Inuit Prints – Japanese Inspiration

This is the story of how Japanese printmaking techniques made their way to the Cape Dorset print studio in the Canadian arctic. In this excerpt from the Inuit Prints – Japanese Inspiration exhibition catalogue, written Dr. Norman Vorano, former Curator of Contemporary Inuit Art at the Canadian Museum of History, you can learn more about the introduction of Japanese printmaking traditions to the Cape Dorset studio by Canadian artist James Houston, and the inspired adaptation and innovation that ensued.

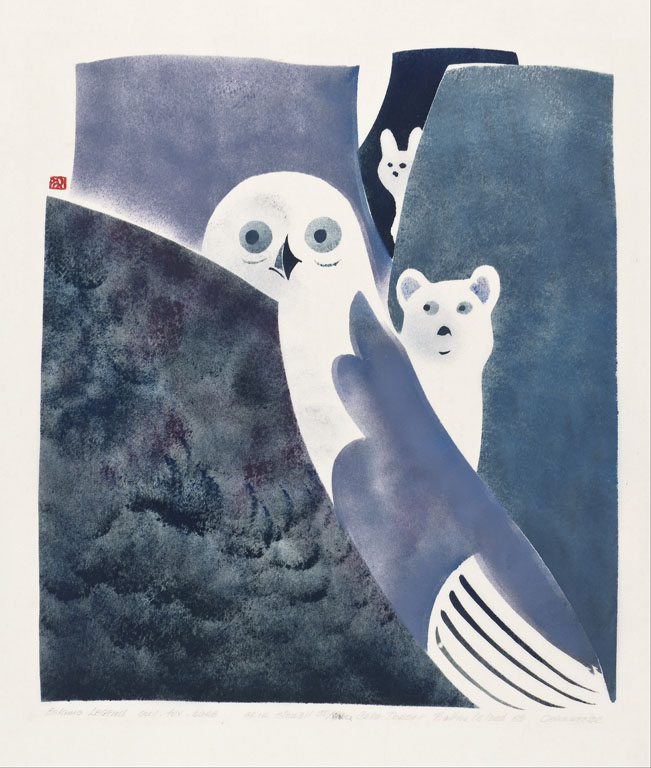

© Canadian Museum of History, Owl, Fox and Hare Legend, Osuitok Ipeelee, 1959, CD 1959-021 SS, photo Marie-Louise Deruaz, IMG2010-0207-0037-Dm.jpg.

The remarkable story of this artistic encounter and its extraordinary result are the focus of Inuit Prints – Japanese Inspiration, one of the Canadian Museum of History’s travelling exhibitions, which is currently being presented at the Musée des beaux-arts de Sherbrooke.

Excerpt from “Introduction: Early Printmaking in Cape Dorset”

By Dr. Norman Vorano

[…]

The 1950s and 1960s were turbulent times for Inuit across the Eastern Arctic, and the print studio served a great variety of needs. With the market for fox pelts in steep decline, many Inuit began to move away from a subsistence life in camps (where they predominantly depended upon hunting for food and fur trapping for trade goods) and took up permanent residence in the rapidly growing settlements, which offered opportunities for education, healthcare and employment. Reflecting upon his own transition into community life, artist Kananginak Pootoogook recalled that he moved into Cape Dorset in 1957, when his aging father, Joseph Pootoogook, required ongoing medical attention. To support his growing family, Kananginak found steady employment in the crafts studio, first as a maintenance worker and then as a printer. For many like him, the crafts studio provided a formalized yet flexible setting for employment and small-scale entrepreneurship through the sale of arts and crafts. Art was embraced because it met the people’s changing social and economic needs, as well as their desire to remember a way of life that seemed to be rapidly disappearing.

The fall of 1958 was a pivotal time for the Cape Dorset print program. The printmakers assembled a collection of graphics based largely on their own drawings, published in editions of thirty. Known retrospectively as the “experimental” or “uncatalogued” collection, it was said to have numbered up to twenty different stonecut or linocut prints, with some evidence of brayer stencilling[i] (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 in the image gallery). Thirteen of these new prints were put on sale on December 12, 1958 at the Hudson’s Bay Company department store in Winnipeg.[ii] The sale was a success and generated a positive reaction, with the Winnipeg Free Press reporting that the prints were “close in design to the now world-famous Eskimo sculpture.” [iii]Casual sales—largely undocumented today—of these experimental prints continued into early 1959 at Canadian Handicrafts Guild outlets in Montreal and Toronto.[iv]

- Three Caribou, dated November 20, 1957, was one of the first prints made in the Cape Dorset studio. The printmaker, Kananginak Pootoogook, recalled his growing frustration when the stone block kept breaking under his chisel.

- The artists attempted a variety of experiments, including frottage, for background.

- In the experimental Cape Dorset prints, colours were uniformly applied, image sizes were small and editions were limited to thirty copies. In this case, stonecut was used to create the black lines, and stencil was used for the blue background

- “This was from a drawing by [Joseph] Pootoogook. These buckets for carrying cold water, if they were made from bearded sealskin, would be called qaptauga.” – Kananginak Pootoogook.

Ironically, this taste of success prompted [Canadian artist James] Houston’s superiors at the Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources to put a temporary halt on the distribution of prints. Eyeing greater potential, the department revised its marketing strategy and decided to retail prints through higher-end art galleries with carefully staged annual releases, rather than selling them through department stores. The early experimental prints were removed from circulation and the studio began afresh, directing its energies towards the completion of its first annual collection, which was to be officially released later that year (the collection was eventually released in February 1960). This set the stage for the final transformation of the Cape Dorset crafts shop into a fine art print studio. But one element was missing: the influence of “Japan, the land of prints.”[v]

Although Houston had studied art at the Ontario College of Art and the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris, he had, by his own admission, relatively limited printmaking experience when he began working in Cape Dorset.[vi] Wanting to bring a greater knowledge of printmaking to the Arctic, in the fall of 1958 he used his accumulated leave to travel to Japan in order to study woodblock printmaking with Un’ichi Hiratsuka, one of Japan’s most revered print artists of the twentieth century[vii]. While in Japan, Houston met with and learned from many other Japanese artists, including Shikō Munakata, Shōji Hamada, Keisuke Serizawa, Kichiemon Okamura, Sadao Watanabe and Yoshitoshi Mori, as well as the Muraoka family—three generations of traditional doll-makers. He witnessed first-hand Japan’s flourishing mingei (folk crafts) movement, meeting its principal philosopher, the famous Sōetsu Yanagi, and gave public and private lectures on Inuit art, including a black-tie presentation to Japan’s Prince Mikasa. After a rewarding three-month trip, Houston returned to the Arctic in the spring of 1959 and shared what he had learned in Japan with the Cape Dorset printmakers. He brought specially made Japanese printmaking tools and washi (handmade paper) to Cape Dorset, as well as a collection of Japanese woodcut and kappazuri (stencil) prints created by some of Japan’s greatest modern print artists. […].

Over the spring and summer of 1959 the Cape Dorset studio blossomed. Buoyed by the artistic and technical possibilities seen in the Japanese prints (not to mention the tantalizing spark of public interest after the first Winnipeg sale), the Inuit printmakers began producing more technically sophisticated, larger and more aesthetically accomplished prints. They were inspired by the powerful and expressive sumizuri (black ink prints on white paper) by Un’ichi Hiratsuka and Shikō Munakata, the flowing colours in Kichiemon Okamura’s kappazuri prints, and the creative use of negative shape (unprinted surface) in Yoshitoshi Mori’s works. Yet the Cape Dorset printmakers did not slavishly imitate Japanese artists. Endlessly inventive bricoleurs, they selectively borrowed from their far-flung sources, adapting and modifying the practices, tools, techniques and stylistic elements that best reinforced their own aesthetic and cultural values. Perhaps most importantly, the first five Inuit printmakers—Osuitok Ipeelee, Iyola Kingwatsiak, Eegyvudluk Pootoogook, Kananginak Pootoogook and Lukta Qiatsuk—actively improvised and adapted along the way. Their determination, resourcefulness, willingness to experiment and ability to absorb remarkably cosmopolitan influences are a testament to their creativity, imagination and self-confidence. These qualities have been hallmarks of the Cape Dorset studio for over five decades.

[…] End of excerpt.

In our next post, Canadian Museum of History Paper Conservator Amanda Gould will tell the story behind washi, one of the key materials used in many of the Cape Dorset prints, and the role it plays in conserving our National Collection.

References:

[i] For the North American perception of Japan as “the land of prints,” see Alicia Volk, “Japanese Prints Go Global: Sōsaku Hanga in an International Context,” in Made in Japan: The Postwar Creative Print Movement, ed. Alicia Volk (Milwaukee, WI: Milwaukee Art Museum, 2005): 5-21.

[ii] See Mary D. Kierstead, “Profiles: James Houston,” The New Yorker (August 29, 1988): 34. Note: Ontario College of Art curriculum from the late 1940s included lithograph and etching classes but not woodblock printing.

[iii] All names follow the Western order: the given name preceding the family name.

[iv] See Sandra Barz, Inuit Artists Print Workbook, Vol. III, Book 2 (New York, NY: Arts and Culture of the North, 2004): 358-61.

[v] Incidentally, Houston made the final arrangements for this sale in October 1958 while stopping over in Winnipeg en route to Japan to study with Un’ichi Hiratsuka.

[vi] Winnipeg Free Press (Saturday December 13, 1958): 42.

[vii] Little is known of the early distribution. See the advertisement: “Eskimo Carvings and Stone Cut Prints Direct from the Arctic, on February 23.” The Globe and Mail (Toronto) (February 21, 1959): 15.