A Silk Robe and Ten Thousand Porcelain Dishes: Links Between Early Canada and Asia

Chinese export porcelain cup and saucer found at the wreck site of the Machault, a French ship that sank in the Restigouche River estuary (Quebec) in 1760. On loan from Parks Canada.

In 1634, French explorer Jean Nicollet carried “a robe of Chinese damask, adorned with flowers and multi-coloured birds” on his journey to the Great Lakes, apparently to ensure that he had something appropriate to wear should he reach China and encounter subjects of the Chongzhen Emperor. This anecdote, which will be familiar to readers who have seen it retold in a classic Heritage Minute, can be read as evidence of colonial foolishness. Silly explorers.

Yet, as the curator responsible for the history of New France at the Canadian Museum of History, I would prefer examining how this explorer’s expectations and startling apparel hint at something more serious and fascinating: the ways in which Canada and Asia were entangled centuries before the conventional Asian-Canadian historical narrative begins.

The more familiar story of immigration and integration begins with mid-19th-century gold rushes and railways, laundries and restaurants, and stretches into a 20th century marked by exclusionary policies and internments, struggles for inclusion, and modern multiculturalism. It’s a powerful, worthwhile story. But it’s also one onto which we might graft a preface of sorts, by offering a few glimpses of the ways in which, from the 16th to the late 18th centuries, consumer goods brought distant peoples into indirect contact with one another.

The Quest for Asia

Canada was, in a sense, a stumbling block on the journey from Europe to Asia. Not, of course, for the Indigenous Peoples who had inhabited this land for many millennia before contact with Europeans, but for the explorers and their sponsors whose core ambition was finding a shortcut to the riches of the Far East. Europe craved the luxury consumer goods that had, since antiquity, made their way overland along the fabled Silk Route — goods that, in the 15th century, the Portuguese had begun to transport by ship via the Indian Ocean and African coast. Christopher Columbus was not alone in seeking an alternative westward route. So, too, in more northerly latitudes, did the likes of John Cabot, Jacques Cartier, Martin Frobisher, and Samuel de Champlain.

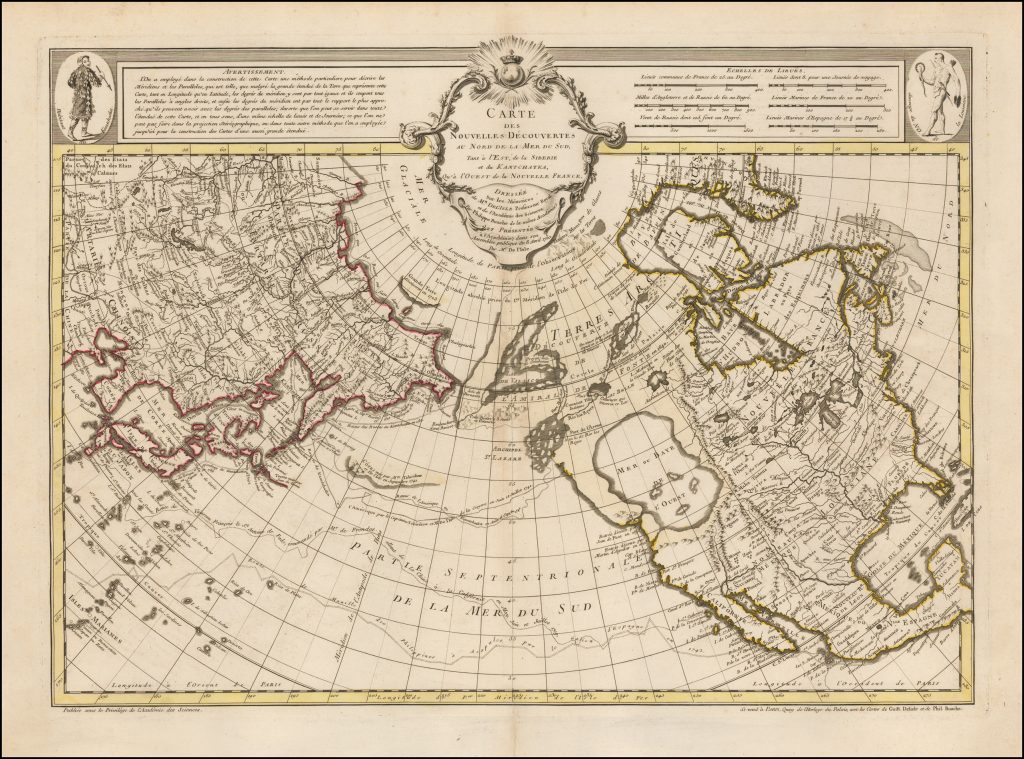

This mid-18th century map prepared by Philippe Buache, first geographer to the King of France, shows “Mer ou Baye de l’Ouest” (Western Sea or Bay), an imaginary shortcut to the Pacific Ocean and Asia. Carte des nouvelles découvertes au nord de la Mer de Sud, tant à l’est de la Sibérie et du Kamtchatcka, qu’à l’ouest de la Nouvelle France (“Map of new discoveries north of the South Sea, both east of Siberia and Kamchatka, and west of New France…” 1750).

The context within which Champlain dispatched Nicollet was the expansion of the fur trading network among Indigenous Peoples and the search for an elusive route to Asia, which went hand in hand. It was also a context influenced by the presence of global players. Nicollet most likely obtained his robe of Chinese silk from the Jesuit missionaries who arrived in Canada around this time. The Jesuits had already been active for several decades in China, Japan and South Asia, and their missionary experiences in those parts of the world would inform, in small but noticeable ways, their efforts in early Canada. For example, the Jesuits called their Wendat and Haundenosaunee lay helpers dogiques — a term derived not from the usual Latin roots, but from the Japanese word, dôjuku.

Although Indigenous informants made it increasingly clear that there was no navigable shortcut to the Pacific Ocean, explorers and cartographers kept grasping in vain at an imaginary Northern or Western Sea that would open up a way to the Pacific. Well into the 19th century, the search for an elusive Northwest Passage through the ice of Canada’s Arctic would preoccupy optimistic geographers and adventurous mariners.

Early Canada as a Market

In the absence of a westward shortcut to Asia, Europeans intensified their eastward sea trade, launching an unprecedented phase in the history of global commerce. The Dutch, English — and eventually French — each founded their own East India Companies, importing large quantities of spices such as pepper, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg and mace, along with tea and coffee, and a variety of silk and cotton textiles.

![Exchanges between Asia and Canada were not unidirectional: as early as the 1720s, Canadian ginseng was exported to China. Illustration taken from Mémoire [...] concernant la précieuse plante du gin-seng de Tartarie, découverte en Canada par le P. Joseph Francois Lafitau (1718).](https://www.historymuseum.ca/blog/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Laureliana_de_Canada_en_chinois_gin-seng_en_iroquois_garent-oguen-1024x920.jpg)

Exchanges between Asia and Canada were not unidirectional: as early as the 1720s, Canadian ginseng was exported to China. Illustration taken from Mémoire […] concernant la précieuse plante du gin-seng de Tartarie, découverte en Canada par le P. Joseph Francois Lafitau (1718).

Among Asian exports, porcelain stands out in quantity and in documentation — such as the probate inventories that listed a household’s material possessions — as well as in the ground. A single small fragment of Chinese porcelain has been found on the site of the Habitation, or trading post, at Québec City, dating to the earliest decades of the French settlement. Champlain may well have sipped from it while daydreaming about a route to China.

Blue-and-White Gold

It is easy to underestimate just how revolutionary porcelain — the stuff of kitchen floors and toilets nowadays — was at the time. Its exceptional qualities come from the fact that its clay allows firing at a very high temperature, resulting in a translucent and watertight glass-like surface that, in an era before plastics, was unmatched in its jewel-like appeal. Porcelain’s much-loved classic palette was blue and white for the simple reason that cobalt, which provided the blue colour, was the pigment best able to withstand high firing temperatures.

Dutch earthenware dish with blue floral decoration unearthed in Québec City, dating from the early 18th century. On loan from the ministère de la Culture et des Communications du Québec.

Porcelain was a Chinese invention, and long remained a closely guarded trade secret. The industry was centred on the city of Jingdezhen and exported via the port of Guangzhou, known to Europeans as Canton. Knowledge of porcelain also spread to Japan, but Japanese production of porcelain for export remained comparatively small.

Only in the 18th century did Europeans succeed in producing porcelain of their own — and, even then, it took them about a century to match Asia’s output in quality and quantity. In the meantime, Europeans produced an abundance of tin-glazed earthenware, called faïence or delftware, that imitated the blue-on-white designs of Asian exports. Europeans took to joking, as well, about the maladie de porcelaine (“porcelain fever”), referring to the wild enthusiasm with which certain collectors sought out the real thing.

Chinese export porcelain cup and saucer in a style known as Batavian ware. The cartouches were originally decorated with enameled designs, which here have been damaged by the elements. Found on the site of the Machault, sunk in 1760. On loan from Parks Canada.

In addition to having been imported in large quantities to New France, porcelain also has the merit of not deteriorating even in otherwise harmful environments. At Louisbourg on Cape Breton — a fortified port town founded a century after Québec City’s Habitation and occupied for only four decades —archaeologists have unearthed more than 70,000 fragments of Chinese-produced porcelain. Fragments have also been found at French fort sites across the Great Lakes and the Mississippi Valley, as well as on the sites of English fishing ports in Newfoundland, and trading posts on Hudson Bay.

We Have Always Been Global

Nicollet’s Chinese silk robe has long been lost to history, remembered only in a single sentence in a book from the period. However, attentive visitors to the Museum of History’s Canadian History Hall can see a few examples of 18th century Chinese export porcelain found at Louisbourg, Hudson Bay, and at the bottom of the Restigouche River’s estuary. They will see European faïence on display as well, and get a feel for the ways in which Asian aesthetics became an inspiration. Early Canada may have been an ocean away from Europe, on the imperial periphery, but it was nonetheless thoroughly well connected to world markets and global tastes.

Jean-François Lozier

Jean-François Lozier is Curator of French-American History at the Canadian Museum of History. His research centres on Franco-Indigenous relations, also the topic of his book, Flesh Reborn: The Saint Lawrence Valley Mission Settlements through the Seventeenth Century (McGill–Queen’s University Press, 2018), as well as on the material culture of the 17th to 19th centuries.