Earth Day Lessons from a Soapbox (or Three)

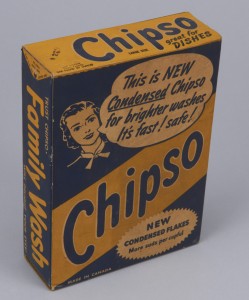

April 22 is Earth Day, celebrated annually since 1970 to encourage ecological awareness and action. Environmental activists and concerned citizens will mark the occasion, and so will advertisers. Demand for environmentally friendly consumer goods has dramatically increased in recent years, and “green marketing” now sells everything from light bulbs to automobiles — and soap. A small collection of vintage laundry-detergent boxes at the Canadian Museum of History illustrates the emergence of green marketing in Canada in the early 1970s. Then, as now, consumer preferences and government regulations influenced how producers advertised their wares. These boxes also underline how the decisions made by curators years ago have helped to make our collection relevant today. In the years of prosperity that followed the Second World War, automatic washing machines became common in Canadian households, as did synthetic detergents. These detergents used chemicals to produce suds. In the heated competition between detergent makers, producing more suds was a way of distinguishing a product from its competitors. Makers of “Chipso,” for example, proudly proclaimed that their “new condensed flakes” produced “more suds per cupful.”

Chipso was the first laundry detergent specifically designed for automatic washing machines and dishwashers. This box, likely from the 1940s, proudly proclaimed that the “new condensed flakes” produced “more suds per cupful.” Canadian Museum of History, D-13436, IMG2015-0022-0074-Dm.

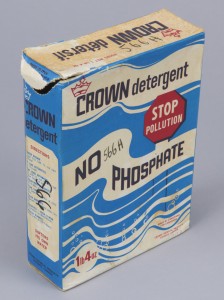

However, the compounds that produced suds in the washing machine also produced unsightly foam in lakes and rivers. Moreover, phosphate “builders,” which improved the detergent’s performance by softening the water, fertilized toxic algal blooms. This threatened drinking-water supplies and commercial fisheries. Manufacturers resisted regulation, but citizens demanded change. In 1970, the federal government limited the phosphate content of detergents. The fledgling, media-savvy Canadian environmental movement claimed a victory. Detergent makers quickly turned phosphate restrictions into a marketing opportunity. Where just a decade earlier soapboxes had promised superior suds, environmental responsibility became the new key selling point. A box of Crown detergent urged consumers to “stop pollution” by switching to Crown’s “no phosphate” formula.

Following the federal government’s decision in 1970 to limit the phosphate content of detergents, detergent makers began to use environmental responsibility as a key selling point. This box of Crown detergent from the early 1970s urged consumers to “stop pollution” by switching to Crown’s “no phosphate” formula. Canadian Museum of History, T-1319, IMG2015-0022-0098-Dm.

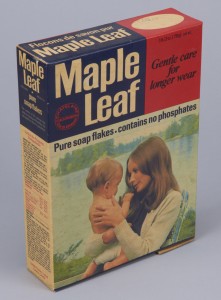

Maple Leaf detergent made a similar promise, using imagery that is now common in environmental marketing. Their soap flakes were not only phosphate-free, they also offered “gentle care,” symbolized by a young mother and baby. Emphasizing the ecological benefits of the product, the label also featured a pristine lake, free of the unsightly foam and toxic algae that an earlier generation of detergents had caused.

Maple Leaf detergent also employed techniques that are now common in environmental marketing. This box of detergent produced in the early 1970s promotes phosphate-free soap flakes and offers “gentle care,” symbolized by a young mother and baby in front of a pristine lake. Canadian Museum of History, T-1307, IMG2015-0022-0096-Dm.

Advertising strategies change to reflect consumers’ evolving values; this is just one of the stories told by the Museum’s extensive commercial-packaging collection. The boxes also tell the story of collecting contemporary historical artifacts. The Chipso box came to us from the private collection of David Chavel, a professor at the Ontario College of Art and Design University with an interest in packaging design. We acquired the Crown and Maple Leaf boxes through an innovative collections project called “Future History.” Between 1971 and 1976, project participants collected examples of consumer goods that were then readily available, anticipating that one day these items would become historically significant. Could the curators responsible for the Future History project have foreseen the growth of environmental marketing in the 40 years since they acquired these boxes?