The name of our country, and the identity of those who live within it, has a story that is at once remarkable, amusing, and deeply fitting.

In 1535, when French explorer Jacques Cartier sailed into the gulf of the St. Lawrence, he heard from his Indigenous guides a word that he transcribed as “Canada.” For them, the term meant “town,” “village” or “settlement.” They were specifically directing him toward Stadaconé, where Québec City stands today. The explorer, however, seized upon the word not merely as a reference to one particular town but as a label for the wider region and its people. He referred to them as Canadiens and Canadians. This moment was recreated, with an added touch of humour, in a 1991 Heritage Minute.

From that encounter grew a name that, centuries later, would come to represent an entire nation. Pondering what it means to be Canadian, from the vantage point of Early Canadian history, invites us to acknowledge this tangled origin story. Like the country itself, the term “Canada” began in confusion. Born of cross-cultural miscommunication, reshaped by colonial encounters, it has been continually redefined. To reflect on the word is to confront a history marked by ambiguity, appropriation, reinterpretation and transformation.

The colonial act of naming

In reality, Cartier was likely not the first European to hear or even use the name. Fishermen and whalers from Spain, Portugal, France and Britain had been frequenting the waters of the St. Lawrence before his voyages. Cartier, moreover, seems to have understood that the term was used in a more specific sense. In the linguistic notes that conclude his travel narrative, he explicitly recorded that “they call a town Canada.” And yet he did use it to broadly refer to the land and its first peoples, and the seed of a national name and identity took root.

The two young Indigenous men who acted as Cartier’s guides in 1535, Taignoagny and Domagaya, had been captured by him during his earlier voyage. While Cartier and his crew are often remembered for their courage as explorers, they were also unmistakably agents of colonization — kidnapping locals, showing little regard for cultural differences, and imposing names on places and peoples. Thus, the origin of the name “Canada” reminds us of the entanglement of curiosity and conquest, of discovery mixed with cruelty.

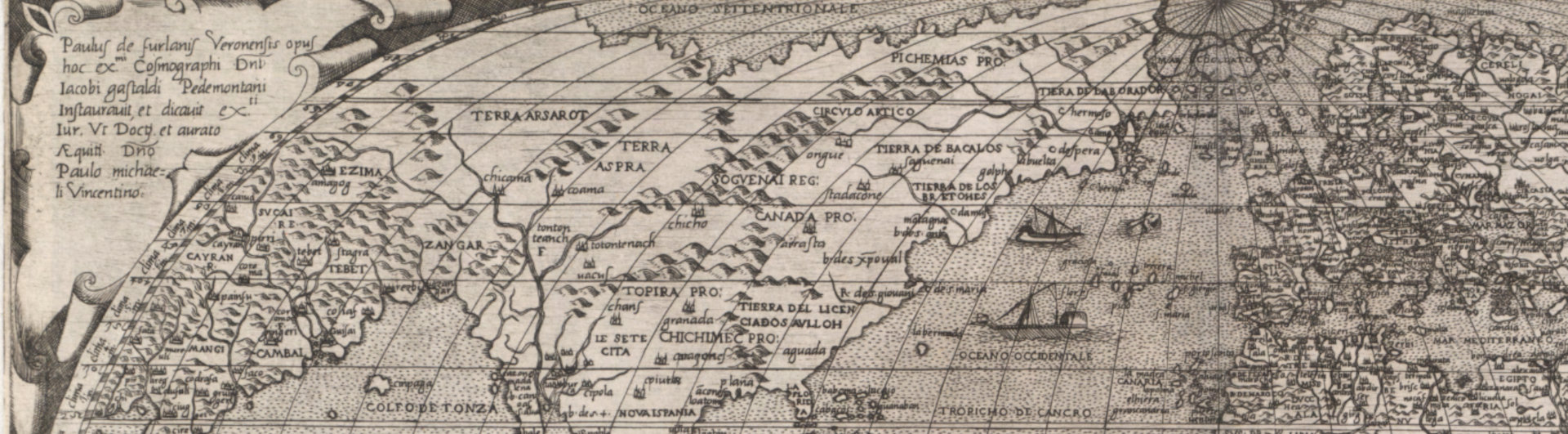

Detail from a 1560 map by Italian cartographer Paolo Forlani. Forlani was the first to include the name “Canada” on a printed map.

Library and Archives Canada, G3200 1560.F67 H3

From Indigenous to French, and from French to British

By the early 17th century, tragedy had reshaped the region. The original inhabitants whom Cartier had called “Canadians” and whom archaeologists refer to as St. Lawrence Iroquoians, had dispersed away owing to epidemics, climate change, and warfare. Variants of “kanata,” still meaning “village,” endure in the Mohawk and Wendat languages to this day. This should be a reminder of the fact that interconnected Indigenous societies and cultures persist despite colonial disruption.

Samuel de Champlain and his contemporaries, meanwhile, applied the word Canadien not to the St. Lawrence Iroquoian’s descendants, but to the culturally unrelated Mi’kmaq of Gaspé. Such misapplications were typical of European explorers, who often transferred Indigenous names indiscriminately to new landscapes or peoples.

Then, the meaning of Canadien shifted once more. By the mid-17th century, French settlers themselves had begun to adopt the name. At first, it functioned merely as a geographic adjective: Canadian land, Canadian climate, Canadian products. But gradually, it evolved into an identity marker. A Canadien was now a French colonist born in the colony, or a long-term resident, distinct from newcomers arriving from France. A new sense of belonging was taking shape, rooted in the realities of colonial life. This appropriation of the name coincided with its abandonment as a label for Indigenous groups.

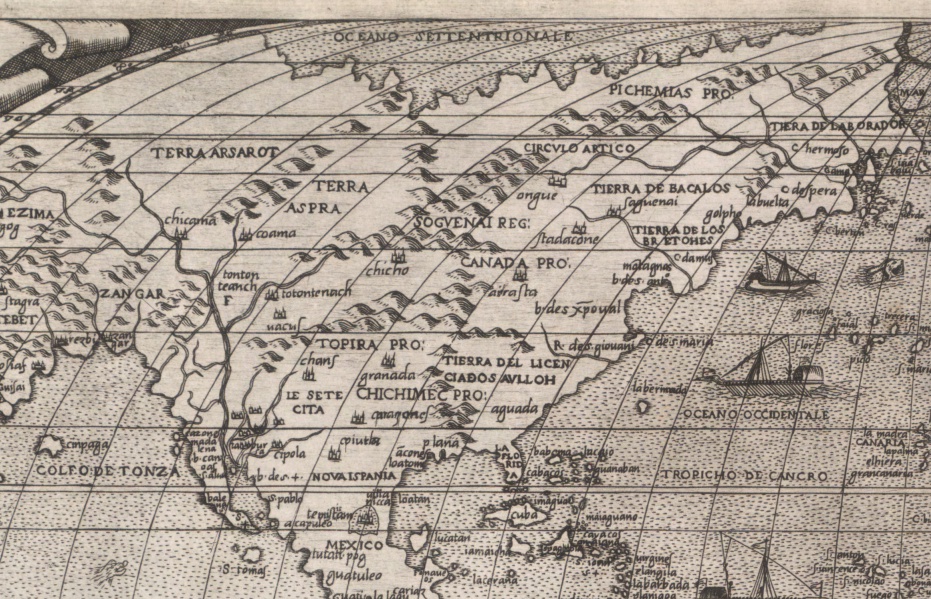

An engraving titled “Canadien en raquette allant en guerre sur la neige” from Bacqueville de la Potherie’s Histoire de I’Amérique septentrionale, 1703.

The geographic scope of “Canada” expanded. French fur traders and explorers carried the name westward into the Great Lakes and down the Mississippi River, so that by the early 18th century, “Canada” could designate a vast territory. Yet the heart of Canada — its cultural and demographic centre — remained the St. Lawrence valley.

The British conquest of New France in 1763 would bring about further shifts. In 1791, the British divided what they had previously called the Province of Quebec into Lower Canada (largely French-speaking) and Upper Canada (largely English-speaking). Later, in 1841, these were reunited as the Province of Canada. Through these transformations, French speakers continued to refer to themselves as Canadiens and be called Canadians by British settlers, who were not quick to adopt the name themselves. But gradually, by the mid-19th century, English colonists had appropriated it in turn.

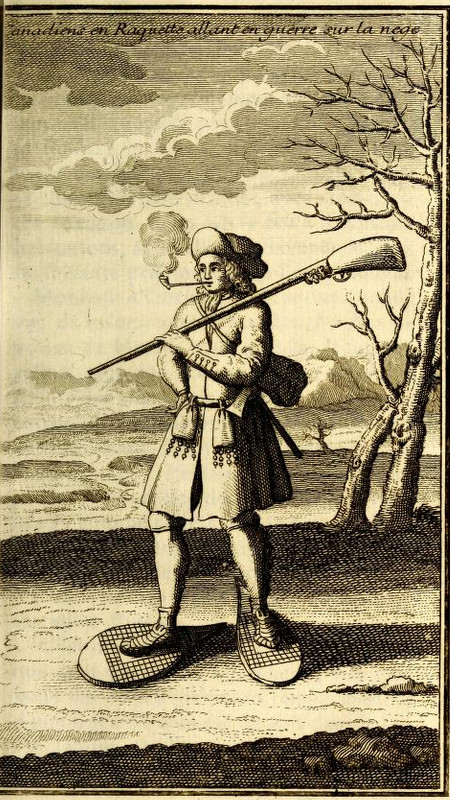

The three-penny beaver was the first stamp to use the name “Canada.” It was issued in 1851, when the British Crown empowered the Province of Canada to manage its own postal system.

Postal Museum, Canadian Museum of History, 2002.87

Resisting the label

As Confederation approached in 1867, the search for a national name was far from settled. Alternatives abounded, ranging from the fanciful (Borealia, Victorialand) to the historically rooted (Hochelaga). Ultimately, Canada prevailed, but not everyone welcomed it. In the Maritime provinces — Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island — many resisted the term, seeing it as something that belonged to central provinces like Ontario and Quebec rather than to themselves. The Canadians were “from away.”

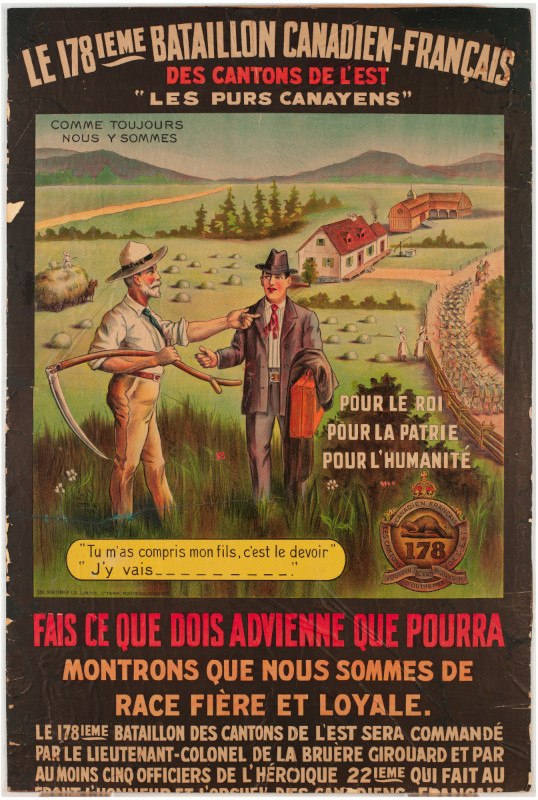

This First World War recruitment poster is targeted at Quebecers from the Eastern Townships and calls them to action in the name of a collective Canadian identity.

Canadian War Museum, 19900076-821

During the First World War, recruiters appealed to Canadians as separate from yet connected to Britain, but also as neighbours and compatriots of the United States.

Canadian War Museum, 19900055-002

In the 20th century, new tensions emerged and names evolved accordingly. The Quiet Revolution of the 1960s in Quebec redefined French-Canadian identity along provincial lines. “Canadien français” gave way to “Québécois,” while other provincial alternatives like Franco-Ontarian and Franco-Manitoban arose, as many francophones explicitly rejected Canada as a federal project that failed to represent them. In parallel, Indigenous Peoples increasingly asserted their sovereignty by refusing the label “Canadian.” For many, to call oneself an Indigenous Canadian was to accept a colonial framework imposed by a state that had long denied them citizenship and continues to challenge their rights. Many today prefer to describe themselves as Indigenous people living in Canada, not of Canada.

At the same time, immigration transformed the meaning of Canadian. Newcomers from Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East embraced the name, weaving it into their own identities and adding new cultural threads to the national tapestry. Today, being Canadian is as much about plurality, diversity, and the tensions and contradictions of belonging as it is about depth of shared historical experience.

A name in motion

That Canada — a vast country defined by cultural multiplicity — should take its name from a misunderstanding is profoundly fitting. From its very beginnings, “Canada” has never meant just one thing. It has described attachment to the land and, equally, negotiation and debate over whose land it is.

From a single town on the St. Lawrence, the name grew into a nation-state, and from a misunderstanding emerged a powerful symbol of belonging. But it remains a name in motion, continually shaped and reshaped by the people who claim it, reject it, or redefine it. To be Canadian is, and always has been, to live in the space between meanings — where history, culture and identity meet, clash and evolve.

Elizabeth Manley’s Team Canada jacket from the 1988 Winter Olympic Games. Canada’s red-and-white maple leaf imagery are now instantly recognizable, but what “Canada” means and who “Canadians” are has a complicated history.

Canadian Museum of History, IMG2024-0122-0025-Dm

Jean-François Lozier

Jean-François Lozier has been Curator of French North American history at the Museum since 2011. His research focuses primarily on French-Indigenous relations during the 17th and 18th centuries, Early Canadian material culture in all its forms, and memory and commemoration of this period.

Read full bio of Jean-François Lozier