Accessibility and Inclusiveness: Evolving Resources for People Impacted by Blindness

The Canadian National Institute for the Blind (CNIB) Foundation’s collection sheds light on the ongoing creativity of designers who enable everyone to interact autonomously with the world. In 2020, the Canadian Museum of History acquired this collection of 101 objects. It showcases just over a century of progress in the resources and tools available to people impacted by blindness. Ingenuity is the name of the game to facilitate access to information, communicate more effectively, get around safely, or simply have fun.

This collection includes Braille learning tools, talking book reading devices, canes, and Braille games.

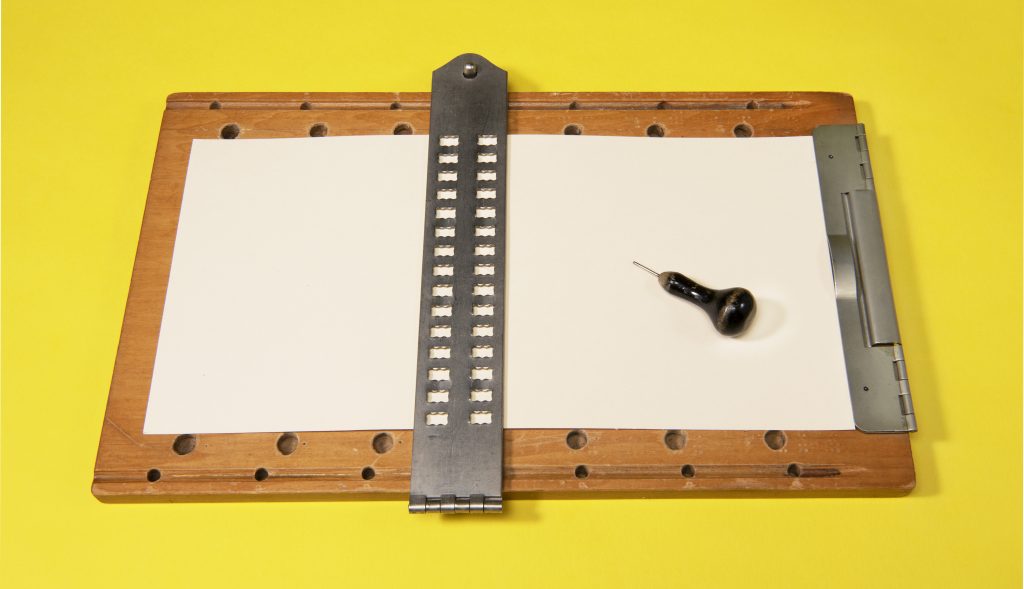

Braille tablet and stylus. Canadian Museum of History, 2018.251.20.

Blindness in Canada

The 2017 Canadian Disability Survey revealed that approximately 1.5 million Canadians are living with sight loss. A further 5.59 million people suffer from eye diseases that can lead to sight loss. Sight loss is unique to each person, ranging from a partial loss impacting daily activities to total blindness. Today, a range of inclusive programs and resources are available to meet these individuals’ various needs and realities.

In the early 20th century, however, things were rather different. There were resources available to help people impacted by blindness gain independence, but they were still underdeveloped, disparate, and difficult to access. To remedy this, individuals mobilized themselves and used their creativity to improve the situation.

The First Objective: Facilitating Access to Reading

The CNIB Foundation is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing programs and technologies to Canadians who are blind or partially sighted. Since its inception, the Foundation has been dedicated to reducing barriers and continually innovating to ensure all people in Canada are given the opportunity to live life by their design.

Stamp from the Free Library for the Blind. Circa 1907. Canadian Museum of History, 2021.251.1.

The CNIB Foundation’s origins date back to the establishment of the Canadian Free Library for the Blind (CFLB) in 1906. As its name suggests, this organization was set up to provide free embossed reading material to blind or partially sighted people across the country. In those days, few readers with sight loss could afford these expensive tomes. Otherwise, this type of resource was mainly available in the few schools for the blind. Once they finished school, they no longer had the same easy access to books and other adapted technologies. Therefore, the CFLB played a key role in the lives of many people living in Canada.

Incorporation of the CNIB Foundation

Over time, the CFLB evolved beyond book lending. The Library also supported its members in learning to read and write raised text, provided expensive reading and writing technologies, and helped people with sight loss find employment.

Braille typewriter designed by David Abraham. 1950-1980. Canadian Museum of History, 2018.251.21.2.

The increasing rate of blindness in Canada caused by the Halifax explosion in 1917 and the return of veterans from the First World War ― some of whom had lost their sight partially or completely ― raised public and government awareness of the need for organized social services for people with sight loss. As a result, the CNIB Foundation was incorporated in 1918 by seven members of the CFLB Board of Directors, including veterans. It thus formalized the scope of its mandate, as a champion of the interests of people living with some form of blindness, to implement innovative programs.

Recognition of the Rights of Blind and Partially Sighted People

After the Second World War, the Canadian social context increasingly favoured the autonomy and inclusion of blind and partially sighted people. Indeed, the introduction of social programs supported by various levels of government to protect vulnerable populations, such as health insurance and universal old-age pensions, provided a stronger safety net than ever before. Moreover, the rise of activism to assert the rights of disabled people made it easier for those with sight loss to integrate into society. Together, these measures offered more opportunities for development according to individual interests, in addition to a minimum subsistence level for those in need.

Technology and Autonomy

From the 1980s onwards, in addition to a more inclusive social context, a new set of digital tools and devices made their way into Canadian homes. Eventually, computers and cell phones, among other technologies, became an integral part of our lives. For people impacted by blindness, these technological advances have become more than a convenience: they dramatically improve access to reading, literacy, and, above all, independence.

From “Talking Books” to Audiobooks: An Example of Inclusive Technology

Did you know that one of the biggest, most diversified and lucrative industries today is audiobook production? The first “talking books” were specifically designed to make reading accessible to people with sight loss. Since the advent of digital formats and streaming services, the consumption of audiobooks has grown exponentially, both among the blind or partially sighted and the sighted.

Three models of audiobook players. Canadian Museum of History, 2018.251.

Lastly, since the beginning of the 20th century, initiatives have been developed to try and integrate the needs of people with disabilities into society. Turning this philosophy into a reality remains a challenge. Nevertheless, efforts to understand the needs of people who are blind or partially sighted are made on an ongoing basis, and inclusive technologies make these barriers easier to overcome. The CNIB Foundation’s collection is an interesting avenue to discover more about the subject.

Chloé Ouellet-Riendeau

Chloé Ouellet-Riendeau is Assistant Curator, Sports History at the Canadian Museum of History. Her interest in this field lies mainly in the ways in which this history is combined with the social and political movements of the time and the agency of its participants.