Fan Rituals: A Part of Hockey History

As the 2017 Stanley Cup Playoffs are underway, the beards of your favourite NHL players are growing longer. The ritual of growing a playoff beard in the postseason is popularly believed to have begun with Denis Potvin, Clark Gillies and their teammates on the New York Islanders in the 1980s. Over time, this ritual has come to mark success in the post-season. The longer the beard, the deeper the run of player and team. Some fans have adopted this ritual to show their support for a team, and to participate vicariously in the playoffs.

Many other signature NHL playoff rituals are driven by fans. As early as the 1950s, newspapers reported that hockey fans threw items on the ice to intimidate opposing teams, or to protest a referee’s call. In 1955, fans threw shoes and galoshes on the ice during a Canadiens game in Montréal to protest NHL President Clarence Campbell’s recent decision to suspend Maurice Richard for the rest of the NHL season. A riot erupted outside the Montréal Forum, where Campbell attended the game. Visitors to the Hockey exhibition can see a can of “Rocket” Richard soup created to protest Campbell’s decision.

One of the most curious (and gross) examples of fans throwing items comes from Detroit, where fans are known to throw octopuses on the ice. The original octopus-pitcher was Jerry Cusimano. In 1952, Jerry and his brother Pete hoped that Detroit would win the 1952 Stanley Cup in eight consecutive games in the final two series. The team had swept the semi-finals, and were ahead of Montréal in the finals. Jerry came up with the idea of throwing an octopus on the ice for good luck. Eight legs, eight wins in a row.

Legendary sports reporters Dick Beddoes and Scott Young reported on the octopus-pitchers for the Toronto Globe and Mail in the 1960s and 1970s. They learned that Cusimano got the octopus from the family seafood business, snuck it into the Detroit Olympia arena for Games 3 and 4, and flung it onto the ice. As you can imagine, the on-ice officials were not impressed. The Wings won the eight consecutive games, however, and the Cup. In a 1961 interview, Cusimano revealed that he carried the octopus to the games in bagpipes. Originally, the octopuses were brought to games in a bowling bag, but Cusimano once grabbed the wrong bag on his way to the arena. Successfully in, his technique was to wait for an exciting movement, then pitch the octopus onto the ice.

Cusimano delighted in this ritual. He told a reporter: “They never notice when I unzip the thing, slip out the octopus, rear back, and SPLAT! There she is at centre ice, with all the players poking at it as if it’s going to explode.” After Jerry died in a car accident, Pete took over the tradition. Pete described the best technique to Beddoes: “You grip the thing in the palm of your hand. You pick out your target. Then you rear back and heave it like you would a hand grenade. You got to keep your elbow stiff to get the best distance.” Pete Cusimano told Beddoes that he and his brother boiled the octopus beforehand to turn it bright red, but recent images and memorabilia show purple octopuses.

John Finley, former team doctor for the Detroit Red Wings, kept this Viceroy Rubber puck from the 1995 playoffs. The team did not “bring back the cup” that year, losing to the New Jersey Devils in the Stanley Cup Finals. Photo: Canadian Museum of History.

In the 1990s, Al Sobotka — building manager and ice keeper of Joe Louis Arena — began twirling the octopuses overhead as he fetched them from the ice. The Red Wings played their last game at Joe Louis Arena in April, but Sobotka recently told the Detroit Free Press that his ritual would continue. Over the years, the octopus became a symbol on Detroit Red Wings merchandise — like this puck from the 1995 playoffs — and a mascot for the team.

With so many stories to tell about the game, we had to make difficult choices and were not able to feature that particular puck in the Hockey exhibition. You can, however, see objects related to a notorious Canadian ritual inspired by Roger Neilson, a coach known for being an innovator. In a 1982 Stanley Cup semi-final, the Blackhawks beat the Canucks 4–1 in Chicago in a chippy match marked by fighting, both on and off the ice. Near the end of the game, Neilson, the Canucks head coach, put a trainer’s white towel on a hockey stick and waved it to protest what he believed was poor officiating. Some Canucks players did likewise. As a result, Neilson was ejected from the game, but Canucks fans loved his defiant act, bringing their own towels to waive at the next game, in Vancouver. Waving white towels during Canucks playoff home games is now a form of cheering, known as “Towel Power.”

Coach Roger Neilson was known for his innovations, and also for his wild neckties. This bobble-head doll shows “Rog,” with towel, and a colourful example. Doll on loan from the Peterborough & District Sports Hall of Fame. Photo: Canadian Museum of History.

In 1982, a Globe and Mail reporter described Nielson’s actions as embarrassing. He argued that the American press did not take the NHL seriously, and Nielson’s towel antics reinforced the idea that hockey wasn’t a big-league sport. The writer advised that: “The best thing would be for Neilson to issue an official public apology, and for everyone involved to forget about it.”

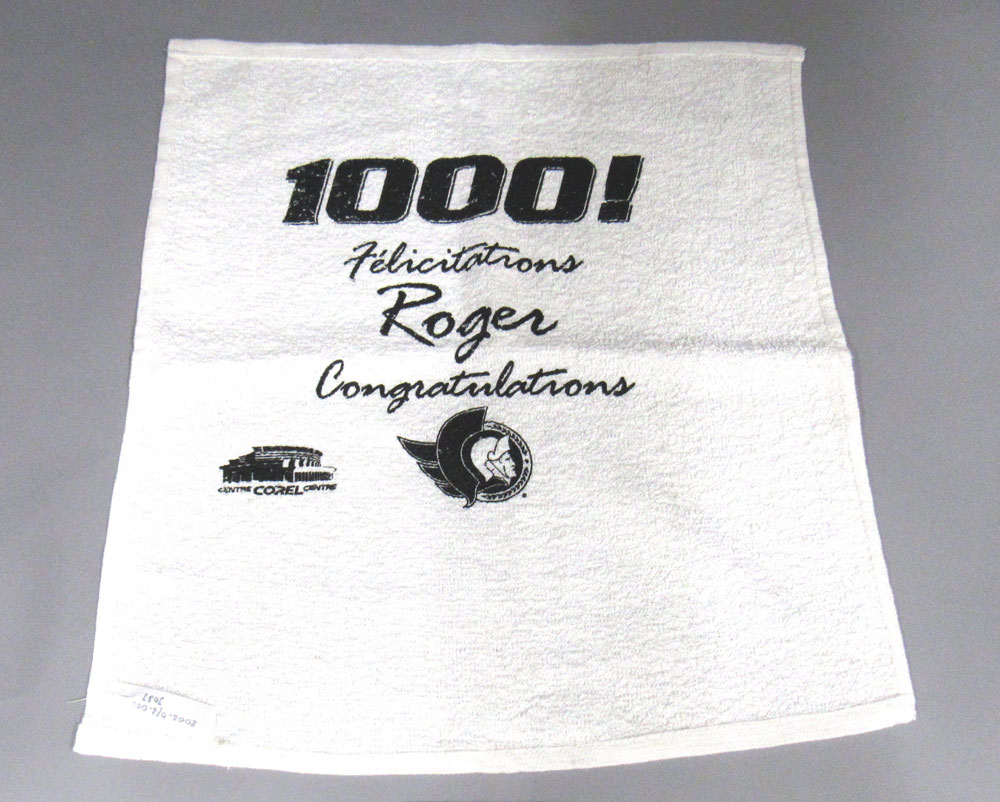

But Neilson’s act proved popular. In 2002, to mark Neilson’s 1,000th game in the NHL, the Ottawa Senators distributed white towels to attending fans, who are a big part of hockey history and culture. In fact, an entire section of the Hockey exhibition is devoted to fans, as they are an essential part of the game. You can see Neilson’s commemorative towel, as well as handmade items and memorabilia belonging to super-fans.

Roger Neilson inspired Vancouver’s towel-waving ritual. Neilson finished his career as assistant coach of the Ottawa Senators. The team made him interim head coach for the final two games of the 2002 NHL season, so he could reach the 1,000-game mark as a head coach. They issued these towels to mark the occasion. Neilson died in 2003. Towel on loan from the Peterborough & District Sports Hall of Fame. Photo: Canadian Museum of History.

What are your playoff rituals?