvings at the Public Archives in 1943. Unfortunately, no detailed listing exists in the Archives’ records although there is one “list of material presented to the Public Archives by Miss Estelle Low” among the gift correspondence from 1943. The second item on this list laconically refers to “miscellaneous lot of carved articles and a beaded bag made by the Eskimos of Labrador.” Obviously Miss Estelle Low, daughter of Albert P. Low, did not know any specifics about the provenance of the ivory carvings when she donated them to the Public Archives.

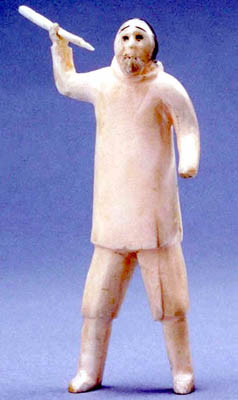

Standing hunter with rifle, 1903-04

collected by Albert P. Low at Cape Fullerton, Hudson Bay (ivory and black colouring; 2.6 x 2.7 x 0.8 in. Canadian Museum of Civilization IV-B-781) PCD 94-854-017

This carving was included in the 1970 Masterworks exhibition organized by the Eskimo Arts Council and the Canadian Museum of Civilization. The masterful rendering of the hunched shoulder and the hunter’s body turned sideways point to the same provenance as that of Caribou with antlers. The black colouring is typical, the artist most likely using soot from the seal-oil lamp or dirt

Borden, who died in 1963, made a bequest in his will of “all his Esquimo Walrus Carvings and all his diaries and notebooks concerning the Arctic region, for use in the Government of Canada Archives” (Davies, 1963). Again, no list survives to enlighten us as to where the pieces were collected.

In 1964, the Dominion Archivist, one Dr. Lamb, expressed his delight at uniting the two collections of carvings. He wrote to Borden’s widow:

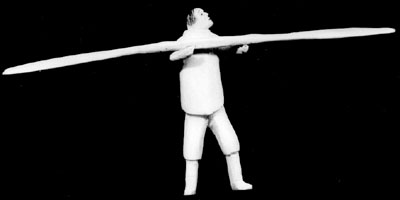

Standing hunter with harpoon 1903-04

collected by A.P. Low at Cape Fullerton, Hudson Bay (ivory and black colouring; 3 x 2.7 x 0.8 in. harpoon 2.5 in.

Canadian Museum of Civilization IV-B-782) PCD 95-405-045

With all the weight on his left leg, the hunter is bent forward, totally absorbed in the task of throwing the harpoon at just the right moment.

“I think I told Dr. Borden and yourself that the Low family gave to the Archives, a good many years ago, the collection of carvings that Mr. Low had gathered in the course of his famous expedition. These were transferred to the National Museum a couple of years ago. They resemble and complement Dr. Borden’s collection in many ways, and I am very glad that the two have been brought together.”

(Lamb, 1964; my italics)

The date of Borden’s pieces is easy to establish. The Neptune cruise was the only expedition in which he ever participated, so there is no doubt that his collection dates from 1903-04. As Dr. Lamb correctly noticed, there is a great stylistic resemblance between the carvings from both collections. Hence it is fairly safe to assume that A.P. Low’s ivory carvings also stem from 1903/04.

Historic Ivories at the Canadian Museum of Civilization – Page 2

(continued)

Standing man with paddle, 1903-04

collected by A.P. Low at Cape Fullerton, Hudson Bay (ivory and black colouring; 5.4 x 2.8 x 1.9 in.; Canadian Museum of Civilization IV-B-784 A-B).

This figure is perfectly balanced and stands without any support. Ivory allows the carver to incise incredibly fine facial features. Black ink emphasizes the eyes and mouth.

Having established a firm date – the date of the cruise – does not necessarily tell us much about their provenance. Although the cruise has been well documented, there is tantalizingly little mention of any ivory carvings. It is frustrating for the contemporary researcher that both men, Low as a geologist and Borden as a medical doctor, paid very little attention to what they considered mere curios.

In the account of the expedition, entitled “The Cruise of the Neptune”, A.P. Low mentions ivory carvings in one paragraph. “The carving of walrus ivory passes many an hour of the long winter.

Standing man with ice-scoop, 1903-04

collected by A.P. Low at Cape Fullerton, Hudson Bay (ivory and black colouring; 2 x 1.8 x 0.5 in.; Canadian Museum of Civilization IV-B-774).

The ice-scoop was used to remove snow covering a seal’s breathing hole

As a rule the carvings are crude representations of various animals and other animate objects, and have no high value as objects of art, but occasionally there arises a real artist, who when encouraged will produce wonderfully artistic models of the various animals, men, dogsleds and almost anything suggested to him” (p.176). As we know that the Neptune wintered in Cape Fullerton – and ivory carvings were mostly done during the long hours of winter – it seems safe to assume that these were done by Inuit from the area around Cape Fullerton.

There is corroboration for this assumption from another source. During the winter of 1903-04 the Neptune was stationed very close to the Era, an American whaling ship commanded by Captain George Comer. In his diaries Comer makes several references to Commander Low and his ship’s doctor. The entry for Thursday, April 21, 1904 reads as follows: “Commander Low and the doctor were over. I gave them some ivory carvings to take home to friends” (Ross, 1984, p.111). On January 20, 1904 he mentions “my chief native Harry (Teseuke) has been making some ivory carvings for Commander Low, which he took over this evening” (Ross, 1984, p.90).

Harry, Chief of the Aivilingmiut, 1903-04

photo by A.P. Low (National Archives of Canada PA-050919).

According to Captain Comer, his mate Harry Teseuke made a series of ivory carvings for Commander Low. In addition, one of the ivory bears in Borden’s collection is signed “Harry”. Ethel Borden tells the following anecdote about Harry and Dr. Borden: “A woman had a sore leg, another had hemiplegia, yet another was totally blind for years with cataracts in both eyes. The doctor drew a diagram and within two weeks, Harry, an Eskimo genius, carved and polished two ivory spuds which were made successfully under the most primitive conditions”

(Borden 1961, 35).

The latter passage relates directly to an entry by Borden who, in his diary of the cruise, mentions once briefly: “Harry, native, made me a few figures from ivory.” (entry from January 12, 1904). Harry was the chief of the Aivilingmiut and Comer’s “head native.” One of the carvings in Borden’s collection is actually signed “Harry”.

Man with rifle, crawling on his belly, 1903-04

collected by L.E. Borden at Cape Fullerton, Hudson Bay (ivory and black colouring; 0.7 x 0.6 x 3 in., rifle 2 in. long; Canadian Museum of Civilization IV-X-559).

This figure, collected by Borden, may not be by the same hand as the hunters from the Low collection, but it is very similar in style. The stylized, small-hooded parka, the fine lines used to indicate hair and the attempt to capture movement reflect the same distinct local style.

Whether Harry incised the signature himself we will never know. In another place Borden comments about Captain Comer: “Although peculiar in many respects, he is a very good hearted man and altogether I have fared pretty well at his hands, having received before some carved ivory and a few things in the way of curios” (entry from May 17,1904). In addition there is mention in a memo from his wife, Ethel Borden, of “carvings and artifacts received as appreciation of care of Eskimo.” So this meagre information, in total, reveals that the artifacts in Borden’s collection were partially made by “Harry,” as well as by grateful patients. From A.P. Low’s comments one can deduce that he made suggestions regarding themes to Inuit whom he considered endowed with artistic talent. The themes for the group of seven figures, engaged in various activities related to the hunt, may have been suggested by him; these figures are most likely by Harry, Comer’s main assistant.

Muskox, 1903-04

collected by A.P. Low at Cape Fullerton, Hudson Bay (ivory, bone and muskox horn; 1.9 x 0.6 x 2.8 in.; Canadian Museum of Civilization IV-B-804).

The positioning of the legs, the lowered neck to indicate grazing, and the slight turn of the head imbue this little sculpture with life.

In style these miniatures differ from those from Labrador. They have none of the elaborate red and black markings on parka decorations that are such a distinctive feature of Labrador ivories from the late 19th century. They are generally larger and there is a noticeable attempt to capture movement and gestures. They are similar to Labrador ivories, however, in the use of some black colouring to indicate hair and facial features. This technique carried over into early miniatures from the contemporary period, especially in the work of artists like Sheokjuk Oqutaq and Peesee Oshuitoq from Cape Dorset.

Franz Boas, in one comment, refers specifically to this area around Southampton Island and the west coast of Hudson Bay: “the Aivilik and Kinipetu of Southampton Island make a great many carvings in ivory and soapstone” (1901, p.113).

Hunter with spear, 1903-04

Collected by L.E. Borden at Cape Fullerton, Hudson Bay (ivory and black colouring; 3.2 x 1.4 x 0.6 in. Canadian Museum of Civilization IV-X- 575) PCD 95-400-067

I agree with Martijn’s assumption that employment with whalers such as Captain Comer or explorers such as A.P. Low and Dr. Borden probably led to an increase in carving in response to the demand of the ships’ crews to purchase “keepsakes”, as Martijn calls them, to take home after a successful hunt (1964, p.556).

Thus it becomes clear that Inuit, certainly from this region of the eastern Arctic, were accustomed to producing souvenirs for an outside culture long before 1948. When Houston travelled across the Arctic encouraging people to carve, he continued a tradition that had started with the first contact between the Inuit and intruders into their world.

Bear, 1903-04

collected by L.E. Borden at Cape Fullerton, Hudson Bay (ivory and black colouring 3 x 1.5 x 7 cm; Canadian Museum of Civilization IV-X-551). PCD 94-594-049

As the only piece that is actually signed with the name, “Harry”, this bear is crucial in identifying what other ivories stem from Harry’s gifted hands. The sensitivity and elegance of this little piece make it very likely that the “Caribou with Antlers” (IV-B-799) and the series of hunting figures from A.P. Low’s collection were also done by Harry, the genius.

Among the long list of explorers, whalers, missionaries, traders, scientists, anthropologists, RCMP officers, and government officials were A.P. Low and Dr. Borden, who received the group of carvings shown here both as gifts and as private commissions.

The next step in research would be to study the 30 ivory carvings which Captain Comer collected between 1902 and 1910 for the American Museum of Natural History, upon the request of Franz Boas, ethnologist at that institution.

Historic Ivories at the Canadian Museum of Civilization – Page 3

Acknowledgement:

I would like to thank Bernadette Driscoll who, in a letter to Odette Leroux, former curator of Inuit art at CMC, pointed out the similarity between some of the ivory carvings Comer had collected for Boas and the carvings in the CMC’s collection. She made the connection that the Era and the Neptune had wintered beside each other in 1903/04, which introduced a new line of enquiry, the result of which is this essay.

Bibliography:

- Blodgett, Jean

1979 “The Historic Period in Inuit Art,” Beaver, vol.310, no.1 (Summer), 17-27.

- Boas, Franz

1901 “The Eskimo of Baffin Land and Hudson Bay,” Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, vol.15, part 1, 113.

- Borden, K. Ethel

1961 “Northward 1903-04,” Canadian Geographic Journal, vol.50, no.1 (January), 32-39.

- Borden, Lorris Elijah

1904 “The lost Expedition”. Unpublished diary. National Archives of Canada: MG 30, vol.1-3.

- Driscoll, Bernadette

1988 “Zwischen Konvention und Innovation: die historische Periode der Inuit-Kunst 1800-1950,” in Zeitgenoessische Kunst der Indianer und Eskimos in Kanada, ed. Gerhard Hoffmann. Stuttgart: Cantz Verlag.

- Lamb, Kaye

1964 Letter to Mrs. L.E. Borden, July 8

- Low, A. P.

1906 The Cruise of the Neptune: Report on the Dominion Government Expedition to Hudson Bay and the Arctic Islands 1903-1904. Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau.

- Martijn, Charles A.

1964 “Canadian Eskimo Carving in Historical Perspective,” in Anthropos, vol.59, 546-596.

- Ross, W. Gillies, ed.

1984 An Arctic Whaling Diary: The Journal of Captain George Comer in Hudson Bay 1903-1905. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Thomson, Jane Sproull

1992 “A Tiny Arctic World,” in Inuit Art Quarterly, vol.7, no 4, 14-23.