Expanding on The Empress Part 2: The Pilots of Point-au-Père

Taking on the Pilot, near Rimouski, Québec, early 20th century. Canadian Museum of History, Phlippe Beaudry Collection, 2012-H0018.20

The sinking of the Empress of Ireland in May 1914 was a powerful demonstration of the hazards of navigating the St. Lawrence River. It served as a reminder that knowledgeable hands were needed behind the helm as ships entered and exited from what was then Canada’s busiest waterway.

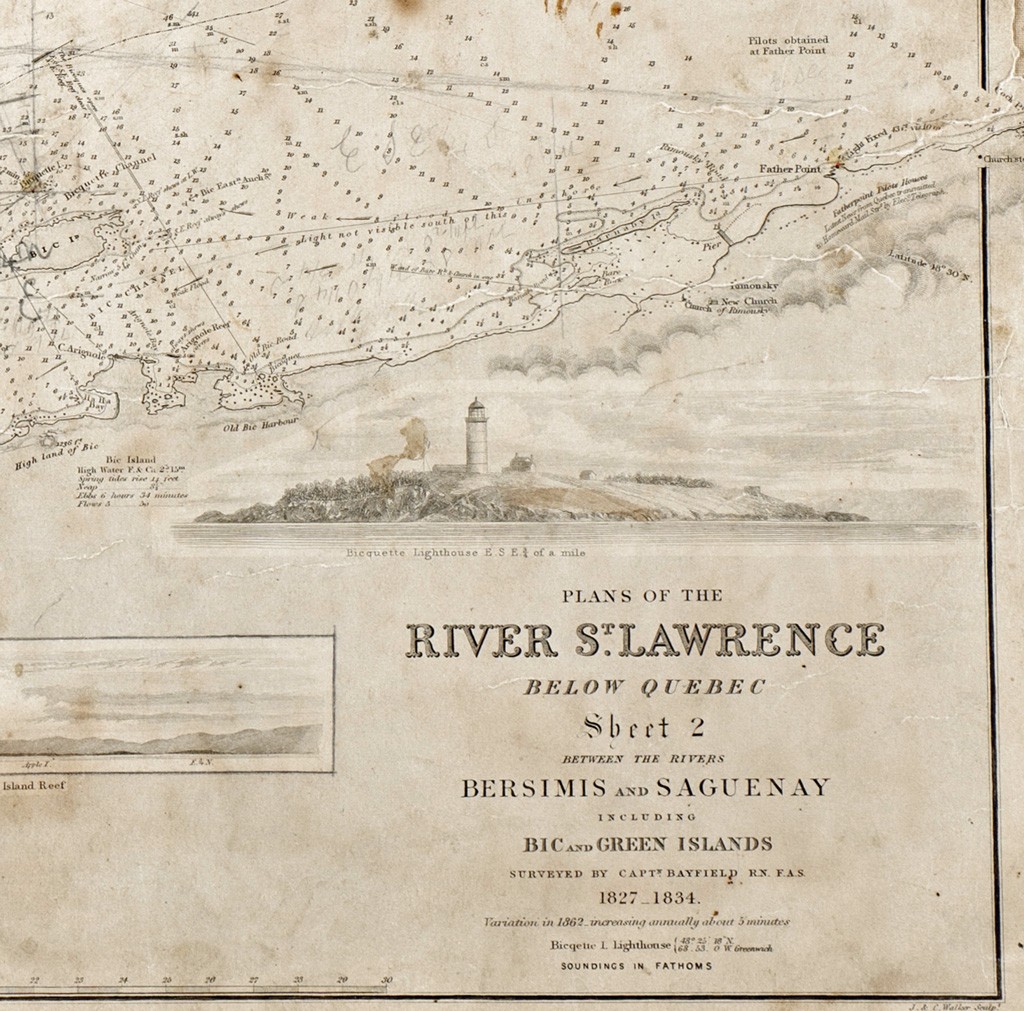

By the turn of the 20th century, there were about 70 pilots steering ships along the St. Lawrence, below Québec City. Their task was complicated by the vagaries of weather, climate and fog, and the very nature of the river itself, which narrows progressively as you move upstream. Mariners also had to beware of the series of islands out in the channel from l’Ile Verte and l’Ile au Lièvres to l’Ile d’Orléans. During the 1913 navigation season, three pilots were suspended for mishaps that involved the ships they guided, including the CPR steamer, S.S. Lake Manitoba.

With the increasing number of accidents, likely caused by the rise in traffic, the pilots came under fire in the press and throughout shipping and business circles. The Montréal Board of Trade felt that the incompetency of the river pilots was the cause of the mounting number of mishaps on the St Lawrence. They pointed to the rise in marine insurance premiums. A Royal Commission, convened in 1913, called for the abolition of the Corporation of Pilots and the tour-de-rôle system (where pilots took charge of vessels in turns and pooled their wages), a reduction in the number of pilots and the immediate dismissal of the superintendent of the Montréal channel pilots, a man viewed as unfit for the job. The Commission pointedly remarked that the pilot office in Québec City was upstairs from a bar “having a door leading directly into that place” and urged that the office be closed down immediately.

The pilots were unwilling to accept recommendations from an investigative body that they viewed as a puppet of the Shipping Federation. They felt that they were being unfairly blamed for the increase in shipping accidents and said so in their minority report to the Royal Commission. “Everyone has in mind the mishap of the S.S. Helvetia, sunk by the Empress of Britain,” they stated. “Who does not remember the S.S. Titanic? These vessels were not handled by pilots when they met their sad fate.” Moreover, they felt that the Department of Marine and Fisheries, which had recently taken over the administration of the pilots, was treating them with disrespect, forcing them to take a navigation test a day before the opening of season in 1906 and asking them to pass exams in English when most of them were French-speaking. The pilots took particular exception to a comment from one of the Commission members that their job was easy; so easy they could smoke their pipe as they headed for work. They responded by saying, “We would like to have him smoking with us when we are tossed in the S.S. Eureka at Father Point during stormy weather. We think he would soon find our tobacco too strong for him.”

Pilots worked out of Pointe-au-Père and Québec City, attaching themselves to the local society for the duration of the navigation season. Some worked on the tour-de-rôle basis; others were attached to a shipping line such as the CPR or the Allan Line. The Dominion Coal Company used nine regular pilots on its vessels. In some instances, outbound colliers did not even bother to leave off their pilots at Pointe-au-Père. These pilots remained aboard until the ships reached their destination, usually Sydney, Nova Scotia, the main harbour for shipping out Cape Breton coal. Charles Clavet, a pilot with 25 years of experience, lost his life when the ship he was on, the S.S. Bridgeport, went down shortly after leaving Sydney harbour in November 1913. Clavet should not have been aboard; he should have disembarked at Pointe-au-Père.

When the pilot station was moved to Pointe-au-Père in 1905, it was subsequently outfitted with a new lighthouse, pier, wireless telegraphy station, rescue equipment and a machine-powered fog horn. The old McWilliams schooner was no longer used. A new pilot boat was pressed into service. Built in Glasgow in 1893, the S.S. Eureka was a converted coal-powered tug, 94 feet (almost 30 metres) in length. The Eureka was not the best of vessels when the weather was rough. The Pilots recommended acquiring a larger, more seaworthy vessel, equipped with wireless radio telegraphy and searchlights for night work, and with room enough to clothe and feed pilots so they would not have to pay room and board ashore.

Map of the St. Lawrence shoreline showing the old Bic Harbour in the lower left and Pointe-au-Père (Father Point) in the top right corner. Photo by Steven Darby, Canadian Museum of History, after an original from the collections of the Musée maritime du Québec.

On board the Eureka was a man no doubt familiar to the pilots: Captain Jean-Baptiste Bélanger, a native of L’Anse-à-Gilles, near L’Islet-sur-Mer, and an experienced navigator. It was Bélanger who was first on the scene after the Empress of Ireland went down early in the morning of May 29, 1914, his lifeboats lowered and at the ready. He saved dozens of lives that morning. Bélanger eventually testified at the Commission of Inquiry following the Empress disaster. The story of his exploits was handed down through his family for generations.

Captain Bélanger may or may not have seen John McWilliams’s old pilot schooner, but he certainly could have heard about it from the older pilots that he carried to and from work. Our model does conjure up a vision of ships at sea, “the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song…with the white clouds flying …the sea gulls crying” (John Masefield) and a host of memories; memories that speak of a time when ships sailed up and down the St. Lawrence River, as they still do, bearing passengers, crew, cargo — and always a pilot and a pocket full of dreams.