Pandemic Protests and “Freedom Convoy” Context

This month marks the one-year anniversary of the end of the month-long protests known as the “Freedom Convoy.” It also marks the one-year anniversary of the invocation of the Emergencies Act by the federal government ― a historic first in Canada ― which was meant to help clear Canada’s capital of protesters (and their vehicles) occupying the downtown core, in addition to dealing with blockades of key border crossings and smaller protests across the country. In the coming days, the Public Order Emergency Commission (POEC) will release its report, including recommendations about possible changes to the Emergencies Act and how it should be used in the future.

Emotions about the Convoy remain high across the country, but particularly in the Ottawa-Gatineau region. Cleanup of the city in the aftermath of the protests was swift ― so swift that it made collecting any objects difficult. Nevertheless, the research team at the Canadian Museum of History has been working to document this important moment in Canada’s pandemic experience, as part of its broader efforts to document the COVID-19 pandemic.

Public Health Protests Past and Present

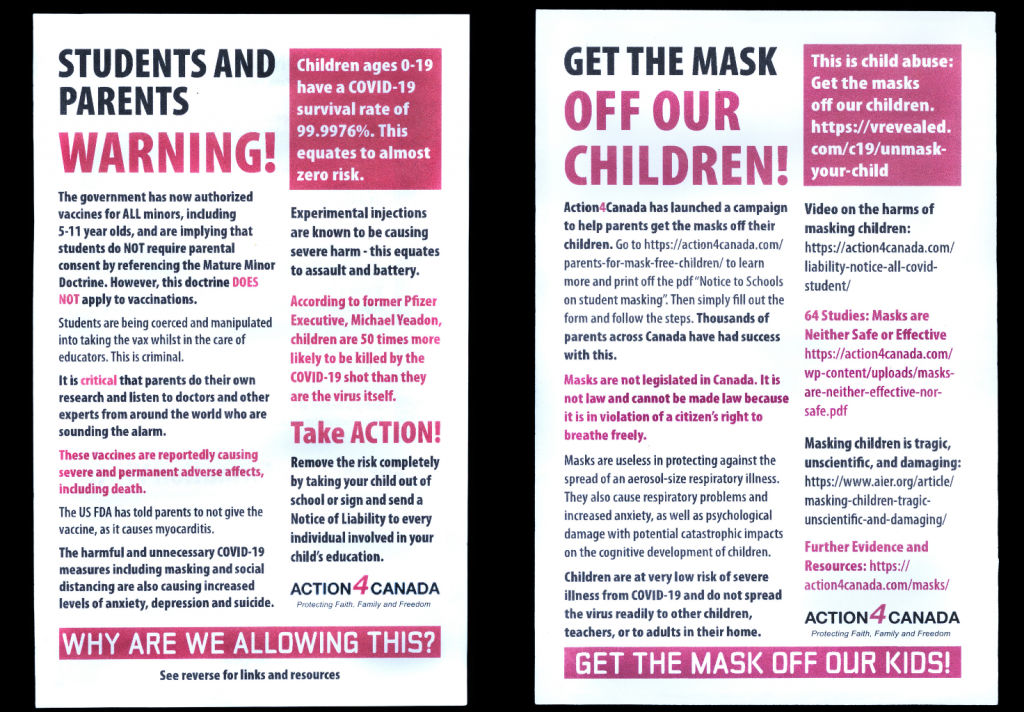

Action4Canada flyers handed to parents as they picked up their children from an Ajax, Ontario school in February 2022, 2022.50.1.

As the protests played out in Ottawa, similar rallies were organized across the country in support of the Convoy. Researchers have been able to recover anti-public health materials from these events. These flyers, for instance, were handed to an Ajax, Ontario mother in early February of 2022 as she picked up her child from school. Upon arriving home, she realized that the flyers called for an end to COVID-19 vaccine and mask mandates, while also making claims about the dangers of vaccines and other public health measures like masking and social distancing.

Describing itself as a grassroots movement founded on “Judeo-Christian biblical principles,” Action4Canada aims to unite Canadians in opposition to policies it sees as harmful to Canadian society. The group is known for its strong views on freedom of speech and its opposition to what it calls “political Islam,” “political LGBTQ,” and 5G technology. These flyers include numerous claims that contradict accepted scientific evidence and public health advice from the World Health Organization and Health Canada. Many of these conspiracy theories were, or are, self-propagating. Like anti-vaccine and anti-public health protest movements of the past, the actions of groups like Action4Canada showcase how fear and misinformation can flourish during public health emergencies.

Community Response: The “Battle of Billings Bridge”

1) “Battle of Billings Bridge” t-shirt given to Robert Talbot by a neighbour, 2022.39

2) Selfie taken by Talbot during his participation in the “Battle of Billings of Bridge,” February 13, 2022

It was also important to collect perspectives of Ottawa residents during the protests. A key flashpoint was the weekend of February 12–13 when, frustrated by a lack of action from police, some downtown residents organized actions of their own. The “Battle of Billings Bridge” was one of the highest profile community-led initiatives, organized via social media networks and intended to block further protesters from entering downtown.

Window signs made by the family of Robert Talbot, 2022.39

Robert Talbot decided to join the checkpoint at Billings Bridge in a show of solidarity and frustration. Talbot lives with his family in Ottawa’s Centretown neighbourhood. He, his partner, and their young children had all been subject to the noise, lewd signs, air pollution, dangerous driving, and, in the case of his 11-year-old son, harassment about wearing a mask while walking home from school. He and his family also decided to counter what they saw as the Convoy’s appropriation of the Canadian flag by putting handmade signs in their home’s front window that said, “It’s our flag too!” and “We (heart) Science!”

Review and/or Reform? Commissions of Inquiry

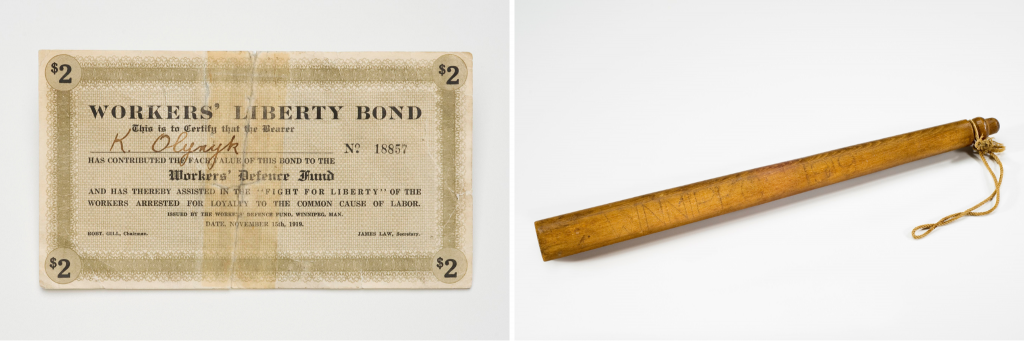

1) Canadians could pledge their support for striking workers through Workers’ Liberty Bonds, funded by donations to the Worker’s Defence Fund, run by the Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council and the One Big Union. Worker’s Liberty Bond, 1919. CMH M-555 a-b

2) Winnipeg Special Police billy club, Retained by J.S. Woodsworth, Protestant minister and social activist, 1919, Gift of Grace MacInnis, CMH, D-9261

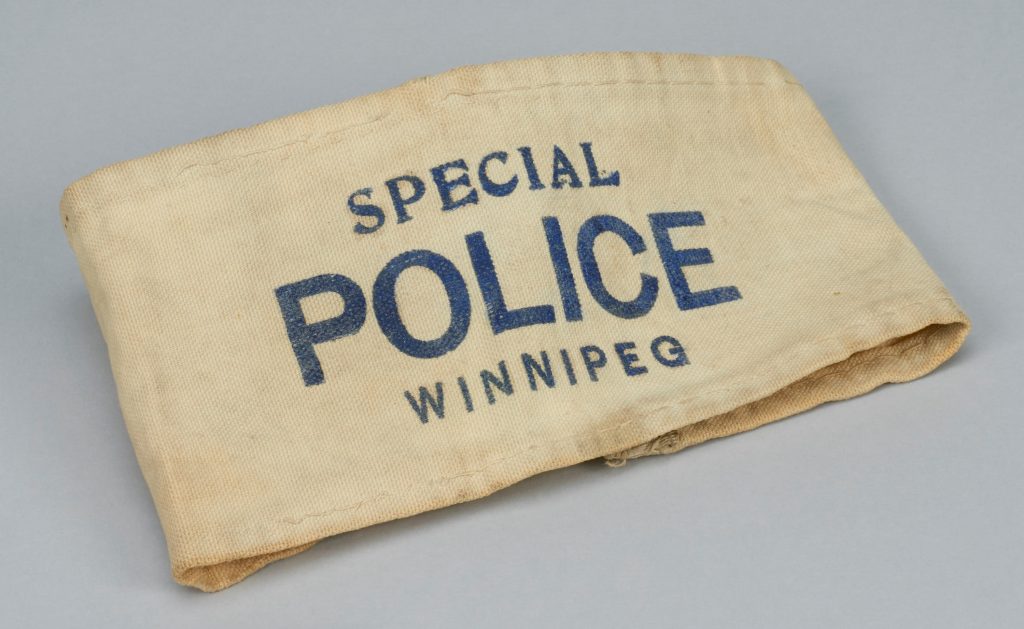

As for what kind of reforms or changes the POEC might recommend in its report, public security and police inquiries of the past provide some useful context. In May 1919, roughly 30,000 Winnipeg workers — angry about high inflation, dismal working conditions, and minimal labour rights (particularly collective bargaining rights) — joined a building-trades strike already in progress. The Winnipeg General Strike sparked large sympathy strikes across the country, and tensions in the city were high. Government and the business community reacted swiftly: 1,800 special constables replaced sacked municipal police officers. On June 21, 1919, the mounted police forcefully suppressed a final mass demonstration, which ended with two dead, 34 wounded, and 84 arrested.

Winnipeg Special Police arm band, 1919, Gift of the Winnipeg Police Museum, CMH, 2006.25.3

An oft-neglected facet of the end of the strike was a special Royal Commission negotiated between strikers and the Manitoba provincial government to investigate the factors leading to the strike and possible remedies. Led by respected provincial jurist Hugh Amos Robson, the commission’s report laid bare the growing class disparities in postwar Winnipeg, arguing, “There has been and there is now an increasing display of carefree, idle luxury and extravagance on the one hand, while on the other is intensified deprivation.” While many of its recommendations, particularly those connected to collective bargaining rights, went unheeded for decades, it remains a valuable perspective on economic conditions of the time.

The October Crisis and the Emergencies Act

A more recent example of investigation after a public emergency came in the aftermath of the October Crisis in Quebec in 1970. The invocation of the War Measures Act ― granting authorities sweeping search and detention powers ― marked its first use in peacetime.

1) Paperboy for the Ottawa Journal announcing invocation of the War Measures Act, October 16, 1970, Photo by Peter Bregg, Canadian Press, 9224239

2) Ballistic Protective Helmet, 1960s, Canadian War Museum, 19810910-003

In the aftermath of the crisis, both the Quebec provincial government and the federal government called commissions of inquiry investigating this suspension of civil liberties and the ethical implications of police actions during the October Crisis. The recommendations of the two provincial inquiries in Quebec focused mostly on preventing abuses of power by police in future crises, while the federal McDonald Commission was a wider-ranging investigation of RCMP behaviour during and after the October Crisis, including illegal raids of political party headquarters and media offices. The latter’s recommendations would take years to implement, but brought significant change through the severing of national security responsibilities from the RCMP to a new body, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service in 1984. A new federal Emergencies Act replaced the War Measures Act in 1988, another of the commission’s recommendations. The new Act provided a narrower scope of powers to be used in national emergencies (particularly surrounding police powers), while also providing broader parliamentary oversight to its use. The new law also required a full public review after each invocation of the powers of the Act.

Whether or not this inquiry will trigger substantive change and become another record for future historians remains to be seen, but these layers of perspectives will doubtless prove valuable in future explorations of Canada’s pandemic experience.

Further Reading

- Tom Mitchell, “Strike or Revolution? H.A. Robson’s Inquiry and the Winnipeg General Strike,” Manitoba Law Journal Vol. 42 (no. 2), 56-84.

- Reg Whitaker, Gregory S. Kealey, and Andrew Parnaby, Secret Service: Political Policing in Canada from the Fenians to Fortress America (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012).

James Trepanier and Daniel Neill

James Trepanier is the Canadian Museum of History’s Curator for Post-Confederation Canada. His research areas touch on the social, cultural and political history of Canada in the 20th century. Originally from British Columbia, James credits debates at the family dinner table with helping to spark his interest in history and education.

Daniel Neill is the Researcher in Sport and Leisure at the Canadian Museum of History. He is also a musician and Ph.D. candidate in ethnomusicology at Memorial University of Newfoundland.