Words of Love: Valentines of the Victorian Era

If there is one day in the year when people most want to get mail, it would have to be February 14. Celebrating Valentine’s Day with messages of love is a tradition that dates back centuries. An early example is a valentine from 1477, housed at the British Library. In it, Margery Brews writes to her fiancé, John Paston, “Unto my right well-beloved Valentine John Paston, squire, be this bill delivered.”

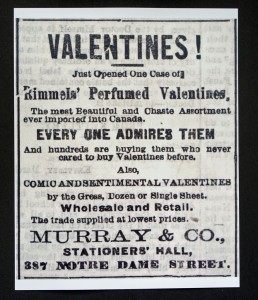

On this side of the Atlantic, interest in Valentine’s Day became apparent by the 1860s. Stationers advertised a vast array of valentines in newspapers such as The Gazette, The Globe and Mail and The Morning Chronicle. The popularity of valentines is no doubt what led the Post Office to make special mention of valentines in a new 1867 law providing for a uniform postal system for the entire new Dominion. “Valentines,” stated the law, “must be treated in all respects as ordinary letters, and the same care is to be taken both in their delivery and despatch.”

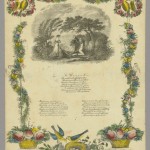

Valentine’s Day cards played an important role in courting rituals of the 19th century. Valentines served, in effect, as ambassadors. The pen became a substitute for a person’s physical presence. The first valentines were handmade and were used well before the advent of postage stamps and the use of envelopes. Valentines were written on a sheet of paper, which was then carefully folded and secured with a wafer of sealing wax. The name and address were written on the outside of the paper. These cards, dating from the 1840s, often featured an ink drawing or watercolour, along with a personal message.

Valentine’s Day cards were expected to represent the good taste and sincerity of the suitor. How many evenings must lovers have passed, seated at their writing desks, cutting out, pressing and assembling the decorative elements for their valentines. Once the design was completed to their satisfaction, they would take out their writing instruments to compose a sonnet or verse that would speak on their behalf.

- Valentine sent to Miss Henrietta Mann in 1857. There was no envelope; the letter itself was folded, and the name and address written on the outside. © Canadian Museum of History, 1983.192.23, IMG2008-0165-0034-Dm (1/2)

- Valentine sent to Miss Henrietta Mann in 1857. There was no envelope; the letter itself was folded, and the name and address written on the outside. © Canadian Museum of History, 1983.192.23, IMG2008-0165-0035-Dm (2/2)

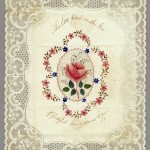

- Valentine from Joseph Addenbrooke, known for his paper lace, to which a handwritten poem has been added, around 1840. © Canadian Museum of History, 1983.192.13, IMG2008-0165-0021-Dm.

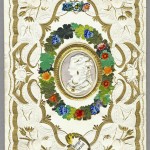

- Delicate and beautifully detailed valentine from Joseph Mansell, around 1840. © Canadian Museum of History, 1983.192.10.1, IMG2008-0165-0015-Dm.

- Valentine from Joseph Meek, with appliqués and a hand-painted watercolour. © Canadian Museum of History, 1983.192.8, IMG2008-0165-0012-Dm

To assist lovers lacking in inspiration, small manuals on the art of writing were readily available. These contained verses that could be transcribed onto a sheet of paper for people producing their own valentines. These booklets fell within a broader tradition of manuals related to letter writing and etiquette. Valentines manuals were popular during the 1830s and 1840s, but could still be found during the final decades of the 19th century. Despite their mediocre printing quality, the manuals were described in such grand terms as “elegant, fashionable, polite, original, sentimental, instructive” and so on.

© Canadian Museum of History, Valentine Verses or Lines of Truth, Love and Virtue, Reverend Richard Cobbold, 1827, no 2007.100, IMG2015-0024-0004-Dm.

Advertisement describing the range of valentines available from the stationer Murray & Co., in The Gazette, Montréal, March 4, 1875. Source: Library and Archives Canada / Montréal Gazette / March 4, 1875 / AMICUS 1412639

During the 1850s and 1860s, valentines with highly elaborate designs became popular. Valentines with handwritten verses gradually disappeared, to be replaced by manufactured cards. Advances in printing techniques made it possible to produce valentines that were nothing short of sumptuous. Cards might be decorated with entwined hearts, then enhanced with perfumed silk, shells and ribbons. The materials ranged from paper lace all the way to quilted satin, and even velvet. Some valentines were so elaborate that they had to be mailed in protective boxes. Merchants offered a nearly infinite array to please all tastes, all fancies and all pocketbooks. Highly extravagant and costly valentines also remained available, contributing to a redefinition of the standards of elegance and good taste.

Changes in the development and use of Valentine’s Day cards reflect the social and cultural preoccupations of a rapidly changing society. From personal messages written on folded sheets of paper to extravagant examples of the stationer’s art, valentines readily lent themselves to the fashions and tastes of the 19th century. The valentine, derived from a centuries-old European practice, was adapted and reinvented to secure an important place for itself in the socioeconomic traditions of the 19th century.

- Valentine and accompanying envelope, around 1860. © Canadian Museum of History, 2006.86.1; 7, IMG2008-0165-0210-Dm (2/2).

- Valentine and accompanying envelope, around 1860. © Canadian Museum of History, 2006.86.1; 7, IMG2008-0165-0221-Dm (1/2).

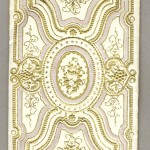

- Embossed paper valentine from Thomas de la Rue, around 1840. © Canadian Museum of History, 1983.192.6, IMG2008-0165-0009-Dm.

- Elaborate valentine, including appliqués and a perfumed centre section, around 1870. © Canadian Museum of History, 1983.192.83, IMG2008-0165-0116-Dm.

- Embossed paper valentine with verse printed on a small satin cushion, from around 1860. Valentines of this period sought to create an impression of volume through the layering of paper, appliqués and other materials. © Canadian Museum of History, 1983.192.66, IMG2008-0165-0088-Dm.

- St. Valentine’s Day (expectation, disappointment). Source: Library and Archives Canada / Canadian Illustrated News / February 12, 1870 / AMICUS 133120 / Page 16.

- Series of appliqués sold by stationers to create valentines. Quickly becoming popular, the appliqués were preserved in scrapbooks. © Canadian Museum of History, 2011.148; 150; 160, IMG2015-0024-0003-Dm.

- Valentine created for display, around 1900. © Canadian Museum of History, 2011.P0008.38, IMG2015-0024-0001-Dm

- Valentine created for display, around 1900. © Canadian Museum of History, 2011.P0008.38, IMG2015-0024-0002-Dm.