On September 2, 2017, the Government of Canada redrew the boundary of the Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site of Canada to reflect the final resting places of both Franklin Expedition ships. This National Historic Site, discovered with the aid of carefully preserved Inuit oral histories, recognizes the historical importance of the wrecks, as well as their Inuit connection. While researchers from Parks Canada and the Government of Nunavut continue to investigate the sites, visitors to the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England, have since July 2017 been learning more in a new exhibition, Death in the Ice. The exhibition, developed by the Canadian Museum of History along with partners that include Parks Canada, the National Maritime Museum, the Government of Nunavut, and the Inuit Heritage Trust, opens at the Canadian Museum of History on March 2, 2018.

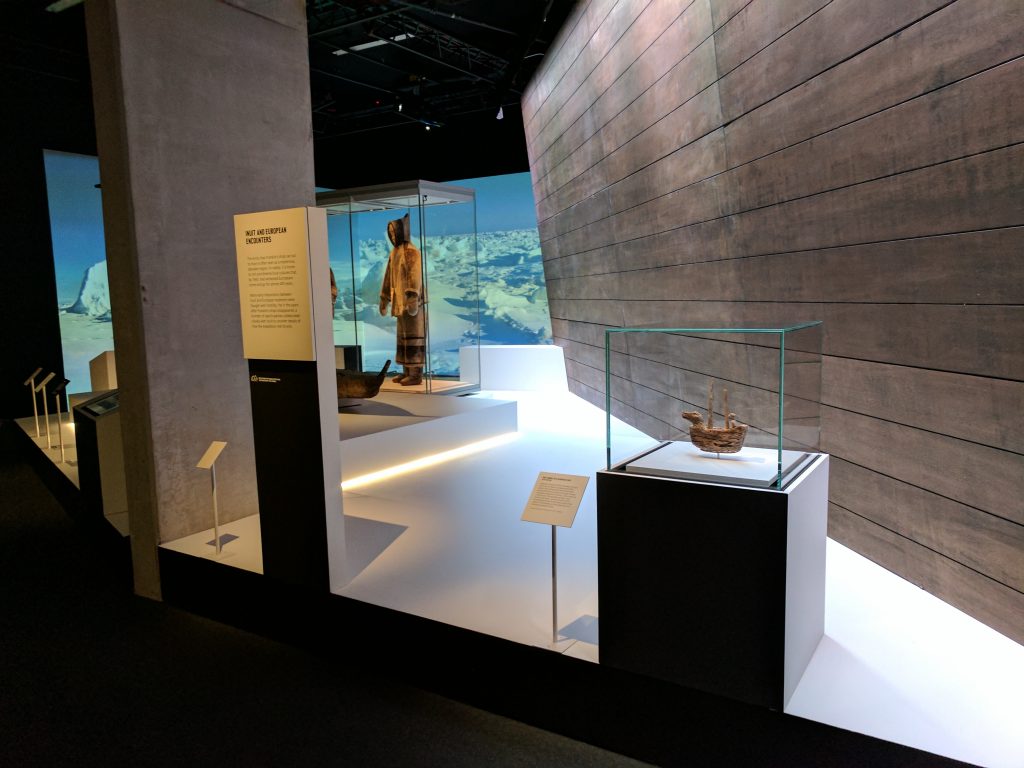

The introductory area of Death in the Ice at the National Maritime Museum includes an Inuit carving of a European ship (foreground).

Photo: Canadian Museum of History.

Early on, the exhibition team — Claire Champ (Creative Development Specialist), Danielle Goyer (Project Manager), Kerry McMaster (Scenographer/Designer), and Karen Ryan (Curator) — recognized that the story of Franklin’s 1845 expedition could only be told by acknowledging the role of Inuit experts in understanding what happened to the expedition. The reason for this is simple: Inuit were the last to see the ships and their crews. And those encounters, preserved in oral histories and shared with Parks Canada and its partners, contributed directly to the discovery of HMS Erebus and Terror.

A deliberate decision was thus made that some of the first artifacts encountered in the exhibition be Inuit. These include a full-sized kayak, male and female summer outfits, a small wooden carving of a 16th-century European ship, and a variety of tools made from local Arctic materials. Alongside these objects — all from the Canadian Museum of History — are similar examples from the National Maritime Museum. However, the latter Inuit artifacts differ in one important respect: they were made with wood and metal from the Franklin expedition.

Inuit summer outfits and a kayak, all more than 100 years old, at the National Maritime Museum. The listening station (bottom right) features Louie Kamookak speaking about the ongoing importance of the Inuit oral history tradition. Photo: Canadian Museum of History

The introductory area also includes ambient Inuktitut, the language spoken throughout most of Nunavut. This audio is based on an interview with Mark Tootiak, conducted by Dorothy Harley Eber in 1999, describing meetings between expedition crewmen and Inuit after Erebus and Terror were abandoned. This account, and another by Inookie Adamie in 1998, are featured in listening stations later in the exhibition, and are also included in Dorothy’s book Encounters on the Passage: Inuit Meet the Explorers. Her original Northwest Passage interviews, comprising 81 audiotapes, are now in the Canadian Museum of History Archives.

A showcase at the National Maritime Museum featuring Inuit objects made with locally available resources, alongside those using materials from the Franklin Expedition. Photo: Canadian Museum of History

In 2016, the Franklin exhibition team was also privileged to interview Louie Kamookak, an Inuit historian and expert on the Franklin expedition. Louie’s knowledge of oral histories — particularly those concerning the Northwest Passage — is unmatched, and his efforts to assemble this information have helped reveal what ultimately happened to the expedition. Louie also provided important cultural context about why the oral transmission of accurate and detailed knowledge remains a key part of Inuit life.

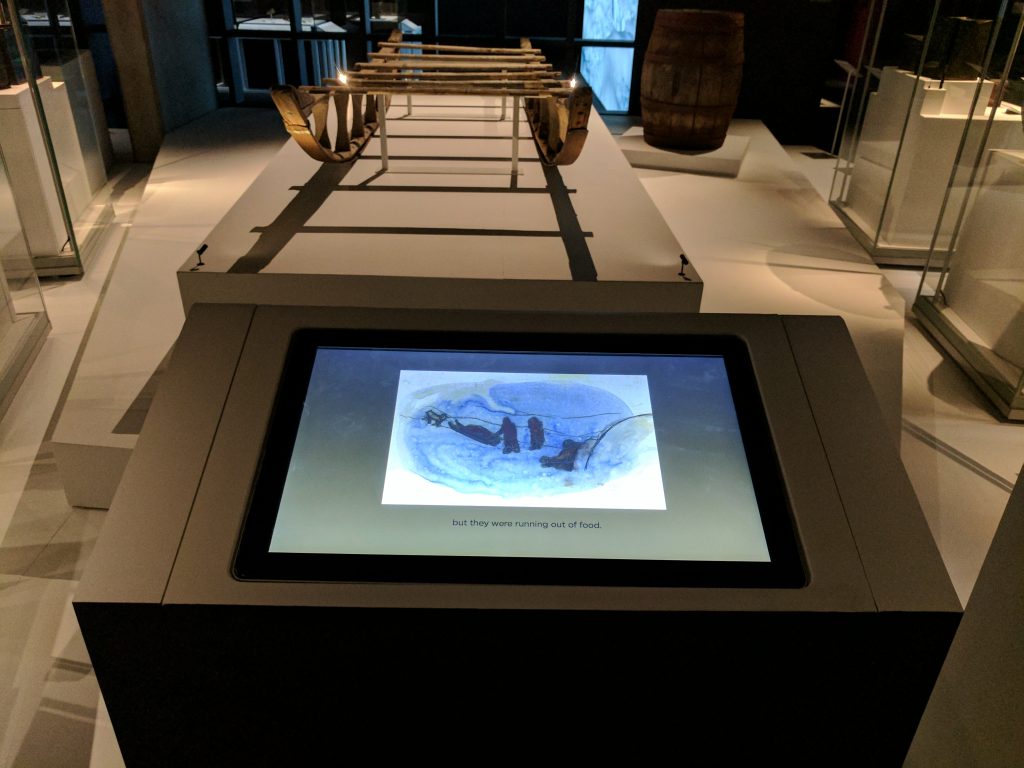

An oral history listening station, featuring Heather Campbell’s illustrations, at the National Maritime Museum. Photo: Canadian Museum of History

Exhibition visitors can listen to these testimonies in Inuktitut, French, or English at four listening stations. Each is illustrated with beautiful watercolours by Heather Campbell, an Inuit artist from Rigolet, in Nunatsiavut (Labrador). Heather’s images were inspired by details relayed at that particular station, and are meant to draw the eye and encourage visitors to learn, first-hand, from Inuit historians.

Death in the Ice is on view at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich until January 2018. It opens at the Canadian Museum of History on March 2, 2018. More information on the Wrecks of the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site of Canada is available via the Parks Canada website.