After the Conquest, the British quickly realized that they could not govern Canada without the cooperation of the French-speaking population.

The government in London hoped to turn Canadiens into English-speaking Protestants. But a tiny British minority could not impose their language, religion and culture on the Canadien majority. To govern effectively, British officials in Canada had to respect the reality of a Catholic, French-speaking population.

Pragmatic Governance

Faced with governing a colony that was still overwhelmingly French-speaking, the colonial government communicated with Canadiens in French. British governors quietly ignored the law preventing Catholics from holding public office. Many Canadien public servants continued to work for the new government. Courts continued to use French civil law, along with British criminal law.

“Barring a Catastrophe shocking to think of, this Country must to the end of Time be peopled by the Canadian race.”

– Sir Guy Carleton, Governor General of British North America, 1767

The Quebec Act

The Quebec Act recognized the pragmatic, and necessary, accommodations made by British officials in Canada. Henceforth, Catholics could hold public office. French civil law regained its official status. The Catholic Church could return to collecting tithes, or religious taxes, from parishioners. The French landholding system remained unchanged.

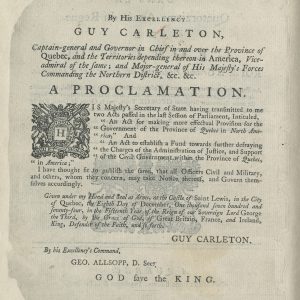

Sir Guy Carleton

Carleton, a strong supporter of the Quebec Act, governed the British province of Quebec between 1766 and 1778.

Gabriel-Elzéar Taschereau

Taschereau, who fought against the British at Québec City in 1759, made a successful career in the British administration.

The St. Lawrence River at Québec City

In the painting below, a red-coated British officer sits at the edge of the cliffs overlooking the St. Lawrence River, sketching the scene. Once a theatre of war, the river is now a quiet waterway linking Canada to the rest of the British Empire.

British Immigrants

Some Britons settled in Canada during and soon after the Conquest, creating the St. Lawrence valley’s first English-speaking communities. Others moved on to other parts of the British Empire in North America. All shared the experience of living as English-speakers within a mostly French-speaking population, and living in a region where First Peoples were important allies and trading partners.

John Caldwell

Following the Conquest, former First People allies of the French sought to strengthen their ties to the Crown by adopting British officers, including Lieutenant John Caldwell. Caldwell himself believed that the adoption ceremony had made him a chief, rather than a family member.

Signs of adoption

John Caldwell likely received these items, along with the other ornaments and clothing he wears in his portrait, when he was adopted by the Anishinabe (Ojibwa).

James Thompson

James Thompson arrived in Canada as a sergeant in the 78th Regiment (Fraser’s Highlanders) during the Seven Years’ War.

After the war, he remained in the colony as a civil engineer. Thompson’s work brought him into close contact with Canadiens. He learned French, made many Canadien friends and married a Canadienne – who died, along with their six children, before 1775. Nonetheless, he remained very much an English-speaking Protestant.

James Thompson’s Dirk

Dirks were Scottish daggers, worn with both military and civilian highland dress.

Frances Brooke

Frances Brooke wrote Canada’s first novel, The History of Emily Montague. Brooke moved to Québec City in 1763 to join her husband, a military chaplain. They remained until 1768.

A novel of manners, Emily Montague was more concerned with sense and sensibility than conquest and occupation. But it provided a vivid portrait of life in a small British society within Canada.

Photo at top of page:

A View of the Basin of Quebec

James Hunter, 1779

Library and Archives Canada, 1989-246-3