With royal officials in control, New France became more than a fur-trade outpost. French women arrived in large numbers, and farms and families flourished.

King Louis XIV and his chief minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert gave New France a government similar to that of a French province. In New France — unlike France — there were no powerful local leaders to compete with the royal administration.

On paper, New France was a model of absolutist rule. But in practice, colonists enjoyed more prosperity and independence than their counterparts in France.

Three officials, the governor general, the intendant and the bishop of Québec, administered the colony on the king’s behalf. All three served on the sovereign council — the colony’s highest court.

To encourage settlement, the government rewarded prominent subjects with large land grants. These new seigneurs, or lords, granted portions of their lands to settlers, called habitants, in return for annual payments. The government also offered habitants incentives to marry and start families.

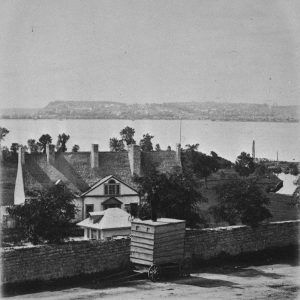

The governor general was the highest-ranking official in New France. His palace, the Château Saint-Louis, was the colony’s social centre. His main responsibilities were the colony’s defence and managing relations with First Nations.

The Civil Administrator

The intendant managed the colony’s internal affairs, including justice, currency, finance, agriculture and trade. The office was as powerful as the governor general’s, but not as prestigious.

The Spiritual Leader

The Church functioned as an arm of the state, running schools, hospitals and charities. The bishop sometimes disagreed with civil officials and with habitants who resisted religious taxes, or tithes.

The Seigneurs

New France’s system of land ownership rewarded loyalty and encouraged settlement. The first seigneurial grant, to surgeon Robert Giffard in 1634, was awarded in Beauport, near Québec City. Later grantees included military officers, civil servants and religious institutions. In theory, annual fees from habitants would support the seigneur. In practice, the fees, paid in cash or in kind, were very modest. In the 1600s, some seigneurs were not much better off than their habitants.

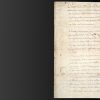

Relic of the First Seigneur

The inscription on this lead plaque from the manor house at Beauport commemorates the grant of the seigneury to Robert Giffard in 1634.

Inscription:

“IHS MIA LAN 1634 LE 25 IUILLET IE AI ÉTÉ PLANTE PREMIERE P C GIFFARD SEIGNEUR DE CE LIEU”

IHS MIA (Iesu Mariae Immaculatae Auspice, Under the protection of Jesus and Mary Immaculate). In the year 1634, July 25th, I was laid first P.C. Giffard, Seigneur of this place. (The abbreviation P.C. remains a mystery.)

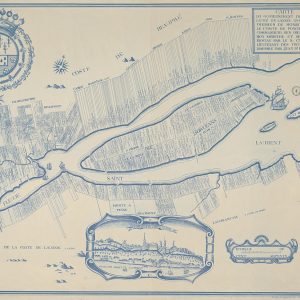

A Landscape of Rectangles

If you fly over the St. Lawrence Valley, you will notice long, narrow lots fronting on the riverbank or the roads running parallel to the river. This pattern ensured that early settlers had access to the water. The surveyors who laid out these lots in the 1600s and 1700s used the French units of measurement of the time. For this reason, old French measurements are still legal in Canada when describing lands once under seigneurial tenure.

The Canadian Nobility

The king rewarded loyalty with honours or noble status. A man might receive an officer’s commission, the Croix de Saint Louis or a patent of nobility for his services in Canada. In 1700, King Louis XIV made Charles Le Moyne a baron. The title recognized Le Moyne’s military service in countering the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), and his work in developing his seigneury at Longueuil, near Montréal. His family played a key role throughout the French regime.

“Those [in Canada] who had been awarded the Croix de Saint Louis were as highly esteemed as lieutenant-generals and Knights of the Holy Spirit in France.”

Pierre Pouchot, military officer, 1755

Learn more

Photo at top of page:

Seigneurial grants near Québec City

From Gédéon de Catalogne, Map of the Government of Québec, 1709

Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, G/3451/G46/1709/C3 81/1921/DCA

Resource

Resource

Book

Book

Archives

Archives