A century of time

Time is something we never seem to have enough of. We live through time. Each and every stage of our lives is marked by it. It creeps into our daily routines, bringing reminders of the turn of the seasons. We live through it, but are also aware of it as a more impersonal gauge of the days, months and years.

We remind our children that in the old days, such as the 1960s or the 1990s, things were done differently. Time as decade, or century, is an abstraction which our progeny can more or less comprehend; so we keep reminding them. The generation that walks city streets and sidewalks today, noses pressed to cellphones, can easily find the time by looking at their devices.

And yet there is nothing new here. This fixation with handheld devices has been with us for at least a century or more. Men and women have for years been turning their arms to glance at their watches to check the time. Before that, they might have reached for a pocket watch: tucked into the vest for a man; fixed to a chain worn around the neck for a woman.

There is one timepiece in the Museum’s collection that tells an interesting story about how time has evolved. It is a watch worn by a passenger or member of the crew aboard the Empress of Ireland, on the night the ship went down in the Lower St. Lawrence: May 29, 1914.

There is no doubt that many other watches were worn by people on the Empress. But this one is intriguing, because it offers so few clues about its past history. You can’t see the time: the dial face is no more. You can try to peek inside at some of the gears and levers through an aperture, but you really can’t see much.

We have not (yet) taken the watch apart, as the Smithsonian did in 2009 with Abraham Lincoln’s watch. Were we to do so, we would find the miniscule gears and inner workings that make it run. These are partially visible in the micrograph and x-ray images that we did take in our effort to better understand the material aspects of the watch. But the x-ray images showed nothing that was particularly conclusive: the thicker and denser metal parts appeared lighter; the thin metal parts appeared darker.

On the exterior, under the cover, certain markings visible to the naked eye, and machine-etched into the metal, allow us to identify the maker: Robert Ingersoll Bros, New York. Accompanying this are two series of patent-date strings, arranged in concentric circles. The outer and more recent circle provides these dates: June 29 (19)09, May 24, (19)10, Nov 12 (19)12; the inner rings stretch from January 1901 to June 1907.

The most recent of the dates, November 1912, suggests that the watch had been in the possession of its owner less than 2 years prior to the sinking of the Empress. The movement serial number, also etched into the metal, is 3212177, which — according to one online table of Ingersoll Watch Company serial numbers — suggests that the Empress watch may have been manufactured in 1911, although the patent dates suggest otherwise.

More revealing of the watch’s history is the interior label which, after conservation treatment, proved the identity of the item as a Yankee Dollar watch. However, this wasn’t immediately apparent. Instead, it was discovered once the paper conservator started piecing the fragmented label back together.

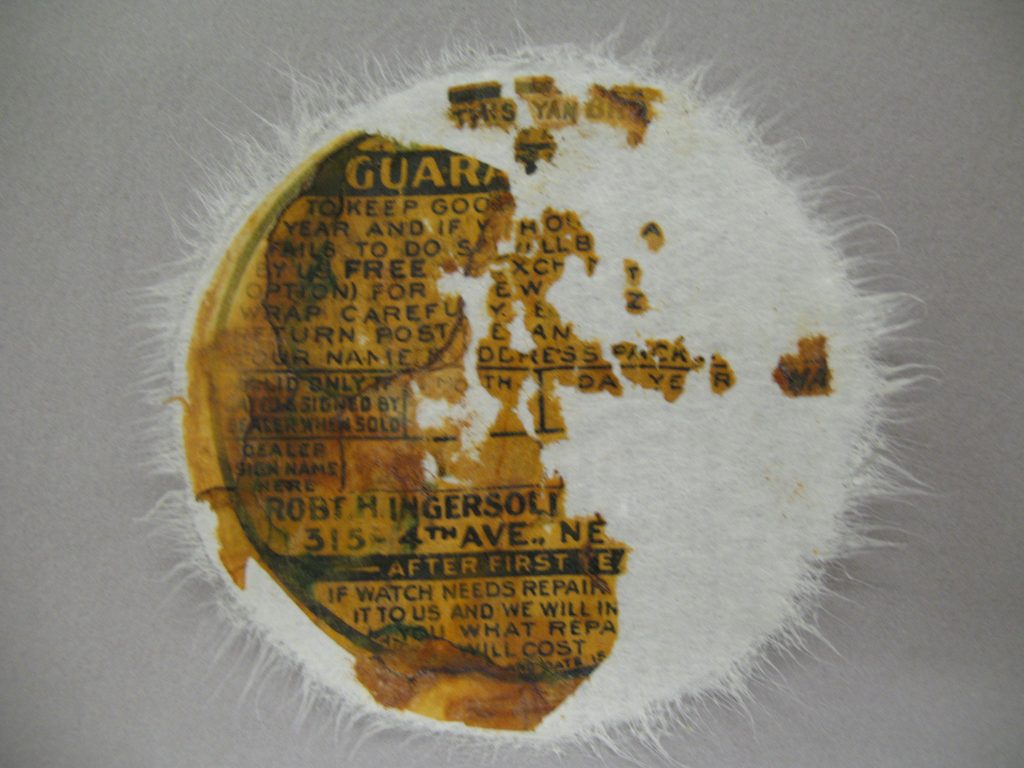

The largest label fragment is shown on the left side of picture, before treatment. This fragment was originally set inside the lid, which covers the reverse side of the watch.

Prior to treatment, the label consisted of one larger fragment, found loose within the lid of the watch, along with numerous smaller fragments — including one reading “THIS” that had remained adhered to the interior of the lid. The size of the largest fragment suggested that approximately half of the label was missing, its original size having corresponded to the interior dimensions of the lid. The largest fragment had many small tears and folds, and the paper surface was so abraded in some areas that it looked like a mat of fibres.

Most of the smaller fragments were found inside the mechanism cavity of the watch. The label is likely made of wove paper; however, the original colour, thickness and texture of the paper remain difficult to determine, as more than 90 percent of the paper’s surface is orange in colour, due to staining associated with corrosion of the watch components. Although not made primarily of iron, the watch contains iron screws and rivets.

Before treatment, the largest label fragment read:

GUAR_/TO KEEP GOO_/YEAR AND IF_/___TO DO_S/BY US FREE_/OPTION FOR_/WRAP CAREFU_/RETURN POST_/YOUR NAME_/LID ONLY/______SIGNED BY/DEALER WHEN SOLD/DEALER SIGN NAME HERE [________]/ROBTH_/315_AVE., NE/AFTER FIRST YE_/IF WATCH NEEDS REPAIR_/IT TO US AND WE WILL I_/YOU WHAT REPA_/WILL COST/ WAT______AND DATE IS/

During treatment, certain key fragments were found — one on line 1, which adds the following to the label text:

THIS/ YAN /GUAR_/TO KEEP GOO_/YEAR AND IF_/___TO DO_S/BY US FREE_/OPTION

During treatment, all of the recovered fragments, most of which were retrieved from the cavity of the watch, were adhered, one by one, to Japanese paper (white in this image). Japanese paper is frequently used for this kind of work, because it is strong but will not damage fragile paper fragments.

The “YAN” identifies this as a Yankee Dollar watch. Our work also made the inscription on line 3 more visible, where it refers to Robert Ingersoll and Brothers, the watch manufacturer:

WHEN SOLD/DEALER SIGN NAME HERE [________]/ROBT.H.INGERSOLL/BRO/MA/315_AVE.,

After treatment the paper, mounted on Japanese tissue, was placed onto a layer of polyester film, then reinserted into the inside of the watch lid.

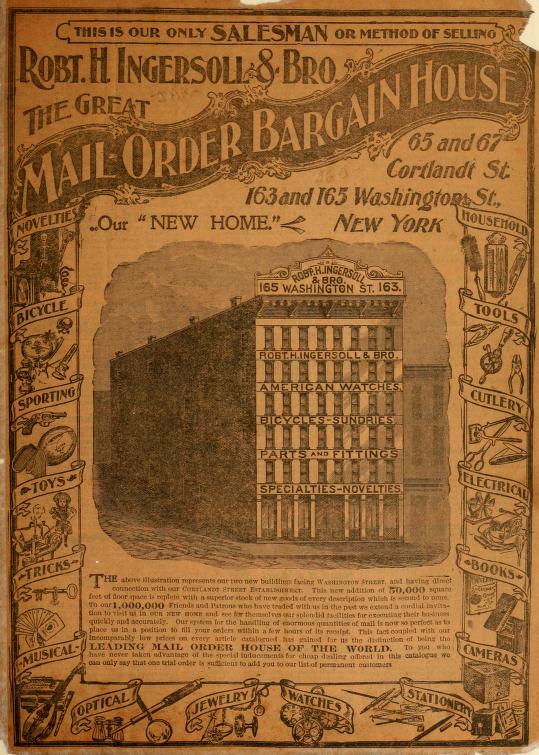

A gifted salesman-cum-entrepreneur, Robert Ingersoll began selling inexpensive pocket watches at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Within a couple of years, he was selling hundreds of thousands of Yankee Dollar watches made for him by the Waterbury Clock Company, a firm based in central Connecticut — a city with a significant population of French Canadians. Dollar watches were sold in Europe and elsewhere in North America, including Canada. By 1903, the company had an office in Montréal, Canada’s largest city.

Although, owing to the success of the company, there are many examples of Ingersoll “dollar” watches and watch labels in existence, only one in the Canadian Museum of History’s collection is associated with the wreck of the Empress of Ireland. There were other watches found on victims of the disaster; newspapers reports mention at least four. However, given the widespread nature of watch ownership at the turn of the century, this is probably a gross underestimate of the total number aboard.

A page from the Ingersoll Brothers catalogue, advertising the Yankee Dollar watch. The image shows a label on which Ingersoll’s iron-clad guarantee appears. Ingersoll was deliberately aiming at the mass-market. The advertisement reads thus: “We style ourselves ‘watchmakers to the American people’ because we make watches of guaranteed quality which the MASSES can afford to buy.”

Interestingly, most of the watches mentioned in the press at the time stopped somewhere between 2:15 and 2:19 a.m. on May 29, 1914. It is a reminder of how, in a time of disaster, time — the dimension through which we go forward in our lives — can suddenly, tragically, come to an end. The watch stops ticking; the collective human heart skips a beat.