(Page 2 of 2)

Housefront Housefront

Paintings Paintings

Carved Interior Carved Interior

Poles and Posts Poles and Posts

Interior Screens, Interior Screens,

Housepits, and Housepits, and

Smokeholes Smokeholes

|

The terms applied to a house's structural members are the same as for the bones of a human skeleton, or more specifically the bones of the collective ancestor. The two front vertical support posts are the arm bones, the two rear posts are the leg bones, the longitudinal beams are the backbone, the rafters are the ribs, and the exterior cladding is the skin. The inhabitants are the spirit force of the ancestor/house.

In addition to being a place of shelter, the house had a cosmological meaning for the Haida, who thought of the house as a very large box and often decorated its walls to coincide with the images used on boxes. The concept of boxes within boxes is central to Haida beliefs about containers and the spiritual beings who safeguard their precious contents.

The wealth contained by the house-sized box was in the form of human souls. The Haida believed that the fish stored in food boxes retained their souls until they were consumed, when their souls were released to become new fish and continue the cycle. Similarly, a house protected the souls of its inhabitants until they died, whereby their souls were released to newborn members of the family. The Haida were always concerned to know which child had inherited the soul of a recently deceased relative and would search the faces and actions of the newborn to determine that affiliation. The deceased were placed in burial boxes in mortuary houses or on posts, as close as tolerable to the house of their surviving kin. Reverend William H. Collison comments on this after his first night in a house at Masset village:

When opening my door the following morning, I was startled at receiving a smart lash as though from a whip on the side of my face. Looking up to see the cause, I perceived that the wind had blown the side out of a mortuary chest, which was supported by two great posts. In this receptacle lay the skeleton of a woman, her long black hair was being blown to and fro by the wind as it hung down fully three feet from the scalp.

|

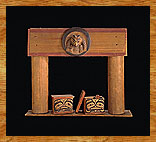

This model of a double-post mortuary made by Charles Edenshaw contains two burial chests with model corpses inside. The crest of the Bear in a nest belongs to a chief of Skedans village. On the actual mortuary, the Bear is holding the chief's copper this original front panel is now in the Museum of Northern British Columbia in Prince Rupert.

Collected at Masset between 1895 and 1901 by Charles F. Newcombe.

CMC VII-B-661 (S92-4243) |

|

This central panel from a double-post mortuary in Skidegate village portrays Grizzly Bear with a protruding tongue and prominent ears.

Collected circa 1900 by Charles F. Newcombe.

CMC VII-B-668 (S92-4246) |

The Haida viewed the universe as a large house (the World Box or World House), with the sides being the four cardinal directions. After the Raven brought the sun to this World Box from another box in the house of the Sky Chief, the sun entered the World House each day and passed over its roof at night. The stars were sunlight shining through holes in roof of the World House. The seasons were tracked by marking the position of the sun at daybreak on the wall opposite the hole where the sunlight entered.

Through the middle of each house ran an axis that centred the resident family at the centre of the world, where the contact between the various levels of the universe was the greatest. The smoke from the household fire signified this axis of conjunction of various worlds and was the site of daily prayers to the supernatural forces that determined people's destiny. The houses of important chiefs had a succession of box-shaped pits extending symbolically down into the underworld. The living compartment of the chief was like a smaller box at the back of the house.

Not a single complete original Haida dwelling survives, but there are historical photographs of about four hundred Haida houses in twenty-five villages, taken in the last half of the nineteenth century. In addition, nearly one hundred house models survive in museum collections. The Field Museum in Chicago has the entire village of Skidegate, some thirty houses in model form, commissioned by James Deans for the Columbian World Exposition in Chicago in 1893.

Deans spent considerable time in Skidegate in the 1880s and was able to recruit craftsmen from each lineage group to make models of the houses connected to their families. It must have been a terrific undertaking on his part to negotiate the rights, fees, and schedules of so many artists to deliver the complete model within a year. The model even has carvings of figures engaged in various rituals from funeral ceremonies to potlatches, and the house belonging to Chief Skidegate includes a detailed reconstruction of the interior house pit.

Another excellent piece that is part of the model of Skidegate village is the mortuary that stood behind Chief Skidegate's house. It is a shedlike building with a painted housefront depicting a Wasgo (or Sea Wolf) that once lived in a lake behind Skidegate. When its roof is removed, stacks of burial chests are revealed, including the highly decorated ones of former Chiefs Skidegate resting on a huge carving of a Wasgo. Such supports (called manda'a by the Haida) were often placed at the foot of the mortuary post to which the chief's burial box was moved two years after his death. Many of these carved supports can be seen in historical photos of Haida villages.

|