May is Asian Heritage Month, a time to reflect on the contributions made by Canadians of Asian heritage to Canada, often in the face of discrimination. The new Canadian History Hall offers important insights into the complex story of Canada’s growing ethnic diversity in the 20th century.

One of the important threads in the Hall’s third gallery — Modern Canada — is how political and social struggle, along with changing social norms, helped to broaden rights and social inclusion over the last century. The challenge of negotiating differences remains a constant in Canada today. And the experiences and voices of Asian Canadians offer powerful perspectives on this theme.

In the first half of the 20th century, Canada was not, in many ways, an inclusive or tolerant society. This was reflected in our country’s immigration policy and in social attitudes toward ethnic and other minorities in the early 1900s. The story of the Komagata Maru — a ship carrying predominantly Sikh migrants that unsuccessfully challenged existing immigration policies restricting migration from Asia in 1914 — is an example of how the exhibition explores attitudes about race and religion.

Chinese Students Football Club, British Columbia Mainland Champions 1933, C.B. Wand, early 1930s. University of British Columbia Library, Rare Books and Special Collections, The Chung Collection, CC_PH_00051 Standing, left to right: William Lore (secretary), Gibb Yip, Jackson Louie, Jack Soon, Shupon Wong, Horne Yip, Charles Louie (manager), Gam Jung, George Lam (treasurer). Sitting, left to right: Lem On, Dock Yip, Art Yip, Quene Yip, Frank Wong, Buck S. Chung

Further, government policy toward Chinese immigration to Canada reflected racial attitudes of the time. The Chinese head tax, instituted after the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway, was systematically increased in the early 1900s. In 1923, the federal government went beyond the fee-based admission policy of the head tax and passed the Chinese Immigration Act, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act. It effectively cut off any further migration from China. The act remained in effect until 1947.

Chinese Canadians maintained community solidarity and fought for their rights through a variety of community associations throughout the interwar period. The Chinese Students Soccer team — based in Vancouver, British Columbia — was a tangible reminder of the Chinese community’s resilience in this difficult period. Founded in 1920 and winners of the prestigious Mainland Cup in 1933, the team transcended prejudices and racial boundaries of the time: Chinese and white people were at least equals on the field.

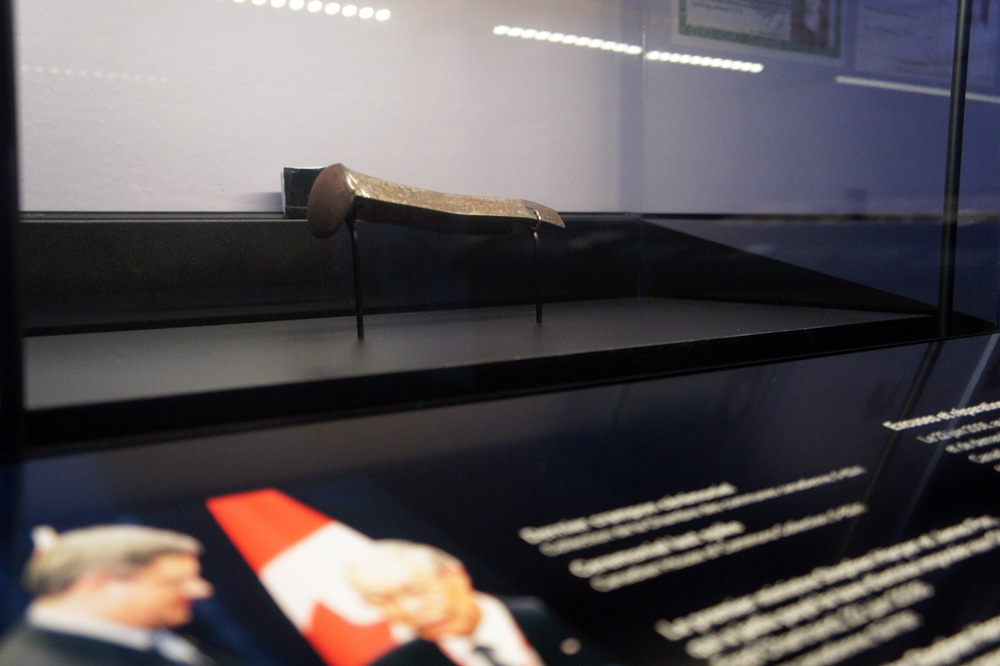

The legacy of such policies is also an important element within the exhibition. A ceremonial spike given by Chinese-Canadian leaders to Prime Minister Stephen Harper during the 2006 federal government apology for the head tax is a powerful symbol of the Chinese-Canadian community’s historical presence in and contributions to Canadian society.

The ceremonial spike given by Chinese-Canadian leaders to Prime Minister Stephen Harper on display in the Canadian History Hall. Canadian Museum of History

During the Second World War, a mix of racism and fears about domestic security led the Canadian government to use the War Measures Act to intern, relocate and revoke the voting privileges of thousands of Japanese Canadians. After the war, changing social attitudes and community-led efforts for equality led to a new, more inclusive citizenship and voting rights. Restrictive legislation on Chinese immigration, Japanese-Canadian relocation regulations and other discriminatory measures were lifted.

Throughout the postwar era, Canadians worked to broaden social and legal recognition of rights and identities, creating an increasingly open, accepting and diverse Canada. When Baltej Singh Dhillon applied to the RCMP in 1988, he was told he could not wear his turban — a fundamental part of his Sikh religion — with his uniform. He challenged the policy. A heated public debate ensued as many resisted changes to the RCMP uniform. In 1990, the federal government intervened and the RCMP changed its policy to accommodate the Sikh turban. The conflict and ultimate success of Baltej Singh Dhillon’s fight is represented in the third gallery by one of Singh’s RCMP uniforms, with his official-issue turban, along with examples of pins issued by organizations opposed to the change.

One of Baltej Singh Dhillon RCMP uniforms on display in the Canadian History Hall. Canadian Museum of History

The Canadian History Hall was designed to incorporate multiple perspectives and experiences to tell the stories of success, struggle, challenge, loss, achievement and hope that have shaped, and continue to shape, the ongoing history of Canada. These examples of Asian-Canadian stories featured in the Hall provide compelling illustrations of how this approach informed the exhibition.