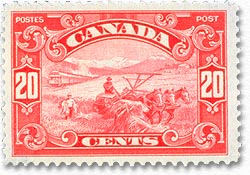

As a rule, however, the gaze of exclusion prevailed in the 19th century and workers were not visible on stamps issued by the Dominion of Canada during this period. The first sightings of workers on Canadian stamps can be dated from 1929 and 1930, when we can identify several workers who are engaged in bringing in the annual harvest of wheat. In the first of these (#157) we observe the preindustrial methods of harvesting that for several decades attracted thousands of hired hands from across the country to the wheatfields at harvest time; in the second image (#175) we are witnessing the arrival of mechanized harvest methods. Thus the two stamps stand at an important divide in the history of farm labour.15 No hint here of course, or later, of the collapse of agriculture or its human consequences during the 1930s. The most important observation is that in both cases the workers are subordinated to the main theme of the image, which is the harvest itself and, in part, the mechanization of production. The workers appear to be incidental to the larger story in these images.

Canada Scott 157

Stamp reproduced courtesy of Canada Post Corporation

|

|

|

Canada Scott 175

Stamp reproduced courtesy of Canada Post Corporation

|

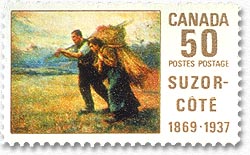

In at least two later stamps the gaze of inclusion is more direct, as agricultural labour is in the foreground. But in these cases the intentionality is not markedly different, for the official subject matter of the stamps is not the experience of work but the production of culture. The 1969 stamp (#492), reproduces a handsome early-20th-century portrait of farm labour that emphasizes the equal labours of men and women; the occasion was a tribute to the Québecois painter Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté. Similarly, a powerful 1979 stamp (#817) shows a pioneer farmer ploughing a field; this stamp was issued in honour of Frederick Philip Grove's novel Fruits of the Earth (1933).

Canada Scott 492

Stamp reproduced courtesy of Canada Post Corporation

|

|

The gaze of subordination is also apparent in the Bluenose stamp of 1929 (#158), which is a tribute to the famous fishing schooner that symbolized the maritime legacy of the east coast. The fishermen who sailed this vessel are barely visible in this image. However, by 1988 (#1228) the skipper at least had emerged from below and overshadowed the vessel; interestingly Angus Walters occupies a modest, and admittedly somewhat ambiguous, place in labour history for his part in helping to lead a campaign by fishermen and fishhandlers for higher prices in 1938; but this story remains relatively unknown to admirers of the Bluenose.16 Meanwhile, the gaze of inclusion had extended by 1951 to introduce the generic east coast fisherman (#302), here shown in romantic form on a rather rich one dollar stamp in his oilskins hauling in his nets. No evidence here of the new production methods and difficult choices facing the fishing communities at this stage in their history. The whole image is garlanded by the harvests of the sea, suggesting the inexhaustible bounty of the fishing resources, which are themselves the intended subject matter of the stamp.

|

Canada Scott 302

Stamp reproduced courtesy of Canada Post Corporation

|

In the narrative of resource exploitation and economic development, therefore, workers are often present but are usually subordinated to their work or to their machines. The contemporary fur trade is represented in a 1950 stamp (#301), showing a work scene at a snowbound encampment in the north woods; there was some objection at the time that the scene was not entirely realistic due to the enormous size of the skins.17 Wheat and oil, represented respectively by profiles of female and male figures, are featured in a 1955 stamp (#355), which was issued to mark the anniversaries of Saskatchewan and Alberta. A more naturalistic group of workers appear as members of a survey crew in a 1961 stamp (#391) promoting northern development. There is a tribute to the pulp and paper industry in 1956 (#362); here the worker is almost crowded out by the powerful image of the mill machinery. In the case of the textile industry, a 1953 stamp (#334) reveals no signs at all of human presence in the production process.

|