There are so many stories that came out of researching those left behind in the Barrack Hill Cemetery, it was difficult to narrow them down to the few discussed in this blog series. Almost all the individuals found at the site could be classified as working class, except for maybe one. It’s his life that I will introduce you to today, not because he’s more worthy than the others, but because he provides a contrast that helps to contextualize the life and times of this population.

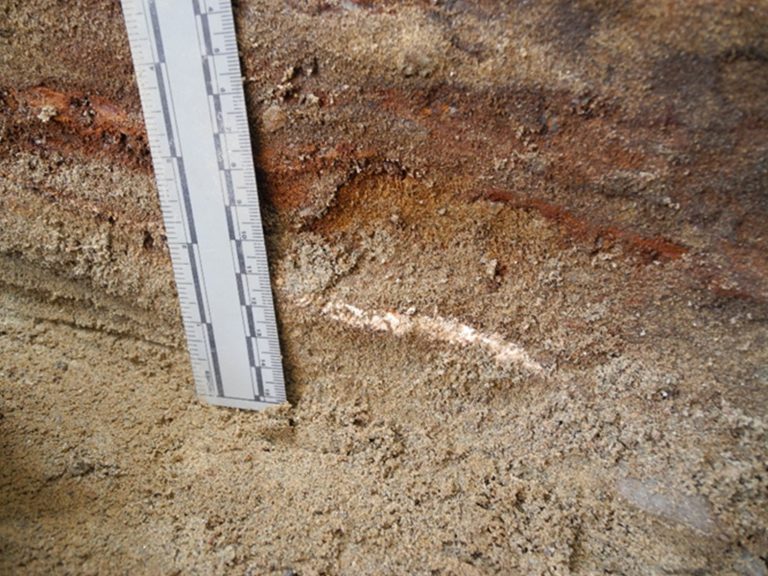

This man’s grave was identified by a patch of red sand that sat on his coffin lid. No others at the site had such a feature, inspiring us to refer to him as “Iron Man.” The red was a product of the rusting away of his coffin plate to the extent that no engraving could be discerned. Though the deterioration meant that we couldn’t read who he was, what he did, or when he lived and died, the presence of the coffin plate alone spoke to a level of wealth not present in the other graves from the site.

Close-up of a patch of red sand found on the coffin surface.

(Mortimer, 2014)

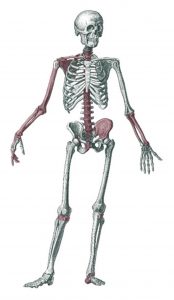

Illustration with the bones that remained in his grave marked in red.

After over a century of disturbance, very little actually remained of his skeleton, but there was enough for me to determine that this was a male. He was between 35 and 49 years old when he died, and he probably stood about 5’4” to 5’6” tall.

I noticed other features that suggest this individual led a life in contrast to the others buried at the site. He was able to survive a bout of tuberculosis that left scars on his ribs when others were not so fortunate. Was he in better health? Did he have access to a better diet and medical help?

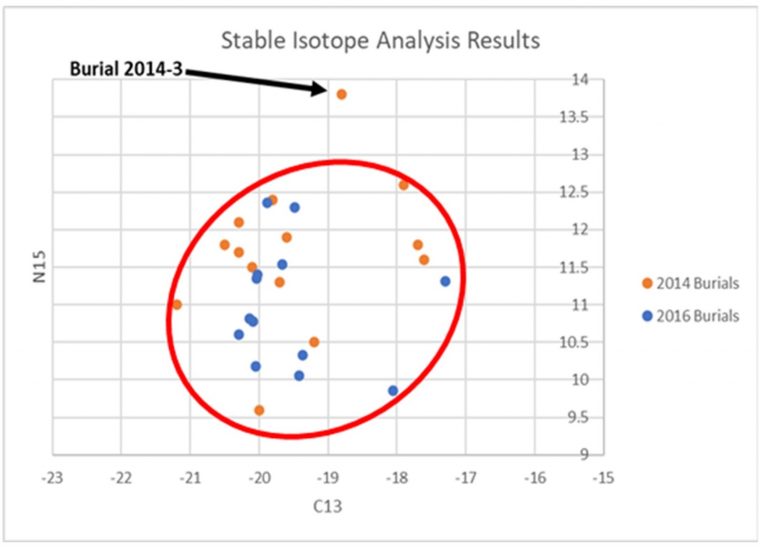

He also died with a condition called DISH (diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis), which has been linked to a rich diet. Stable isotope analysis confirmed this by indicating that he had a diet heavier in marine resources than his counterparts. All of this points to a person who was wealthier than the other residents of this cemetery.

Scatterplot showing the N15 results for this man as an outlier to the rest of the cemetery population.

(Young, 2023)

So, if he was wealthy, why was he left behind in this working class burial ground? The answer may lie in his possible cause of death: cholera.

Cholera in Bytown

The Barrack Hill Cemetery served two cholera outbreaks, one in 1832 and the other in 1834, which claimed many lives in the early years of Bytown. Since the cause of cholera was not understood at the time, it was often believed that it spread through “vapours.” This prompted the Bytown Board of Health to issue recommendations for the burial of cholera victims.

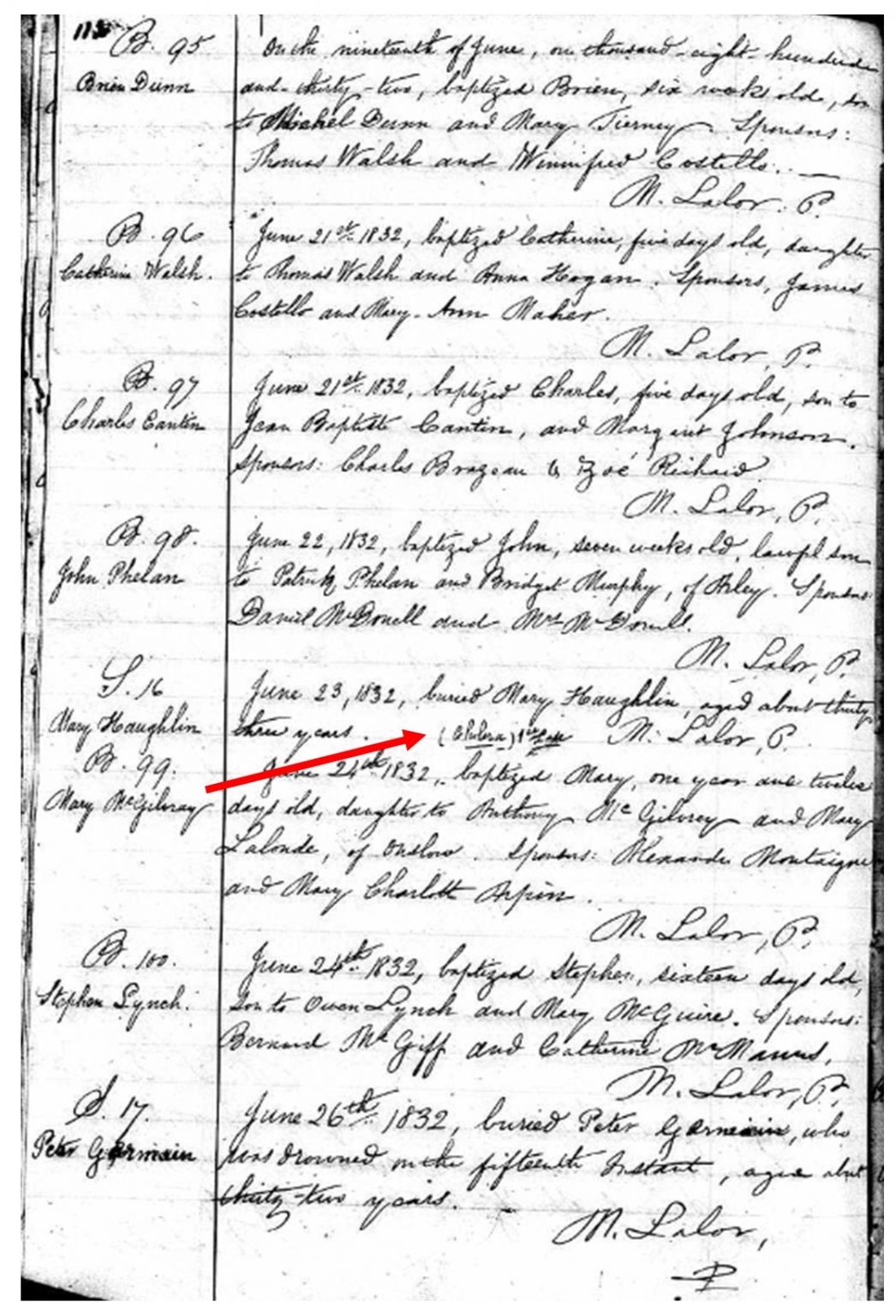

Catholic baptism, marriage and burial registry. The red arrow identifies the first cholera victim buried at the Barrack Hill Cemetery, on June 23, 1832. Between the end of June 1832 and the end of September 1832, 77 percent of those buried by the Catholic priest died of cholera.

(Ontario, Canada, Roman Catholic Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials, 1760–1923)

Board of Health recommendations

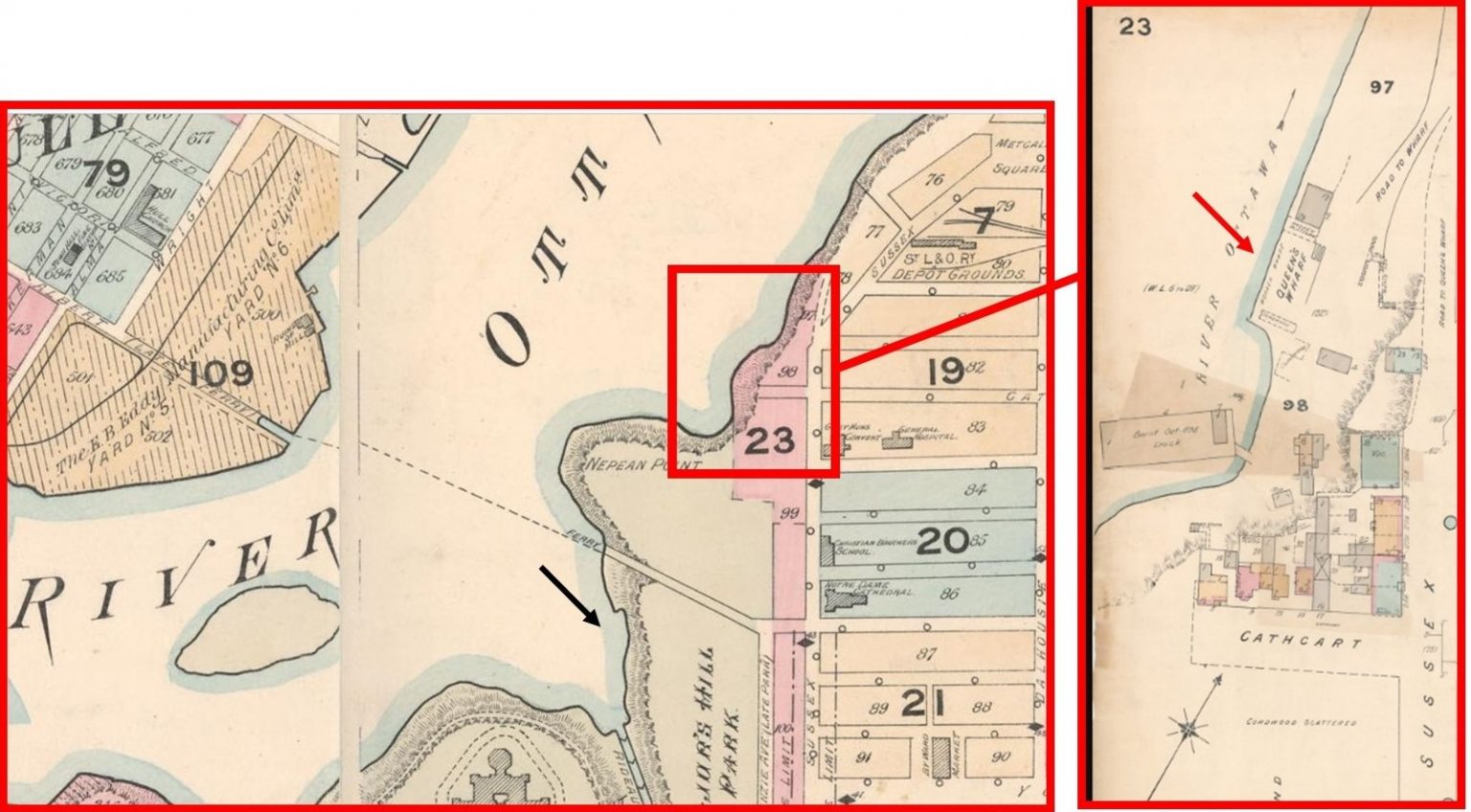

Ottawa insurance plan 1888-1901, with the position of the cholera wharf northeast of Nepean Point.

(Library and Archives Canada)

In 1832, a special wharf was built for the quarantining of steamer ships and the triaging of their passengers who may have fallen sick during their voyage (red arrow), in an effort to limit the spread of cholera in town. This wharf, called the Cholera Wharf and then Queen’s Wharf, was built on the northeast side of Nepean Point, around the promontory from the main wharf (black arrow). A temporary isolation hospital was set up just above, on the southeast side of present-day Sussex Drive, between where Cathcart and Bolton Streets end, to tend to those who were sick with cholera.

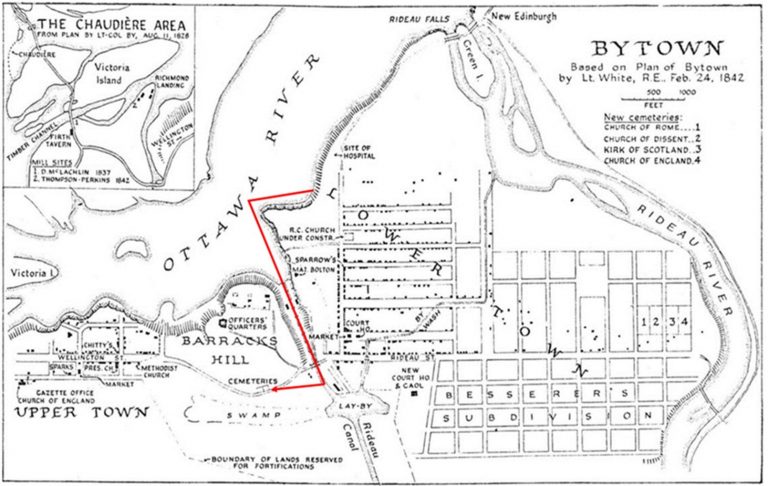

In addition to the establishment of these structures, the Bytown Board of Health also introduced strict rules pertaining to those who passed away from cholera. This included stipulations that cholera victims had to be buried within three hours of death, their coffins had to be filled with slacked lime (calcite), and had to be covered by at least four feet of earth. Mourners were discouraged from carrying the corpses along the main streets and instead instructed to take a water route to the Barrack Hill Cemetery (Brault, 1946, 235).

The burial ground’s location on an isolated stretch of road close to the waterway made this a viable option. Records indicate that Simon Fraser, the sheriff, asked that funerals be conducted wholly by the river and the canal to the cemetery west of the canal basin, rather than by road through the town, and that persons falling ill in Bytown be brought to the hospital by the same route.” (Bond, 1964, p.30)

A map displaying the likely water route from the area of the Cholera Wharf and hospital to the Barrack Hill Cemetery.

(Haydon 1909)

Cholera and Iron Man

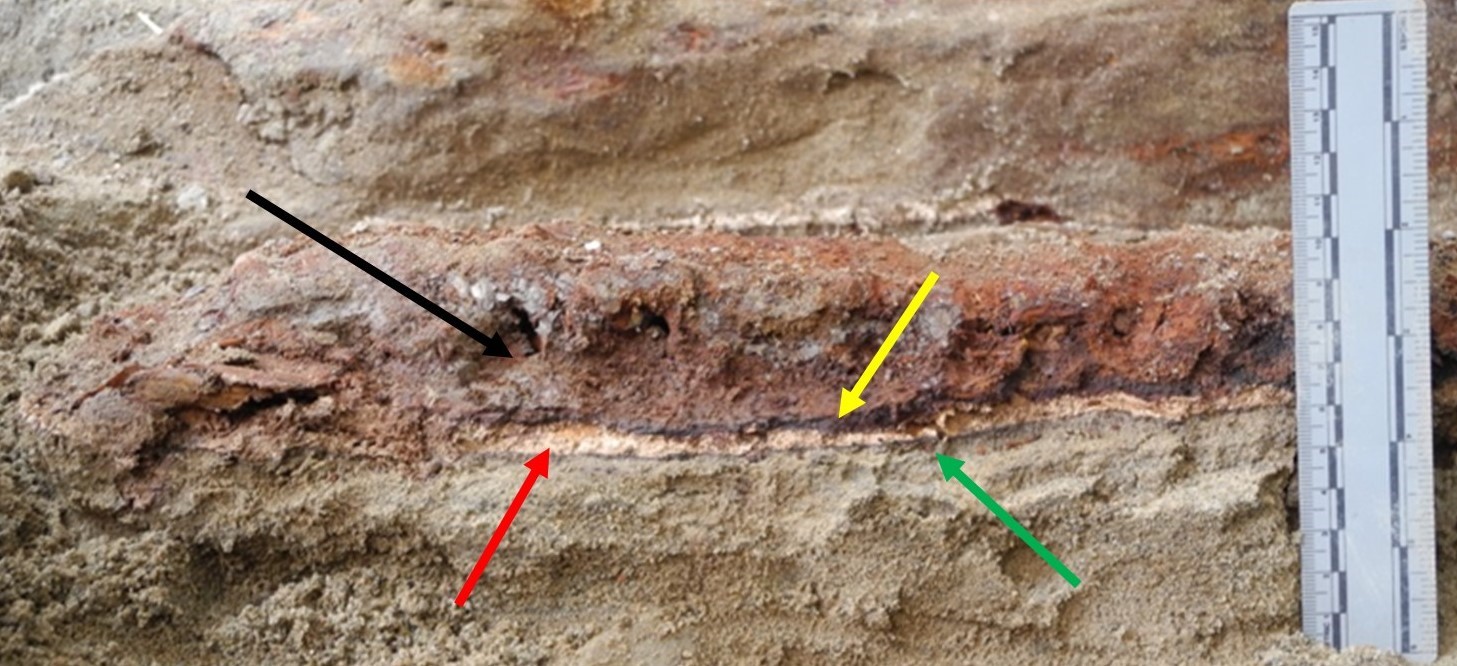

Compressed stratified cross-section of burial showing oxidized coffin plate (black arrow), coffin lid wood (yellow arrow), calcite (red arrow), and coffin floor wood (green arrow). The skeletal remains were found beneath the coffin lid layer.

(Young, 2017)

While excavating Iron Man, we found a white substance between his skeleton and the coffin floor. In the field, this substance appeared greasy, so we originally believed it was adipocere (preserved fat tissue). However, the excavations took place during a very wet spring and once allowed to dry in the lab, the substance became chalky. I sent samples to Parks Canada for analysis, and they determined that it was calcite and, most likely, quick lime.

Had this wealthy man succumbed to cholera? Could this explain why his remains were not relocated to Sandy Hill Cemetery, for fear of spread of the disease? It’s an interesting supposition, but in the end we’ll never really know. For the purposes of my investigation into the lives of those left behind, I’m happy that he was buried there, as he serves as a contrast to those who could not afford medical care or a good and varied diet, or even an elaborate coffin. In the end, they all were laid to rest in the same earth, equal in death.

Find out more

Read more about the findings in the Barrack Hill Cemetery in the blog series, Bone Detective: Mysteries of Those Found Beneath Downtown Ottawa.

Janet Young

Janet Young specializes in the study of human skeletal remains, and has been working at the Canadian Museum of History since 1994.

Read full bio of Janet Young