Museums and the Internet: Eight Years of Canadian Experience – Page 1

MUSEUMS AND THE INTERNET: EIGHT YEARS OF CANADIAN EXPERIENCE

Paper prepared by

Dr. Victor Rabinovitch, President and CEO,

Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation

with the assistance of Stephen Alsford, Web Site Manager

For “Museums, Media and Tourist Attractions”,

the 6th World Colloquium of the International Association of Museums of History

Lahti, Finland, May 2002

INTRODUCTION

The Internet provides a relatively new tool for a function that is not new: museum outreach. Museums have been engaged in public outreach for decades through initiatives such as travelling exhibitions, publications, educational programmes, and professional conferences. They have also reached out to potential audiences through a range of media, such as newspapers, magazines, radio, television, trade fairs and tourism expos. The Internet adds a new tool – along with some new challenges and opportunities – to these activities. I want to offer a Canadian perspective on these challenges and opportunities and examine how they may shape the future of museum activities.

Canada has the highest per capita use of the Internet in the world. The vast size of our country and the remoteness of many rural communities have forced our society to develop an innovative, effective and intensive national communications infrastructure, together with the industry and the public policies necessary to foster that infrastructure. The organization which I lead, the Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation (CMCC) 1, is our national museum of human history. It has the legislated mandate “to increase, throughout Canada and internationally, interest in, knowledge and critical understanding of … human cultural achievements and human behaviour“. Given the national and international scope of our audiences, and the limits to operating an institution physically rooted in a single location, it was natural that the CMCC become involved with the Internet, at an early stage in the emergence of the World Wide Web.

Museums and the Internet: Eight Years of Canadian Experience – Page 2

DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY AND MUSEUM AUTHENTICITY

Museums – and particularly history and ethnology museums – are inherently multimedia institutions. In attempting to convey to people an understanding of their heritage, museums should focus on their medium-of-specialization: historical objects. But they also use other communication media: historical illustrations and photos, sound recordings, film, environmental reconstructions, demonstrations, hands-on activities, costumed interpreters, and so on. These tools help to contextualize the artifacts, so that people can better appreciate the social role and significance of the objects and what they reveal about the past. Digital technologies make it possible to integrate visual and textual information and then broadly disseminate this to computer users, many of whom will be unlikely to visit the physical museum during their lifetimes. In this sense, we can look on new technology as an opportunity to extend our reach to new audiences, and to those who visit infrequently.

Will these virtual exhibitions supplant physical exhibitions? Our museum has over eighty virtual exhibitions on its Web site, and we receive very positive public reactions, but I do not see the Web replacing the “real thing.” Public feedback on our Web site indicates that an online presence draws attention to our physical installation and stimulates a desire to visit. The virtual exhibitions promote an appreciation of the rich knowledge resources that museums hold in trust. This information resource is made accessible for students and researchers wherever they may reside. But these positive aspects of the Web cannot disguise the fact that Internet technology is far from the point where it can create more than a pale imitation of the exhibition experience. It may never be that the emotional response to an encounter with the “real thing” can be evoked by a digital substitute. In most cases, the quality of a virtual exhibition seen on a video screen has not reached that of a glossy printed catalogue, which itself is only a reflection of the physical exhibition. Nor will it be easy to create an online version of the complex social interactions that take place during a family visit to a museum. I think we will find that Web sites tend to stimulate rather than replace museum visiting and, in particular, they can provide pre-visit information and orientation to help people prepare for a visit and get more out of it.

Does the use of flashy technology compromise museums by thrusting them into the arena of theme parks? Probably not. There are important differences that distinguish museums from theme parks, provided that the former are motivated primarily by educational goals, and the latter by commercial ones. This distinction will influence strategic decisions, including the ways interpretive technologies are used. The presentations and experiences museums offer are based on authentic historical objects and scholarly expertise. The two challenges for museums here are, first, to retain their authenticity and not be seduced into the use of technology for its own sake; and, second, to ensure the public remains aware of what differentiates a museum from other tourist attractions. These can be very real challenges as we compete for time and entrance fees from a public conditioned by television, commercial movies, and video games.

In terms of the relationship between museums and media, I want to stress that museums are inherently multimedia institutions, not just in their exhibitions, but also in what they collect. Heritage resides in physical objects or historic structures, and also in intangibles – processes, ideas, words, actions – which are often communicated through audiovisual media. The Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation (CMCC) has an extensive collection of such media – about 27,000 hours of audio and 8,000 hours of video – some dating back to the sound recordings made by field researchers in the early years of the twentieth century. One of our current challenges is to digitize these collections, storing the digital files, and making them easily accessible electronically. Thanks to streaming media formats, it is becoming more practicable to make audio and video accessible over the Internet. The CMCC Web site has made heavy use of this in one recent virtual exhibition on the subject of the musical traditions of different ethnic groups. We have also experimented with a live Webcast of an exhibition opening in which there were both speeches and cultural performances.

We should take a moment to look at the relationship between museums and journalistic media. There is value in a Web presence to provide the press and broadcasters with news and background information that can help promote the museum. The CMCC Web site has brought the museum to the attention of people not previously aware of it. We have also found that, as a ready-made and widely accessible source of information, the Web site has also attracted the attention of media researchers writing for magazines or preparing television documentaries.

It is essential not to visualize the Web within a single paradigm, such as it only being a carrier of virtual exhibitions. It is really a multi-purpose tool that can support many diverse operations of a museum. The Web is, in some ways, a multimedium. For example, we should consider how the Web might assist the merchandising of products, specifically as a vehicle that may eventually revolutionize the promotion, sale and distribution of certain types of museum products. Of course this will depend on an increase in consumer confidence in online shopping and other commercial transactions (such as banking). Such confidence is again appearing, despite the recent “dot com meltdown.”

There are three levels at which the Web can be used by museums in relation to merchandising:

- One is simply to promote their unique products, such as reproductions and publications, even if those products can only be purchased offline; the Web is a cheap advertising tool. At present, more people use the Web for window-shopping than for purchasing, but it is clear that information found online can influence many offline purchasing decisions.

- The second level is one of online retailing, by which I mean conducting an online transaction followed by offline product distribution. This can be an expensive museum initiative since the public demand for user-friendly purchasing procedures, efficient response time, and security of personal and financial information makes it advisable to have a well-designed, well-programmed, and properly staffed online shop. The issue here becomes whether it is cost-effective for individual museums to sell online, or whether to join online retailing consortia.

- The third level is where a product is both sold and distributed online. This is now widely done with software, already in digital form. We can expect to see digital information increasingly sold through online transactions, whether through a subscription or a micro-transaction model. Public willingness to pay for Web-based information is in proportion to its quality and relevance. Technologically, the challenge is to allow browsing through information products (as one would do in a bookstore), without giving away the information. Just as the MP3 phenomenon, in which pop music fans can download individual songs from the Internet instead of buying entire CDs, is threatening to overturn retail music sales, museums that publish may have to think outside the box, looking at different units of distribution in the digital age: chapters instead of books, individual images instead of exhibition catalogues.

Many museums have photo archives – some broad, some specialized – to document artifacts, or to show historical events. Such photos have been sought in the past for scholarly publications, magazine articles, etc. The change brought by the Web is that, by making the existence of these images more widely known, it is increasing the number of use requests. Photo researchers now use the Web as their first line of attack. The opportunity for museums to earn greater revenues from this source is evident. The challenge is to find the resources for photography, digitize the photographs, document the images, and make databases of those images and documentation accessible online. This is very demanding even for major museums such as my own institution. During the 1980s the CMCC was one of the pioneers in putting thousands of artifact images onto videodiscs. In the 1990s it switched to the purely digital medium of Photo CD. Between 1994 and 2000 about $2.5 million were invested in digitizing images and documenting them. We now have a collection of over 300,000 digital images. Our focus is to continue to add digitized records to our database and to develop the mechanisms for making these Internet-accessible.

Museums and the Internet: Eight Years of Canadian Experience – Page 3

ONLINE HERITAGE EXPANSION IN CANADA

Canadians have warmed to the Internet very quickly as another method of effective communications. Since the birth of our country, Canadian governments and the private sector have invested great resources into tying the country together, first with the railroad, then with satellite-based telecommunications, and today with broadband networks. With the exception of Korea, 2 the level of penetration of broadband access to the Internet is higher in Canada than anywhere else in the world, including the United States. A Household Internet Use Survey 3 by Statistics Canada showed that in 2000, 51% of Canadian households had at least one Internet user. A more recent survey 4 showed an increase in home Internet use between 2000 and 2001 of 18%.

Internet use trends and user demographics are broadly similar in Canada to those in the United States: 5

- Internet use has become a mainstream activity in the North American lifestyle; the perception among the middle class is that not to have Internet access from the home is to be disadvantaged.

- Growth in Internet use is particularly prominent among the younger generation, but people from all age groups are going online in growing numbers.

- The demographic of users is no longer oriented towards males, with high education, incomes, and technical training, but is now much closer to the general population demographic.

- Users, particularly as they gain experience and confidence, are going online more often and for longer sessions; it is likely that television watching is being reduced to spend more time online, by both adults and children.

- While about 80% of users still have telephone line Internet connections, the rate of high speed connection (cable and telephone) is growing slowly but surely.

- The primary reason for people to start using the Internet is no longer to have e-mail, but to have quick and convenient access to information; searching for information is by far the predominant use of the Web. 6

- There is a growing perception of the Internet as a huge combination of encyclopedia-research library-archives-newspaper. The Internet as a source of entertainment is not currently its central role.

The World Wide Web is viewed as an important source of information by the vast majority of its users, and there is a growing willingness to trust that information. This is ironic considering that the amount of human knowledge to be found on the Web is still small and fragmentary, if compared to the contents of a good public library. 7 The Web is becoming the most highly democratized publishing tool in human history; in fact, the backbone of the Web is sites created by private individuals on a voluntary basis. This growing trust in the Web as a research tool makes it that much more essential for institutions with a solid knowledge base, such as museums, to contribute substantially to the development of accurate online information.

Canadian museums did not hurry online when the Web was young. The first two Canadian museum Web sites, back in 1994, were of the Ontario Science Centre and the Canadian Museum of Civilization. Despite these pioneering examples, the largest and best-resourced museums (either in Canada or elsewhere) did not populate the Web quickly. A Web initiative was more determined by an enthusiastic employee, with some computer literacy and self-taught in Web page development, willing to take on the extra workload as a minimally funded experiment, with the indulgence of museum management. In fact, in larger institutions where questions of funding and programming are addressed through formal planning processes, there was typically a large delay in venturing online.

It is barely a decade that the Web has existed, but it has evolved considerably in its technologies and in needed design and programming skills. Yet this has not placed it beyond the reach of small museums with small budgets. Compared to conventional hard-copy methods for disseminating information, online publishing calls for less expensive equipment, fewer specialty skills, a much smaller team, and lower distribution costs. The Web continues to present museums of all sizes with an opportunity to promote themselves internationally, and to achieve some educational goals, in a cost-effective fashion.

Today it is safe to say, especially given the attention from governments at national to local levels, that the majority of Canada’s 2,300 museums or heritage institutions have some kind of Web presence. 8 The degree of investment does vary considerably from museum to museum; even institutions run with voluntary labour often find that one of their volunteers can put up a museum page on a personal Web site. The Web offers more of a level playing-field than most other marketing tools; a comparable geographic reach could not be achieved by a printed brochure. While small museums may not be able to hire professionals to produce glossy Web sites with interactive features, surveys show that Websurfers are most interested in the quality of information on a site, and the ability to find information quickly. Where small museums embarking on a Web project need to focus their attention is on care in planning the structure of a site and how to navigate through it, given that they may have to start small and develop the site over the course of several years.

Musée de la civilisation

http://www.mcq.org

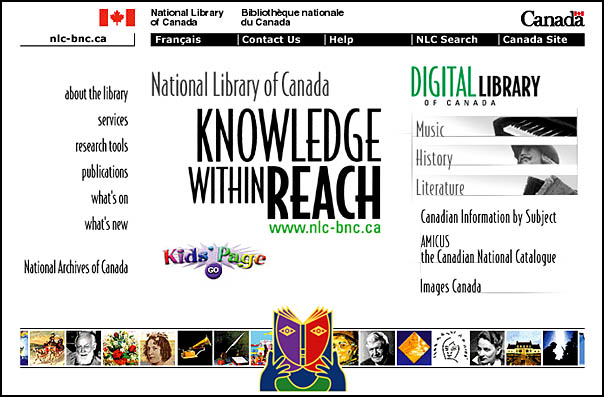

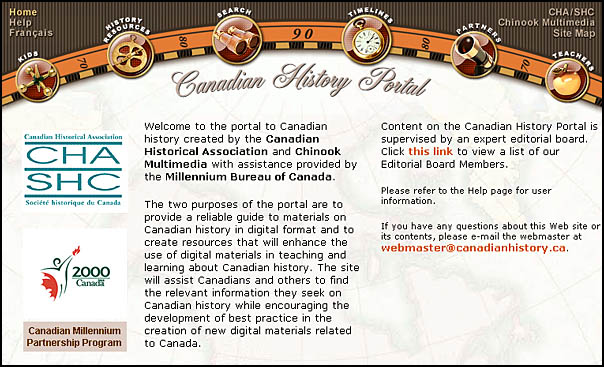

In Canada, the most substantial and professional-looking museum Web sites are those of provincial and national institutions. The Royal British Columbia Museum, the Royal Ontario Museum, the Musée de la Civilisation in Quebec, and the Nova Scotia Museum are just a few examples of human history museums with established and strong Web sites. 9 However, many of the sizable Web sites presenting Canada’s human heritage are not museum sites. They include other cultural institutions such as the National Library, which has created a “Digital Library of Canada” and the National Archives, which has (like the U.S. Library of Congress) created a collection of virtual exhibitions under the title “Canadian Memory” 10. Sites of government departments or agencies such as the Department of Veterans Affairs, Parks Canada, and the Department of Indian Affairs incorporate some authoritative knowledge resources. 11 A number of non-governmental associations are also presenting historical materials online, such as the Canadian Heritage Gallery, Canadian History Portal, Canada History, Histor!ca, and Early Canadiana Online. 12

National Library of Canada

http://www.collectionscanada.ca/index-e.html

Canadian History Portal – Created by the Canadian Historical Association and Chinook Multimedia Inc.

http://www.canadianhistory.ca/en/index.html

Some private sector projects have government financial support, because the federal government is an important player in developing the Internet in Canada. One of its earlier initiatives was SchoolNet, aimed at developing the infrastructure and teacher training so that almost all schools throughout Canada could take advantage of the educational dimension of the Web. SchoolNet also spawned a programme for decentralized content creation, through a funding programme, under the name Canada’s Digital Collections – probably the most extensive collection of online knowledge resources in Canada. 13

Canada’s Digital Collections

http://collections.ic.gc.ca

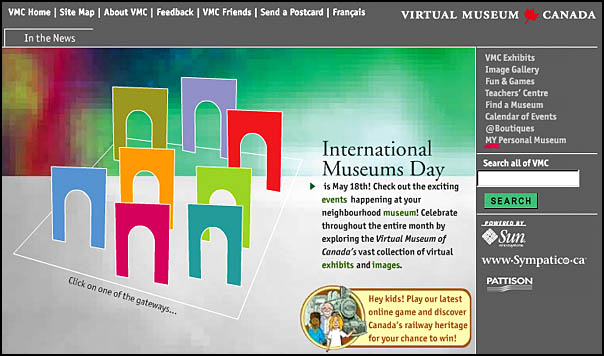

Home page of the Virtual Museum of Canada.

Courtesy of the Canadian Heritage Information Network, Department of Canadian Heritage.

http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/English/

More recently the emphasis on expanding online government services has resulted in funding support for other initiatives, such as the Virtual Museum of Canada 14 which assists the development of museum online content. The VMC is also a portal for decentralized virtual exhibitions (and for content to be found at the VMC site itself). The development of such portals 15 is the first phase of what has been predicted by some colleagues as the next stage of museum presence online: the meta-museum, taking an integrative approach to the distributed resources of individual museums. 16 Other examples of this trend are: Images Canada, 17 providing single-window access to the distributed collections of various government and non-government cultural institutions; a collaboration between federal cultural agencies to develop an online ticketing and reservations system to serve the needs of all partners; and Canada Place and Culture Canada, 18 the Department of Canadian Heritage’s portals to Canadian culture.

Culture Canada

http://www.culturecanada.gc.ca

Museums and the Internet: Eight Years of Canadian Experience – Page 4

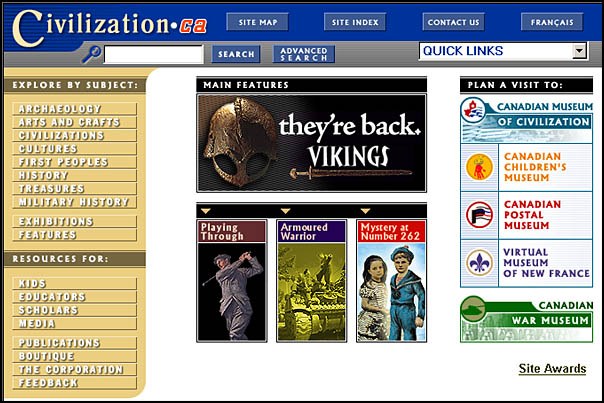

THE MAKING OF Civilization.ca

To my knowledge, no Canadian museum Web site is larger or older than that of my own institution, a site now branded as Civilization.ca. It started life in 1994 with just a few hundred screens of information, a single person responsible for it, and no dedicated budget. But, being in that pioneering wave of museums on the Web, it was able to attract an audience and, by continuous expansion of content, maintain and develop the audience. In its early weeks of existence, staff and management were pleased with statistics showing a couple of thousand page downloads each week. Little did they imagine that this visitation would increase dramatically over the rest of the decade. By 2001, the site received over 14 million requests for Web pages annually (a figure that translates to about 84 million “hits”, to use a term more commonly known).

Civilization.ca splash page

https://www.historymuseum.ca

Civilization.ca home page

https://www.historymuseum.ca/home

We are still trying to answer the question of precisely what these figures mean. There are many pitfalls in interpreting the basic sets of data collected by a Webserver. Museum managers are used to thinking in terms of numbers of visitors, but for various reasons it is difficult to identify a comparable concept in an online environment. The commonly reported statistic of “hits” 19 is not very meaningful. “Requests for pages”, also known as page accesses or page downloads, is somewhat more meaningful, and provides a better statistic for comparison to other Web sites. A third statistic is known as “user sessions” 20 which, although somewhat subjective, is about as close as we can come to something comparable to visits to the physical museum. We estimate that Civilization.ca hosts about 3 million sessions a year, compared to 1.5 million actual visitors to our physical installations. However, online user sessions are much shorter than physical visits; the average visit to our Web site lasts about 13 or 14 minutes, which is quite long in “Internet time”, but much less than the 4 hours which is typical for visitors to the physical museum.

From the statistics we analyse, complemented by qualitative data from public feedback, we have come to several conclusions about the profile of Civilization.ca‘s online visitors and their use of the site:

- In terms of demographics, our online visitors are very similar to the well-known profile of traditional museum visitors. 21

- A high percentage are those seeking education-related information (such as teachers, students, or parents).

- About 80% are interested in the knowledge resources of the site, while most of the remainder are looking for information to help them plan a visit to the physical site, or obtain access to museum products.

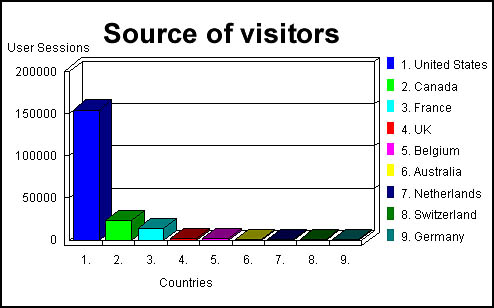

- The United States probably represents the largest source of online visitors (larger even than Canadians simply because of the large U.S. population). The third largest group is visitors from francophone countries, because our site is fully bilingual. 22

Online Visitors

Source: Web Trends

To illustrate what people value about the Civilization.ca site, let me cite (anonymously) several brief extracts from just a few of the messages we have received:

[from Canada] “In the past, for my Grade 10 Canadian History class I used your website… because I have not found anything that comes close in matching its detail, insightfulness and the rich primary sources…. It is truly an incredible resource for teachers to use to bring life and excitement to this topic.” [from the USA] “It’s a great thing to have such valuable information at my fingertips. I learned many things at your site. I will be back.” [from Canada] “It is wonderful to be able to access your site on the Internet. My family and I will enjoy expanding our knowledge of Canada and your Museum when we use the virtual tours!” [from France] “Bravo vraiment pour votre site que j’ai déjà consulté plusieurs fois. Il est delicieux…. Votre réalisation est suffisamment attrayante pour que j’envisage d’organiser, avec l’Association que je préside, un voyage au Canada pour visiter votre superbe exposition.” [from Hong Kong] “I am so impressed by your web. Much information to be found in this page. I think it is really very good.” [from Switzerland] “Cela fait longtemps que je surfe! Mais je n’avais encore jamais visité un site aussi formidable que le vôtre. Je cherchais des renseignements pour l’école car nous étudions l’Egypte et votre site est époustouflant! Facile à naviguer et quelle masse de renseignements! Je vais faire une super bonne note à mon exposé.” [from the Netherlands] “I was looking for some information for my daughter’s school project (she is 10 yr.) and what I found simply amazed me. It was so interesting and enjoyable that I spent hours to surf and read these material.” [from the UK] “The CMC site is the most exceptional and innovative museum website I have yet to see. Intellectual access to the collections and information was superior – fascinating, visually pleasing, and easy to use. As a museum curator in England, I have been investigating IT opportunities to increase the use of our collections. So far I have been dubious about the quality that can be achieved. Your site has changed my mind. As a matter of fact, I just meant to have a peek at your site and I’ve had to pull myself away after 45 minutes! I will be visiting again, and suggesting the site to teachers teaching Native Americans as part of England’s National Curriculum.” [from the USA] “FANTASTIC!!!!! Even with only a 14.4 modem I found the site very easy to access…. I cannot believe how wonderful your Pacific Coast Grand Hall tour is. Thank you so much for educating me in a way I would not have been able to experience without your web site.” [from Canada] “Your team has done a great job of building this site. I am pleased to see that you used rule #1: ‘Content is king’.”Of course, not all our feedback is so congratulatory! We receive criticism too, some constructive and some just downright insulting, but these have their uses, particularly in identifying some navigation problems. Consequently we gave special attention to navigation when the site underwent its first major redesign, culminating in a site relaunch in September 2001. 23

Canadian Postal Museum home page

https://www.historymuseum.ca/cpm/cpme.asp

Museums and the Internet: Eight Years of Canadian Experience – Page 5

THE MAKING OF Civilization.ca (continued)

Being able to navigate around Civilization.ca, or to find something on a specific topic, is a real challenge because we have such a large site. The site now comprises over 30,000 screens of static information, including dozens of virtual exhibitions, gallery tours, articles and monographs, press releases, brochureware, 24 list of publications, and much more. In addition, Civilization.ca gives access to various audiovisual presentations (which cannot be measured by numbers of screens or pages), plus our artifact collections database containing about 850,000 records (of which 46,000 are accompanied by artifact images), and the collection catalogue of our library and archives with 260,000 records. As you can imagine, it was necessary to build into the redesigned site a variety of navigation tools, including site index, site map, site search engine, and QuickLinks menus.

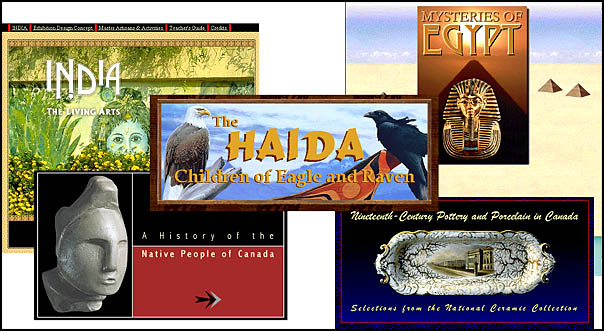

Virtual Exhibitions – Canadian Museum of Civilization

India, The Living Arts — The Haida: Children of Eagle and Raven — A History of the Native People of Canada — Nineteenth-Century Pottery and Porcelain in Canada — Mysteries of Egypt

Over its almost eight years of existence, the Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation (CMCC) Web site has seen experiments with a number of Web technologies and applications. In 1995 we opened an online shop, the Cyberboutique, and an online auction was held. 1996 saw the launch of one of the first “Virtual Museum” concepts on the Web, and the pilot of an electronic distance education programme called Cybermentor. In 1997 we added a second Virtual Museum, an international collaboration dedicated to the history of New France. 25 Also in 1997, we produced a QuickTime VR tour of the Canada Hall, 26 our largest permanent exhibition. In 1998, we introduced the site’s first VRML feature (a tour of Tutankhamun’s tomb), 27 an improved version of the Cyberboutique, 28 and the collections databases I already mentioned. In 1999 we experimented with a Webcast of an exhibition opening, 29 and in 2000 we introduced a micro-payment system to sell genealogical information for researching family history. 30

Cyberboutique

Canadian Museum of Civilization

Virtual Museum concept

Canadian Museum of Civilization

CyberMentor

Canadian Museum of Civilization

Virtual Museum of New France

Canadian Museum of Civilization

Collections Storage

Canadian Museum of Civilization

Iqqaipaa: Celebrating Inuit Art – Webcast

Canadian Museum of Civilization

The redesigned site launched last year introduced new sections for specific target audiences. For children, we created role-playing and adventure games of an educational character. 31 For educators we provided a portal to resources such as teachers’ guides, bibliographies, and some illustrated articles written specifically to support the school curriculum. 32 Another portal was provided for academics, giving access to more scholarly information, as well as adding a series of essays written by our curators. 33 Finally the media were given one-stop access to our press releases, media kits, and a password-protected archive of publication-quality digital images. 34 We also introduced a monthly electronic newsletter to which visitors can subscribe.

Mystery at Number 262

Canadian Children’s Museum

Armoured Warrior

Canadian War Museum

Most of this development has taken place with internal funding resources. Only in the last year have we had access to financial programmes through the Government On-Line initiative. This extra funding helps us to work on collaborative virtual exhibitions and on further digitization of collections.

Museums and the Internet: Eight Years of Canadian Experience – Page 6

WHAT IS VIRTUOUS AND VIRTUAL?

Given the breadth and length of Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation’s involvement with the World Wide Web, we have given thought to the question of what this all means for museums, and the relationship of the physical museum and the virtual museum.

Online consultation – architectural designs for the new Canadian War Museum.

Canadian War Museum

The Web site exists to support the museum’s mandate and its strategic goals, and thus reflects the museum’s programmes, services, and products. This does not mean only providing information about the physical installations, however. The fundamental purpose of the museum is to collect material history and to study the collections, thereby creating resources through which the public can learn more about Canada’s heritage. A Web site can fulfill that purpose in a different and complementary fashion compared to exhibitions, print publications, or other conventional outputs. While many of our online exhibitions are mirrors of physical exhibitions presented at the museum, others have been created exclusively for the Web site.

Any museum has limited physical space and limited “show time” for its exhibitions, but a Web site can continue to make the same information available long after an exhibition has been taken down. Its Web site becomes an archive and a long-term reference tool. Since most text and images used to produce a physical exhibition are in digitized formats, it requires relatively little added expense to produce a digital exhibition from the same material. Of course, not all subjects lend themselves to an online treatment, but many do.

The concept of a virtual museum may appear to undermine a fundamental value of museums, in terms of the focus on authentic artifacts that are the objective materials that mediate between the past and our understanding of that past. The concern with “real” versus “simulation” goes to the heart of the museum experience. Yet I think we will all admit that historical artifacts rarely speak clearly or directly. Museums use many aids to help artifacts speak: the Web is simply the latest addition to that toolbox. All historical interpretation involves hypothesis, so virtual museums are not artificial simulations so long as they are infused with accurate images of real historical objects, the authoritative knowledge of curators, and the professional commitment of museums for accuracy and authenticity.

The main challenge to museums from the Web stems from the nature of the Internet as a democratized vehicle for public communication. Any individual with a small amount of training can mount a Web site on some historical subject. While many such efforts are very good, others present biased, inexpert, or even lunatic-fringe interpretations. In the very early days of the Web, there was the virtual Louvre, an initiative of an individual that appeared to be the official Web site of the Louvre. We saw “virtual museums” created as class projects. We saw highly popular subjects, such as the origin of the Egyptian pyramids, given all sorts of unlikely explanations through personal Web sites. We saw extremist viewpoints proliferating on the Web. As a different type of challenge, we have seen the commercial sector present shallow accounts on various historical subjects, in order to entice the public to their sites, and to market products or services.

I believe it is incumbent on institutions dedicated to the dissemination of thorough historical accounts to ensure that the public is supplied with authoritative information of the highest quality. In computer jargon the term “virtual” means realistic, as opposed to real; that is, possessing the virtues of a thing without actually being it. But older uses of this and its related terms, such as virtue and virtuosity, have connotations of excellence and high standards, effectiveness and influence. In this regard I suggest that the virtual world of the Internet is not a landscape alien to museums; it is an extension of their natural environment.

Museums and the Internet: Eight Years of Canadian Experience – Page 7

NOTES

- The Corporation comprises two main museums with separate sites, the Canadian Museum of Civilization and the Canadian War Museum.

- Korea’s leading position is due in part to the high competition between broadband infrastructure providers, and also to the large proportion of Koreans who live in apartment buildings. For an analysis of international developments, see the report issued by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Committee for Information, Computer and Communications Policy, The Development of Broadband Access in OECD Countries, Paris: OECD, 2001.

- Reported in “Household Internet Use Survey”, The Daily, 26 July 2001; Statistics Canada Web site: http://www.statcan.ca/Daily/English/010726/d010726a.htm. The survey was conducted in January 2001.

- Reported by Guy Dixon, “More Canadians venture on-line at home”, Toronto Globe and Mail, 26 July 2001.

- Comparison has been made with the findings of the UCLA Center for Communication Policy, The UCLA Internet Report 2001: Surveying the Digital Future, Year Two, Los Angeles: University of California, 2001.

- No correlation has yet been found between Internet use and changes in children’s grades at school.

- Initiatives to scan entire library collections, while impressive, will ultimately founder because of difficulties with navigation, slow download times for scanned images of pages (nowhere near comparable with the efficiency and effectiveness of leafing through a book), and the inability to conduct full-text keyword searches on such images.

- The principal listing of Canadian museum Web sites, part of the WWW Virtual Library, is maintained by the Canadian Heritage Information Network at http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/English/Museum/Vlmp/vlmp.html but cannot be considered comprehensive, reflecting primarily those institutions with dedicated, as opposed to shared, sites. Statistics on the size of Canada’s museum community and its historical growth can be found on the Canadian Museums Association Web site: http://www.museums.ca/.

- Their sites can be found at (respectively): http://rbcm1.rbcm.gov.bc.ca/, http://www.rom.on.ca/, http://www.mcq.org/ and http://museum.gov.ns.ca/.

- Knowledge resources on these sites can be found at http://www.collectionscanada.ca/2/index-e.html and http://www.collectionscanada.ca/05/0599_e.html.

- Respectively: http://www.vac-acc.gc.ca/general/sub.cfm?source=history, http://www.parkscanada.gc.ca/lhn-nhs/index_e.asp, http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/pr/index_e.html.

- Their sites are found at: http://www.canadianheritage.org/, http://www.canadianhistory.ca/, http://www.canadahistory.com/, http://www.histori.ca/, http://www.canadiana.org/. A directory showing the extent of online coverage of Canada’s human history can be found on the Canadian Museum of Civilization Web site at: https://www.historymuseum.ca/orch/www00_e.html.

- At http://collections.ic.gc.ca/.

- Developed by the Canadian Heritage Information Network, long a leader in fostering the use of computer technology in museums. The VMC can be found at http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/.

- For example, the 24 Hour Museum in the UK (http://www.24hourmuseum.org.uk) and Australian Museums Online (http://amol.org.au/).

- George MacDonald and Stephen Alsford, “Toward the Meta-Museum,” pp. 267-278 in The Wired Museum, ed. K. Garmil-Jones, Washington: American Association of Museums, 1997.

- http://www.imagescanada.ca/

- http://www.culturecanada.gc.ca/ and http://canadaplace.gc.ca/

- Hits refers to a request made from a client computer to the server to deliver a specific file; most Web pages comprise multiple files, therefore this statistic provides a highly inflated portrayal of Web site use.

- User sessions represent a clustering of requests from the same user during a delimited time-frame, such as to suggest a “visit” marked by a commencement of activity and a conclusion of activity. However, defining the scope of a session is not an objective exercise and this makes comparability difficult.

- E.g. relatively high educational level and income, similar median age and range of occupations.

- This is federal government policy, but also a matter of pride in an institution whose aim is in part to show Canadians – anglophone and francophone – their shared heritage; Civilization.ca includes some content in other languages as well.

- The results can be seen at https://www.historymuseum.ca.

- That is, the kind of promotion or public information content traditionally issued through brochures or leaflets.

- http://www.mvnf.museedelhistoire.ca/

- QuickTime VR creates photographic panoramas of spaces, which can be stitched together to simulate a progression through a gallery; the tour can be found at https://www.historymuseum.ca/hist/qtvr/caqtvr1e.html.

- Virtual Reality Markup Language allows for a graphic representation of a space that can be explored by the computer user.

- https://www.historymuseum.ca/boutique/

- https://www.historymuseum.ca/aborig/iqqaipaa/theatre/iqqaip1e.html

- https://www.historymuseum.ca/vmnf/ancestors/

- Accessed through a Kids Page portal at https://www.historymuseum.ca/kids/kidse.asp.

- https://www.historymuseum.ca/educat/educate.html

- https://www.historymuseum.ca/academ/academe.html

- https://www.historymuseum.ca/media/mediae.asp