A very special piece of paper

Of the many treasures brought together for the exhibition Death in the Ice – The Mystery of the Franklin Expedition, one of the most exciting artifacts is the Victory Point Note. Though written on a single piece of paper, the document speaks volumes about the fate of Sir John Franklin and his crew.

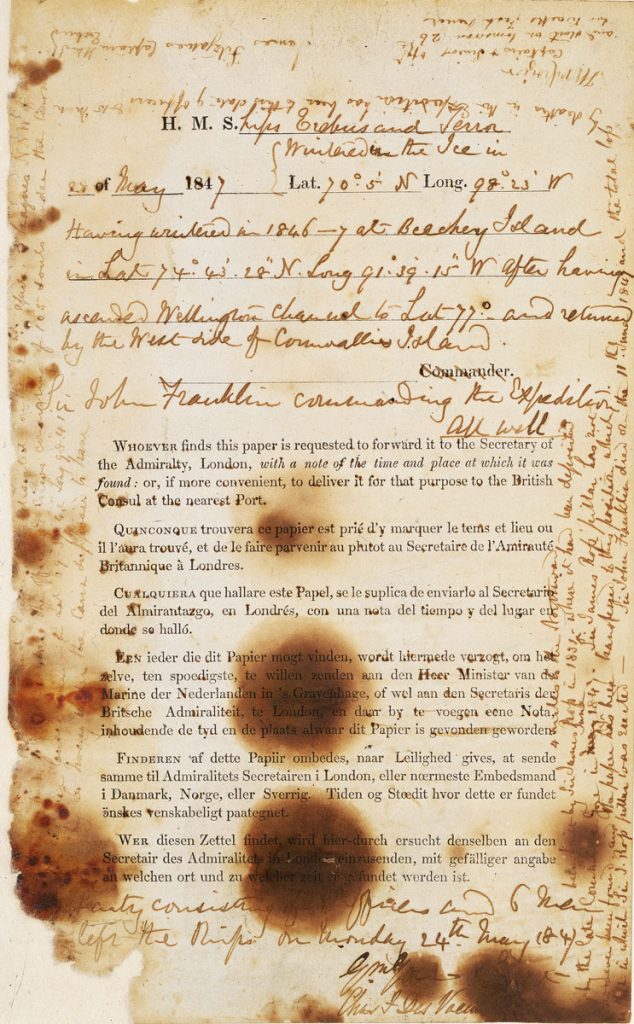

The note is actually a standard preprinted Admiralty form with two handwritten messages. The first, written in May 1847, confirmed that Franklin was in command of the Expedition and that all was well. The second message, added in April 1848, tells a much different story. Twenty-four people, including Franklin, were dead. Even more alarmingly, the Expedition ships, HMS Erebus and Terror, had been deserted after being trapped by sea ice for 19 months.

The exhibition’s curator, Dr. Karen Ryan, explains that the Victory Point Note was found in 1859, just south of Victory Point on the northwest coast of King William Island, where Franklin’s surviving crew members came ashore after leaving their ships. It remains the only known record detailing the crew’s plan to walk to the Back River in a last attempt to survive. It is a crucial piece of evidence, and Ryan knew it would be an exciting addition to Death in the Ice.

Victory Point Note. © National Maritime Museum, London.

However, the note had never been displayed outside England before. Ryan admits she did not have high hopes of being allowed to display it in Death in the Ice. “But one thing I’ve learned,” she said, “is that it never hurts to ask.” Figuring the worst case scenario would be a “no,” she asked the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London, if it would allow the document to be included in the exhibition. To her delight (and surprise), the National Maritime Museum agreed — on the condition that the note would be very well protected.

“It was a big decision to let this significant piece of evidence travel and be put on display at the Canadian Museum of History,” said Amanda Gould, paper conservator at the Museum. Although the note was taken out of the Arctic in 1859, 11 years after it was left on King William Island by Franklin’s surviving crew, it likely suffered a lot in that time, getting wet and going through a number of freeze-thaw cycles. Since it was kept in a metal canister while there, it has rust stains, which can be very detrimental to the cellulose of the paper. “Understandably, the lender was concerned about the welfare of this very fragile document,” Gould said.

So how, exactly, do you safely display a 170-year-old piece of paper? “It was a pretty big challenge,” admitted Gould. The lender asked that the note be put into a case similar to the one Library and Archives Canada and the Canadian Conservation Institute produced for the display of two copies of the Proclamation of the Constitution Act. The multi-functional case was designed to protect documents with light-sensitive ink, both in storage and in travel. “Greenwich asked if our Museum could produce a case of that sort for the note’s travel and display, so that’s what we did.”

Gould makes it sound simple, but the process was extensive, involving a lot of back and forth between the museums. Following the lengthy process of gathering requirements, the Museum of History hired Zone Display Cases to finalize the design and fabricate the case.

Of the case’s many details, including its airtightness, the one that visitors will notice first is the SmartGlassTM. Designed to minimize the note’s exposure to light, this glass is opaque when no one is looking at the document. When a visitor pushes a button, an electrical voltage is applied, causing the glass to shift from dark to clear so he or she can see through it. As Gould explains, it is the high-tech version of protecting a painting behind a curtain until you want to look at it, at which point you pull the curtain aside.

The Museum always takes great care with its artifacts, but with a borrowed, weathered 170-year-old piece of paper — one that also happens to be a key clue in the Franklin mystery — it took even more precautions than usual. “We really upped the ante in terms of the methods and materials we used to display it,” said Gould.

This single piece of paper is a key piece of evidence in unravelling the Franklin mystery. Today, thanks to the efforts of Museum staff — and the trust that the National Maritime Museum placed in them — it plays a crucial role in the Museum’s groundbreaking presentation of that story.

The exhibition Death in the Ice – The Mystery of the Franklin Expedition is presented until September 30, 2018 at the Canadian Museum of History.

[Transcript of the Victory Point Note]

28 of May 1847

H.M.S.hips Erebus and Terror Wintered in the Ice in Lat. 70°5’N Long. 98°23’W Having wintered in 1846-7 [sic] at Beechey Island in Lat 74°43’28’’N Long 91°39’15’’W

After having ascended Wellington Channel to Lat 77° and returned by the West side of Cornwallis Island.

Sir John Franklin commanding the Expedition.

All well

Party consisting of 2 Officers and 6 Men left the ships on Monday 24th May 1847.

[signed] Gm. Gore, Lieut.

[signed] Chas. F. DesVoeux, Mate

25th April 1848

HMShips Terror and Erebus were deserted on the 22nd April 5 leagues NNW of this having been beset since 12th Sept 1846.

The officers and crews consisting of 105 souls under the command of Captain F. R. M. Crozier landed here — in Lat. 69°37’42’’ Long. 98°41’

This paper was found by Lt. Irving under the cairn supposed to have been built by Sir James Ross in 1831 — 4 miles to the Northward — where it had been deposited by the late Commander Gore in May June 1847.

Sir James Ross’ pillar has not however been found and the paper has been transferred to this position which is that in which Sir J. Ross’ pillar was erected.

Sir John Franklin died on the 11th of June 1847 and the total loss by deaths in the Expedition has been to this date 9 officers and 15 men.

[signed] F. R. M. Crozier Captain & Senior Offr

And start on tomorrow 26th for Backs Fish River

[signed] James Fitzjames Captain HMS Erebus