The Complicated Case of Juliette Gaultier de la Vérendrye

Note: Some of the archival documents cited in this post use historical terminology that is no longer considered appropriate.

Juliette Gaultier de la Vérendrye (1888–1972) is not a figure with whom I was well-acquainted upon my arrival at the Museum three years ago, and in all honesty I am not sure that I “know” her any better today. Still, Gaultier has proven to be a presence both enigmatic and fortuitous during the intervening years. The more that I learn about her, the more interesting the implications for the work that we do here become: What does it mean to care for and cultivate national museum collections and archives? What makes an object or a sound “Canadian”? And what might we learn from historical examples of cultural exchanges and encounters?

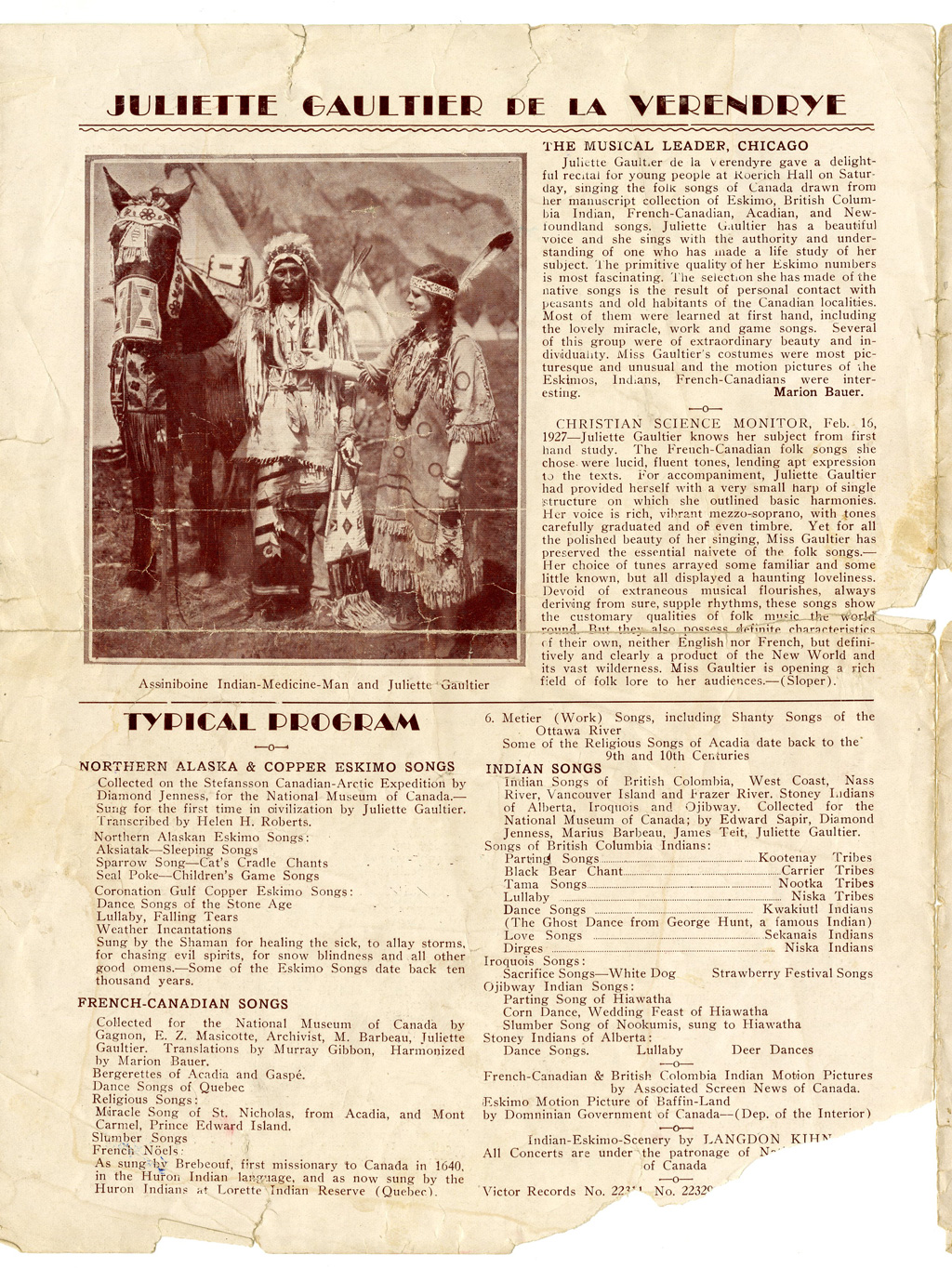

Juliette Gaultier de la Vérendrye promotional material. © Canadian Museum of History, Juliette Gaultier fonds, F218_2_001.jpg; Gaultier F218_2_002.jpg

Canadian soprano Juliette Gaultier was, and remains, a complicated character. Trained in Europe and then based in New York during the late 1920s, she performed what she called “Canadian folk songs” on the concert stage, seeking to entertain and educate her audiences.

Gaultier’s Town Hall debut in 1927 was a huge success[1], and she was later invited to perform a 16-week engagement at the Neighborhood Playhouse — a New York venue that celebrated avant-garde performance and experimentation. Gaultier’s connections in Canada and the United States during this period were significant and included figures like American portrait artist Langdon Kihn, Group of Seven painter Arthur Lismer, composer Marion Bauer, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King and National Museum of Canada anthropologists Marius Barbeau and Diamond Jenness.

These latter connections enabled Gaultier to access the archives of the National Museum (now the Canadian Museum of History), from which she drew First Nations, Inuit, French Canadian and Acadian song repertoires for her performances. She was also able to borrow clothing from the Museum’s collections for this purpose. Gaultier’s association with the Museum gave her performances an air of authenticity in the eyes and ears of her audience.[2]

- Langdon Kihn drawing of Juliette Gaultier de la Vérendrye, 1927. Gaultier is wearing a late 19th-century coat collected by George Comer from Qingailitaq on the west coast of Hudson Bay, ca. 1902. The coat was later sold to Franz Boas at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) where the original remains (983.011.001a). A letter from Gaultier to Barbeau confirms that she sat for the portrait in 1927: “Kihn is making my portrait in Eskimo attire…” © Canadian Museum of History, Langdon Kihn drawing of Juliette Gaultier de la Vérendrye, no 2013.65.1, photo Steven Darby, IMG2015-0023-0001-Dm.jpg.

- Photograph of Juliette Gaultier de la Vérendrye at the spinning wheel in costume, used to advertise the Canadian Folk and Handicrafts Festival in Québec City, Québec, 1928. Photo provided courtesy of CP.

- Juliette Gaultier de la Vérendrye wearing an Inuit parka, during the Canadian Folk Song and Handicrafts Festival at the Château Frontenac in Québec City, Québec, 1928.

- Juliette Gaultier de la Vérendrye at the Town Hall theatre in New York City, 1927. She is wearing a cedar bark cape that is on loan from the American Museum of Natural History. Stage setting by Langdon Kihn. The original photograph was taken by Associated Screen News for the Canadian Pacific Railway. © Canadian Museum of History, Juliette Gaultier de la Vérendrye fonds, (I-A-160M), B327, f.1., image no. 97-608.

It is difficult to know what to think of these images of Gaultier. Viewed through a contemporary lens, questions of representation and cultural appropriation are impossible to ignore. What does it mean for a singer to use museum collections in order to “authenticate” the presentation of expressive culture on stage? Related issues have been examined by scholars like Jessup (2008) and Slominska (2009), and take on tactile meaning within the museum context. While Gaultier’s work from this period is charted through photos, letters and other media, we have no equivalent information about how the cultural communities from which her repertoire was borrowed might have responded. What does Gaultier’s example tell us, quite literally, about historical voice and silence?

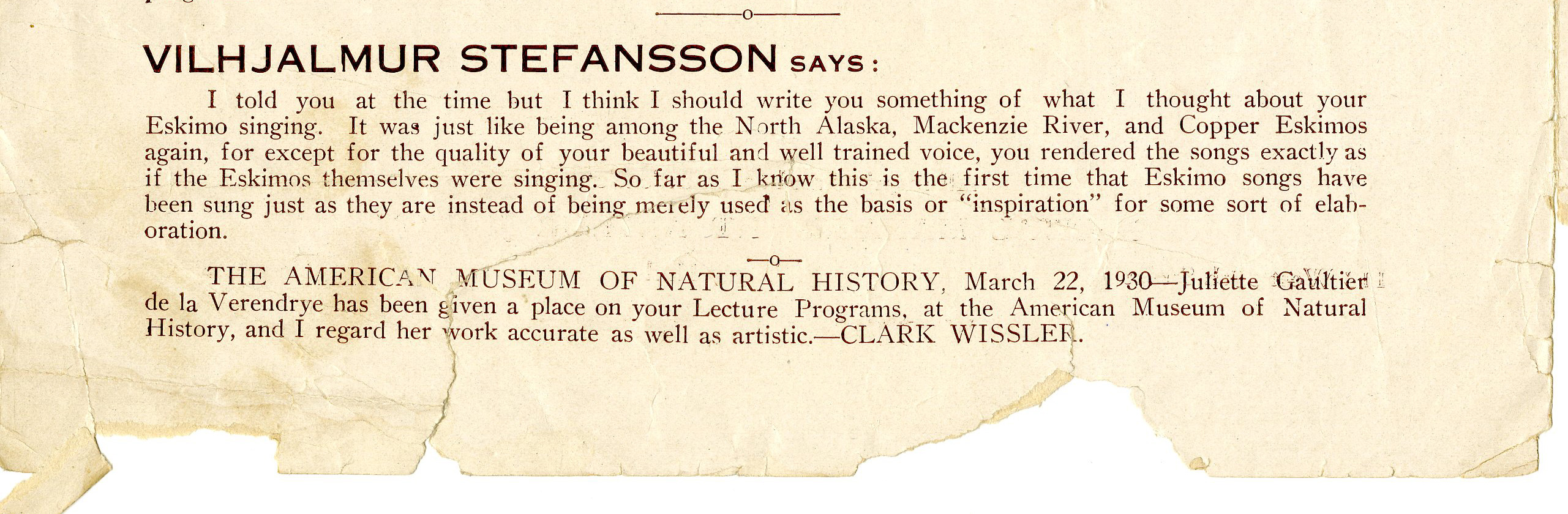

At the same time, Gaultier’s letters and interviews seem to suggest good — if naïve — intentions. In a 1930 interview, she asserts that her greatest interest is to hear First Nations and Inuit music sung, “either by the natives themselves, or at least when sung by white people they should be preserved in their natural form and the songs sung or harmonized to native instruments only” (The Phonograph Monthly Review, 366). Gaultier studied diligently to ensure the “accuracy” of her performances, and in a letter to Diamond Jenness, Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson writes, “So far as I know this is the first time that Eskimo songs have been sung just as they are instead of being merely used as the basis or ‘inspiration’ for some sort of elaboration.”

Gaultier did not become wealthy from her performances of “Canadian folk songs” and her success was not long lasting. Still, the questions raised by performances like hers continue to resonate, and underscore the complexity of cross-cultural exchange, representation and good intentions.

Further Reading

Canadian Museum of History archives. Marius Barbeau fonds.

Canadian Museum of History archives. Juliette Gaultier fonds.

Canadian Museum of History archives. Diamond Jenness fonds.

Canadian Museum of History archives. Noeline Martin fonds.

“Folk Song and Phonograph: Juliette Gaultier de la Verendrye reveals the treasure store of Canadian Folk Music.” The Phonograph Monthly Review (August 1930): 365-366.

Jessup, Lynda. “Marius Barbeau and Early Ethnographic Cinema.” In Around and About Marius Barbeau: Modelling Twentieth-Century Culture, edited by Lynda Jessup, Andrew Nurse, and Gordon E. Smith, 269-304. Gatineau, Quebec: Canadian Museum of Civilization, 2008.

Jessup, Lynda. “Tin cans and machinery: Saving the Sagas and other stuff.” Visual Anthropology, Published in cooperation with the Commission on Visual Anthropology 12, no. 1 (1999): 49-86.

Slominska, Anita. Interpreting Success and Failure: The Eclectic Careers of Eva and Juliette Gauthier. Doctoral dissertation, McGill University, 2009.

Footnotes

1. See Jessup (2008) and Slominska (2009) for further reading.

2. See Slominska (2009) for a detailed description of the event and its preparations (Chapter 2, pp. 10-15).