FULL TOUR

The Design

Process - CHALLENGES

Given all the diverse sources of

information, the challenge of the design process can well be

imagined. The museum would be a complex, interrelated set of

diverse functions; the architectural programme characterized it

as "simultaneously a shopping plaza for ideas, a layman's

college, a hospital for artifacts, a heritage temple, and an

entertainment centre". Some spaces would require maximum

creative architectural expression; others, maximum restraint.

Some would be detailed, sophisticated environments carefully

fitted to precise functions, others would have to be highly

flexible.

A plan showing the second level of the

museum - both the public and the curatorial wings.

© Canadian Museum of Civilization,

D2004-18578, CD2004-1376

|

The architect saw the design process as beginning from the

inside and expanding outward. First, the inner functions of the

museum were studied and understood, a shape assigned to each

function, and a building shell wrapped around them. The

translation of a textual programme into a three-dimensional

building, with vertical as well as horizontal relationships

between areas, prompted changes from the original

specifications, in an effort to reconcile competing needs for

adjacencies.

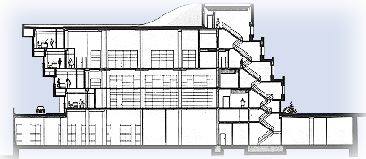

The curatorial wing.

© Douglas J. Cardinal Architect Ltd.

|

Above all, building design had to meet the needs of the

collections, the core resource of CMC. This meant environmental

conditions suitable to the long-term preservation of artifacts,

whether in storage or exhibition galleries. The building

structure had to be capable of maintaining those conditions in a

climate which has extreme temperature fluctuations. The

collections need protection from theft, fire, or other dangers,

and functional adjacencies conducive to effective management.

CMC's custom-designed collections storage

furniture stands two storeys high, with grating installed to

provide a mezzanine floor. Although basically an open-faced

shelving, the furniture is highly adaptable - drawers can

be fitted in, for example.

© Canadian Museum of Civilization,

D2004-23607 (left),

D2004-23608 (right), CD2004-1378

|

Artifacts require specialized, stable environments to prevent

their physical deterioration. Some are highly sensitive to

light, which can cause cumulative and irreversible damage. The

traditional response of museums to this problem is to reduce the

duration of exposure and level of light in collections holding

areas, and to create 'black-box' galleries in which filtered

light is used in restricted amounts. Natural light is less

easily controlled. This presented a problem for Cardinal, who

had relied on the use of natural light in his previous buildings

to make them vital and stimulating places. Furthermore it was

desirable that the new museum have some natural light to combat

'museum fatigue' to which visitors become prone in black-box

galleries, owing to a lack of visual orientation and

stimulation. Advantage also had to be taken of the scenic views

offered by the site.

CMC's simple circulation route, and

periodic views to the outside, help keep visitors from becoming

disoriented.

© Canadian Museum of Civilization, D2004-18592, CD2004-1377

|

|

The issue of natural light exemplifies a key problem facing the

design of museums: are they to be "artifact-friendly" or

"people-friendly"? Sometimes the provision of maximum

protection for the artifacts and as much public exposure as

possible of the artifacts seem mutually incompatible.

In designing the museum for public use, Cardinal was instructed

to ensure facilities and amenities catered to the safety,

comfort, and pleasure of visitors. There was to be direct and

easy access to public areas for all, and the building should

encourage visitors to enter off Laurier Street. Exhibition

galleries had to accommodate large numbers of visitors,

circulating at their own speeds, without congestion or

overcrowding at any point. The circulation route was to permit

visitors to avoid travelling through exhibitions of no interest

to them or retracing their steps to re-enter central areas. Also

important was that the building's architecture be a symbol of

national pride and identity, and convey the image of an active

and dynamic institution, so that it attract tourists from the

Ottawa side of the river and draw tourists to the capital

expressly to see the museum.

Once the requirements of CMC's staff had been satisfied, the

next step of the design process was to apply external factors to

the shell, further shaping it to the needs of the site and

larger context of the Ottawa River basin. The building was to

give Laurier Street greater dignity as part of the ceremonial

route; on the other hand its street facade had to make the

museum look inviting to passers-by, by providing bustle and

colour. Both this and the park side of the museum were to

provide a degree of transparency, to give visitors an idea of

what awaited them within. The site itself had to be an

attractive, hospitable, and dynamic place, with the building

providing a framework bounding and protecting special areas of

public activities. Above-ground parking was to be avoided, as an

unattractive feature; this, together with the satisfactory

integration of group arrivals and departures with the internal

functions of the museum, proved one of the most persistent

challenges during design.

CMC is linked with Canada's political

centre - the Parliament Buildings - by view-lines

which have a ritual symbolism.

© Canadian Museum of Civilization, D2004-23611, CD2004-1378

|

|

It was important to ensure the building not act as a barrier. It

was not to obstruct access to Parc Laurier, making it clear that

site events were public activities to be freely attended by

anyone who so wished. It was not to form an apparent wall

between Gatineau and the river, and the building height should

not extend too high above street level. Nor was it to intrude on

a public corridor fronting the river and the recreational trail

there. Most importantly, both interior and exterior elements of

the building were to protect or enhance certain views of the

river and of Parliament Hill. The view-cones that the National

Capital Commission delineated, and their intersection,

influenced the shaping of the museum's form. Furthermore, the

architectural character of the building was to make it easily

identifiable as a major tourist attraction. Since the site was

low, special attention was to be given to making roofs -

highly visible from Parliament Hill, Nepean Point, the Alexandra

Bridge, and high-rises in downtown Gatineau - distinctive

and interesting.

|