Laurier in Two Dimensions: Sir Wilfrid Laurier in the Canadian Museum of History’s Archival Collections

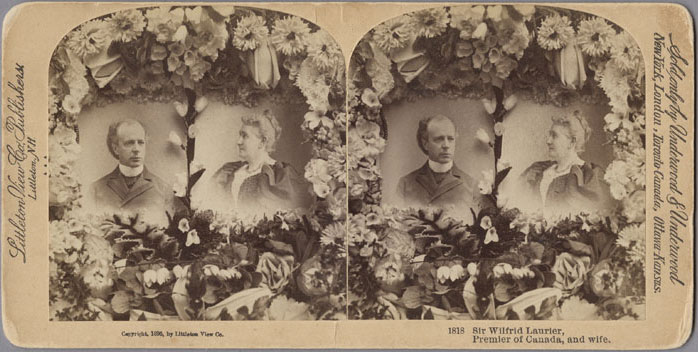

Stereograph depicting Laurier and his wife, 1896. A stereograph consists of two nearly identical images, glued onto rigid card stock. The image is then viewed through a binocular device called a stereoscope, which causes the eye to combine the two images, resulting in a three-dimensional effect. Canadian Museum of History, 2011-H0024, H-786, f6. Canadian Museum of History, IMG2014-0057-0001-Dm

Of all the figures who have emerged onto the Canadian political scene, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Leader of the federal Liberal Party from 1887 to 1919 and Prime Minister from 1896 to 1911, was perhaps the most popular. “Laurier had the gift of being loved,” noted former Liberal minister, Charles Gavan (“Chubby”) Power. Like certain rare political figures — such as Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy in the United States — Laurier was able to transcend party lines, attaining the status of a national icon long after details of his political exploits were forgotten.

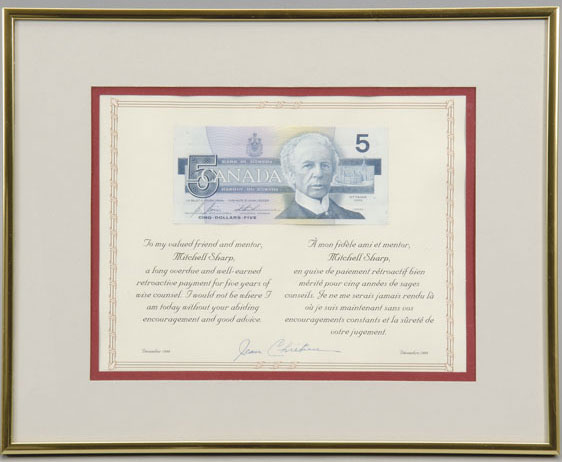

This affection was prevalent among Laurier’s Liberal followers, of course, but could also be found in his political opponents: nationalist Henri Bourassa and his supporters (although they still accused him of being “a sell-out”) and, at the other end of the spectrum, pro-British imperialists (who still found him, by contrast, insufficiently loyal to the Crown). Even when they did not approve of his actions, people could not bring themselves to hate him. Laurier remained in high regard long after his death in 1919, and “Laurierism” extended far beyond the political milieu. Today, villages and universities are named after Laurier, and his likeness can be found on everything from cigar boxes to marble statues to our five-dollar bill.

How to explain Laurier’s aura? He represented — and continues to represent — an idealized Canada. He was bilingual and was seen as unifying, conciliatory and pragmatic. In addition, he stayed true to his French-Canadian origins, he took pleasure in the company of English Canadians, and he respected new Canadians. Laurier expressed an abiding love for all regions of the country. Finally, he was elegant, refined and eloquent — which lent prestige to his fellow citizens — all while remaining charming, jovial and approachable. He was also cultured and urbane.

For Laurier, politics meant more than a minor struggle to win a county here and there with promises of a road or a post office. Although he was well aware that “elections are not won by prayers,” as his ally Joseph-Israël Tarte once said, he preferred to aim higher. The speeches in which he described his concept of liberalism, for example, or those in which he paid homage to both France and the British Empire, demonstrated that Laurier was a man of ideas — and that, for him, political engagement was a matter of values and principles.

A year ago, we published an online gallery of artifacts from the Canadian Museum of History depicting Sir Wilfrid Laurier. Here in this post, we feature a sampling of “Laurierism” from the Museum’s document collections (letters, photographs, sheet music, postage and more).

- Patriotic poster commemorating the tenth anniversary of the death of Laurier, published in the newspaper La Presse, February 16, 1929. The poster features a reproduction of the painting Le deuil de la patrie (The Motherland Mourns) by Georges Delfosse. Canadian Museum of History, 2011.21.685. Gift of the Hon. Serge Joyal, P.C. IMG2014-0141-0008-Dm

- Framed five-dollar bill featuring Laurier, presented by Prime Minister Jean Chrétien to his advisor Mitchell Sharp to thank him for five years of volunteer service to the Cabinet, December 1999. Canadian Museum of History, 2005.32.67. Gift of Jeanne d’Arc Labrecque Sharp. IMG2008-0060-0085-Dm

- Le libéralisme politique [Political Liberalism] — the classic lecture given by Laurier on June 26, 1877, reissued in 1941. CMH, Library, GEN JL 197 L5 L38 1941. Photo: Xavier Gélinas, PB100739

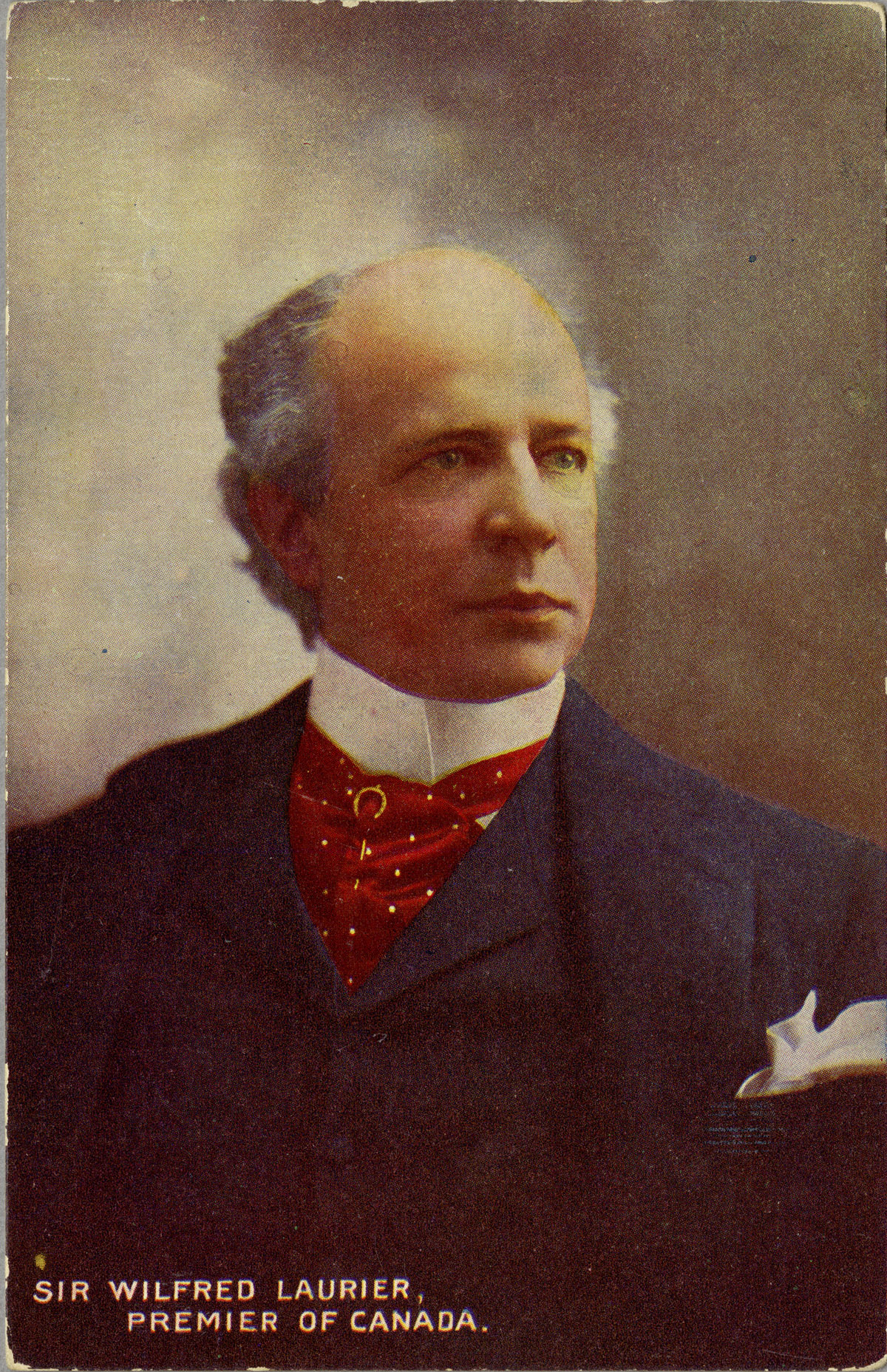

- Hand-coloured postcard depicting Laurier, undated. Canadian Museum of History, 2012-H0040.75.001. Gift of the Hon. Serge Joyal, C.P. IMG2016-0101-0001-Dm

- Postcard: “The Old Pilot ‒ Canada ‒ The New Nation,” undated. Canadian Museum of History, 2012-H0040.78. Gift of the Hon. Serge Joyal, C.P.

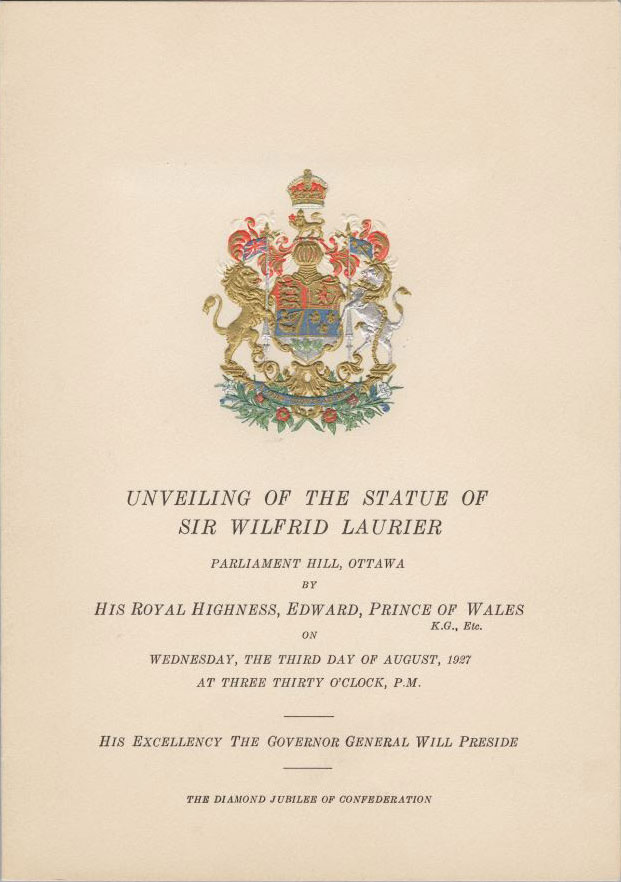

- Souvenir program for the unveiling of the monument to Sir Wilfrid Laurier on Parliament Hill, August 3, 1927. Canadian Museum of History, 2012-H0040.101.1. Gift of the Hon. Serge Joyal, C.P.

- The Heritage of Canada: The Most Celebrated Speeches of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, 33-rpm RCA Victor recording, 1968. Produced by journalists Laurier Lapierre and Patrick Watson of the CBC. Canadian Museum of History, ACQ 2012.17, temporary no. 342.3. Gift of the Hon. Serge Joyal, C.P. Photo: Xavier Gélinas, 342.3

- Letter from Laurier to painter Georges Delfosse, December 3, 1903. Canadian Museum of History, 2011.21.486. Gift of the Hon. Serge Joyal, C.P. IMG2012-0294-0029-Dm

- Promotional pamphlet: Canada : Laurier et Prospérité [Canada: Laurier and Prosperity], 1903 — an early example of political marketing. Canadian Museum of History, Library, ACQ 2012.17, temporary no. 174.3. Gift of the Hon. Serge Joyal, C.P. Photo: Xavier Gélinas, 174.3

- Sheet music for the song, “Restons toujours braves, Canadiens français” [French Canadians, Let Us Always Be Brave], 1913. Canadian Museum of History, ACQ 2015.18, temporary no. 82. Gift of Grant Harper. Photo: Xavier Gélinas, 006

- Black and white photograph of Laurier, inscribed to his friend “Charlie,” undated. Canadian Museum of History, 2014-H0010, H-412. Gift of Juliana Ovens.

- Photograph of Laurier taken around 1885, shortly before he became Leader of the Liberal Party of Canada. Canadian Museum of History, 2012-H0040.93. Gift of the Hon. Serge Joyal, C.P.

- Sheet of 100 postage stamps depicting Laurier, 1973. Designer: David Annesley. Canadian Museum of History, Scott 587, IRN 1332913. Photo: Xavier Gélinas, PB040737

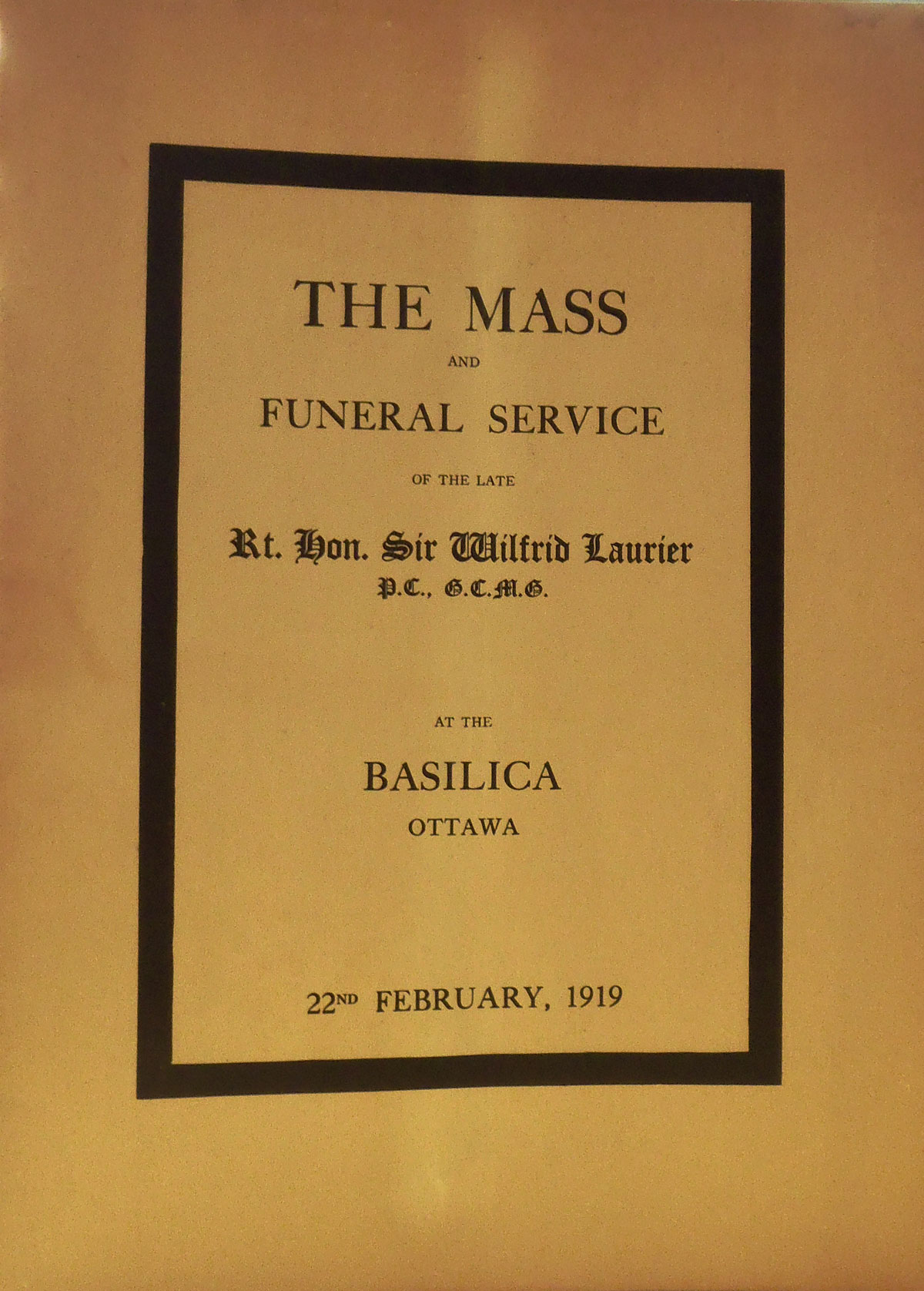

- Program for Laurier’s funeral mass at the Basilica in Ottawa, February 22, 1919. Canadian Museum of History, Rare Books, FC 551 L3 M37 1919. Photo: Xavier Gélinas, PB140740

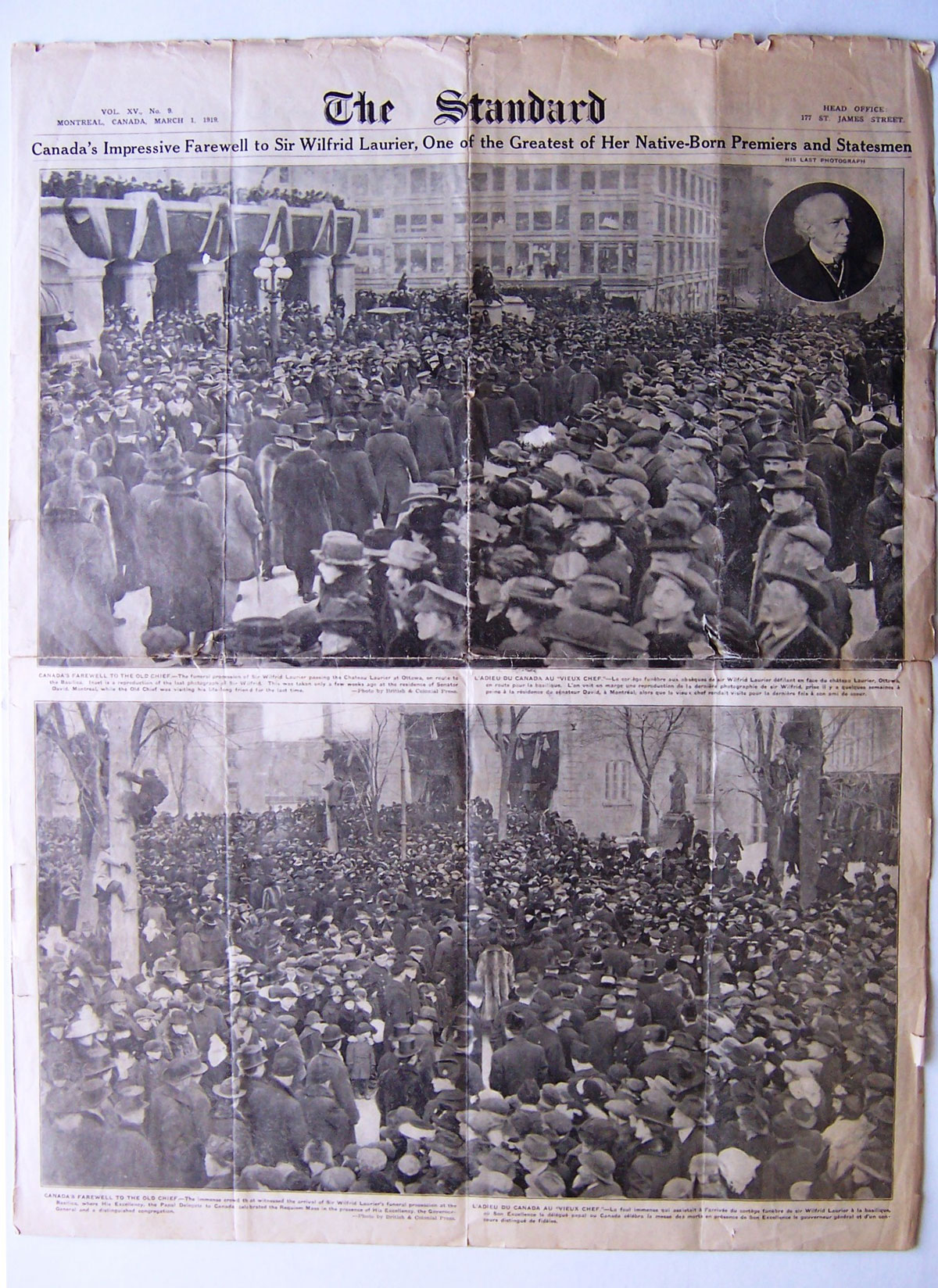

- Special edition of The Standard, March 1, 1919, featuring photographs from Laurier’s funeral. Canadian Museum of History, ACQ 2012.17, temporary no. 217.2r. Gift of the Hon. Serge Joyal, C.P. Photo: Xavier Gélinas, 217.2r

![Le libéralisme politique [Political Liberalism] — the classic lecture given by Laurier on June 26, 1877, reissued in 1941. CMH, Library, GEN JL 197 L5 L38 1941. Photo: Xavier Gélinas, PB100739](https://www.historymuseum.ca/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/brochure-Libéralisme-politique-PB100739-1.jpg)

![Promotional pamphlet: Canada : Laurier et Prospérité [Canada: Laurier and Prosperity], 1903 — an early example of political marketing. Canadian Museum of History, Library, ACQ 2012.17, temporary no. 174.3. Gift of Serge Joyal. Photo: Xavier Gélinas, 174.3](https://www.historymuseum.ca/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Livret-Canada-Laurier-prosp_web-1.jpg)

![Sheet music for the song, “Restons toujours braves, Canadiens français” [French Canadians, Let Us Always Be Brave], 1913. Canadian Museum of History, ACQ 2015.18, temporary no. 82. Gift of Grant Harper. Photo: Xavier Gélinas, 006](https://www.historymuseum.ca/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/partition-chanson-006_web-1.jpg)