Preserving history, one page at a time

In 2014, the Canadian Museum of History acquired a handwritten copy of the lyrics to the abolitionist song “I’m on My Way to Canada.” Composed in 1852 by Joshua McCarter Simpson, an African-American composer and agent on the Underground Railroad, the song expresses a slave’s desire to flee the United States for Canada and its promise of freedom.

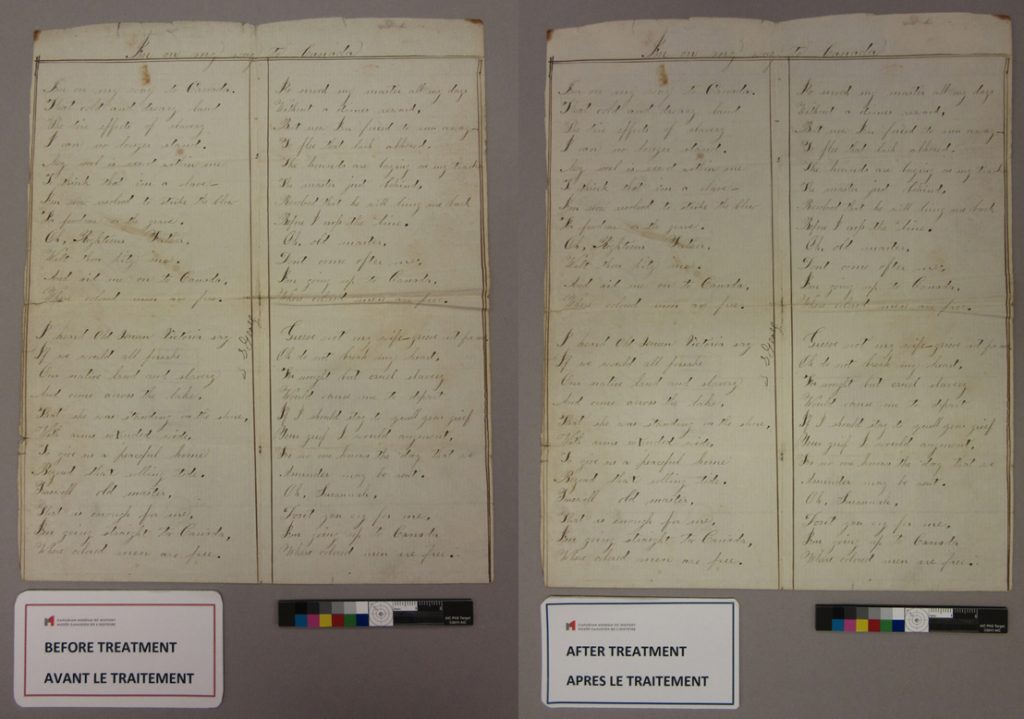

Fast-forward to 2017, and the Museum is busy preparing for the July opening of its Canadian History Hall, a 40,000 square foot gallery in which authentic artifacts will trace Canada’s history from the dawn of human habitation to the present day. The lyrics to “I’m on My Way to Canada” were chosen to help tell Canada’s story. But first, the document needed to be stabilized for display.

The main conservation goal was to stabilize the sheet’s splits, resulting from years of being folded in eighths. Gelatin and Japanese tissue were applied along the central, vertical crease where the paper was split.

The song is written on a single sheet of paper — not a large artifact, but when paper conservator Amanda Gould took a closer look, she discovered that it presented some significant challenges. Namely, having been folded in eighths for quite some time, the paper had split along its creases. Gould’s main goal was to stabilize those splits.

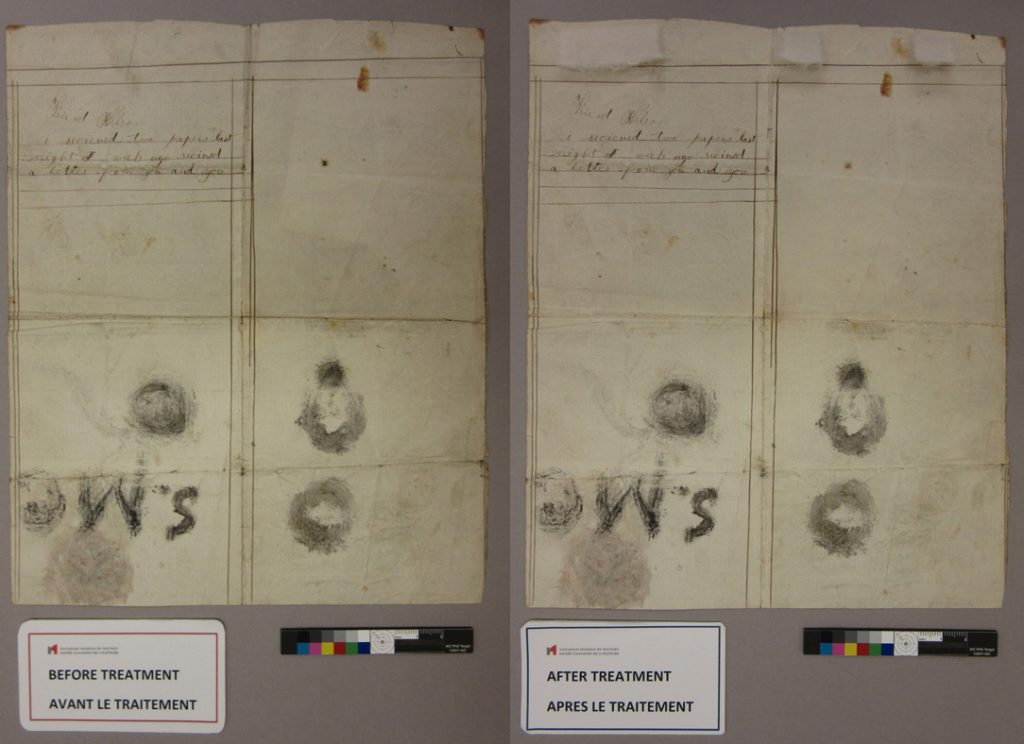

First, she had to consider what types of media were present on the artifact. In addition to the actual lyrics, the paper contained some doodles. A man’s face with a goatee, for example, can be seen on the back. These doodles were drawn in different kinds of ink, which tests identified as being water soluble. This meant that the conventional process of repairing tears with Japanese tissue and wheat starch paste had to be ruled out because it involved too much water.

Splits along the creases were stabilized as a result of the treatment. Though these images do not show a dramatic visible difference between before and after, the conservation done on the paper sheet will better preserve it for the future and will allow this authentic artifact to be displayed in the Canadian History Hall. Here, we see the front of the sheet.

Also complicating the process was the presence of iron gall ink. Widely used throughout history, this ink is a widespread conservation problem. Iron gall ink was made at home, mixed by individuals in a variety of ways, using a variety of ingredients. One ingredient, however, was always present: iron(II) sulfate. And it is iron(II) that poses the problem now, mainly because — simply put — it can be corrosive.

Luckily, conservators the world over have been working on solutions. Unfortunately for Gould, however, the most common application of these solutions uses water. She found herself in a Catch-22. She could not solve the problem of iron gall ink without destroying the doodles on the back of the document.

Splits along the creases were stabilized as a result of the treatment. Though these images do not show a dramatic visible difference between before and after, the conservation done on the paper sheet will better preserve it for the future and will allow this authentic artifact to be displayed in the Canadian History Hall. This image shows the back of the sheet.

Gould knew that if she wasn’t able to figure out how to stabilize it safely, the artifact would not be eligible for display. She spent hours thinking, researching and talking with colleagues, determined that this important piece of history would not be shut away from sight. Finally, she hit upon a solution. She would apply gelatin to Japanese tissue, resulting in a repair method that requires the use of only a minimal amount of moisture.* Research also shows that gelatin has a beneficial effect on iron gall ink.

In the end, the actual conservation process took only a fraction of the time that Gould spent coming up with a solution. But her efforts were worth it because when the Canadian History Hall opens on July 1, visitors will be able to see the original handwritten lyrics of a song highlighting Canada’s part in the struggle for freedom.

*E. Jacobi, B. Reissland, C. Phan Tan Luu, B. van Velzen and F. Ligterink, “Rendering the Invisible Visible,” Journal of Paper Conservation, 12, 2 (2011).