Origins of a Collection

When ethnologist Marius Barbeau (1884–1969) acquired this collection in 1933, his research goals were quite different than the ones we have today.

At the time, Barbeau was engaged in ongoing study of the Aboriginal cultures of northern British Columbia and the Yukon. During the late 1920s, when he was at Arrandale in northern British Columbia, he heard a Japanese melody being played on a phonograph, and was struck by how closely it resembled certain songs he had just collected among First Peoples. In December 1932, keen to pursue this new line of enquiry into the possible Asian origins of Canada's First Peoples, he contacted an authority on Chinese songs: Professor Kiang Kang-Hu, then Chairman of the Department of Chinese Studies at Montreal's McGill University.

For four days, Kiang and Barbeau analyzed some twenty transcriptions of songs collected among Aboriginal peoples of British Columbia and the Yukon. The results were intriguing. Professor Kiang found numerous similarities between the Aboriginal songs and certain archaic types of Chinese song. The scholars further pursued their comparison of Chinese and Aboriginal music by listening to a small collection of Chinese records borrowed from a Chinese shopkeeper in Montreal. Once again, they noted remarkable similarities between the structures of certain songs. For example, a song from the Gitksan of Bear Lake, "Kalastetsee", recorded by James Teit, was very similar to the Chinese "The Song of Blue-Chamber". They also discerned these same structures in several of the recordings they'd borrowed from the shopkeeper, particularly in a piece called "The Old Lady Worships".

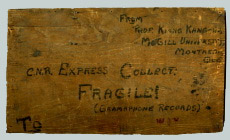

Although still somewhat preliminary, their research attracted the attention of newspapers, including The Montreal Gazette which featured a story on their work on December 14, 1932. Intrigued by what they had discovered so far, Barbeau was eager to continue his research. Having learned that the Chinese shopkeeper had gone bankrupt and was offering to sell his collection of records at $3.00 per dozen, Barbeau and Kiang struck an agreement to purchase some of the recordings for the National Museum of Canada (today the Canadian Museum of Civilization). Professor Kiang chose more than 200 different records from the 1,500 offered by the shopkeeper. With the help of his children, Kiang prepared a bundle of 22 dozen records (264), tied up with string in groups of two to four records. The entire package, costing $66.00 plus $3.00 shipping, was sent to Barbeau on March 21, 1933.

For a while, Marius Barbeau continued his enquiries, replaying certain recordings in order to note similarities in music, melody and rhythm to Aboriginal songs. Soon, however, his research would take him in another direction, and the collection of recordings fell into an oblivion so complete that the disks did not resurface until 2008, following a silence of 75 years.

Frozen in time, the records were still in their original sleeves, still tied together in groups with various bits of twine — just as they had been packaged in 1933 by Professor Kiang and his children for Marius Barbeau.

This time around, we have a completely different kind of interest in this collection. Recordings like these, showcasing traditional Cantonese opera from 1915 to 1920, are now extremely rare. Very few collections of this sort have survived down through the years. This is particularly true of Canadian recordings such as these, which were produced by the Berliner Gram-o-phone Co. Limited, later known as the Victor Talking Machine Company of Canada Ltd. in Montreal, as well as the Toronto subsidiary of Columbia Records. Of the initial 1933 collection of 264 recordings, 238 remain. Of these, fifteen are unfortunately broken or otherwise damaged.